Оver many centuries, humanity has used wood — a simple, convenient material — to manufacture various objects, both for pragmatic and decorative purposes.

In the distant past, natural, often impassable lands, densely covered the island: beautiful pine and cedar forests, as well as oak and nut groves, have brought fame to Cyprus since the times of the Antiquity (there are well-known references form the antique scholar Eratosthenes in 3 B.C).

Thus, in bygone eras, this abundance (along with copper deposits) has attracted numerous neighbouring nations to the island. Various tree species (especially, pine, nut, cypress etc.) were widely used for constructing fishing boats and large merchant ships, in addition to manufacturing agricultural equipment and household appliances. Aside from this, wood was used to build many things or used as a source of energy.

A little later, the island locals began using wood to create statues of gods, figures of men and animals and of course, furniture. Some well-known chair models with carved legs, which are still used in our time, belong to the Hellenistic era.

Incidentally, it’s worth noting that wood carving in the territory of Ancient Rus [1] also began its development in the distant past — as early as 5 B.C.

Slavs attributed the magical power of a talisman to wooden items either in the shape of an animal or with the image of one; however, the wooden idol was considered the main guardian which protected each village from bandits and other misfortunes. Villagers would cut into a piece of wood 52 times (the number of weeks in a year) and then hoist it onto a pillar.

The medieval age is acknowledged as the heyday of wood carving in European countries, specifically from the 11th-13th century, when places of worship in Northern Europe were decorated with complex carvings combined with Celtic elements and Christian symbols.

In the Renaissance age [2] (more precisely, the 15th century) the art of woodcutting appeared — printing an image (an etching) onto a wooden block.

Let’s get back to Cyprus…

Cypriot craftsmen have long been able to print images onto wood, which depict their surrounding environment (animals, birds and plants). The symbolism of decorative patterns, alongside geometric motifs and shapes, has made for some astounding compositions.

Birds, symbolising love; wolves and lions, embodying strength and power; the Holy Cross, standing for the life cycle and Christianity; and angels, representative of protectors and patrons — these were the main figures created by the island’s master wood carvers.

In the mid 19th century, Lapithos (also once known as Lambus, Imeroessa and Lapithia — see here for more details), whose history spans over centuries, became a significant centre for the carving business in Cyprus. Its craftsmen have since been renowned for their works, finesse and unique flair for crafting beautiful items.

Interestingly, Lapithos was even mentioned by Strabo (64/63-23 B.C), an ancient Greek historian and geographer, who called it “a construction of the Laconians and Praxandros” [3]; Heraclitus of Ephesus (544-483 B.C), another ancient Greek and philosopher, deemed this place to be “imeroessa” (i.e. passion-arousing).

In the interiors of local mansions and ordinary housing owned by affluent villagers, as well as those with an average income, there was an excess of wooden objects expertly covered in carvings: cupboards, doorposts and door panels, as well as chairs, tables, staircases, book and crockery shelves, balcony cages and other decorative constructs, which were typically etched with various flowers, trees, animals, birds (doves) and grapes.

Chests for storing linen and a woman’s dowry — a basic element of traditional furnishing — are still produced to this day in several places on the island.

The set out of a local church interior consisted of a carved iconostasis, a lectern, bishops’ altars and a two-headed eagle, all of which were crafted with etched images of climbing vines, angels and other Christian symbols.

Calabrian pine, cypress, nut and sycamore were the main materials used by local carvers.

In addition, in the past, some tree species (such as sycamore) were imported from the southern coast of Asia Minor, approximately 200 kilometres from the island.

Carpenters were directly involved in manufacturing agricultural equipment and utensils, as well as instruments for construction and other purposes: ploughs, wheelchairs, spindles, handles and wooden shovels for sifting wheat. They also carved wooden panels for finishings to floors and ceilings; window shutters and breadboards.

Fine quality chairs, the seats of which were woven from special straw with a beautiful finish, were manufactured on lathes with various decor etched into them.

You can see samples, such as a late 19th-century chest, in the collection of the The Cyprus Folk Art Museum in Nicosia (the exhibit of the Old Archbishop’s Palace).

The unique combination of etching images into carved chests, etageres, sideboards and crockery shelves, predominantly developed and flourished in Akanthou [4], beginning in the mid 19th century. The best carvers, from all the island’s villages, were considered to have lived here… but there’s more: a list comprised by the Department of Antiquities of the Republic of Cyprus www.mcw.gov.cy, marking early Christian settlements, Byzantine and late Byzantine churches and monasteries, as well as Medieval monuments, also noted the monastery of Panagia-ton-Kafaron-tis-Lapithou… which nowadays has been pillaged. Anyway, let’s get back to carving…

In the past, decorative motifs, of Greek and Byzantine origin, were used and can still be encountered today; for instance, in the form of gorgons (also mermaids) and angels. Amongst the other popular and traditional motifs, it is worth noting: cypresses, flowers in pots, birds, lions, palaces and churches, two-headed eagles and grapevine leaves.

Decorative carving covered various furniture items — the most common being chests — manufactured from local cypress or nut trees.

Other objects fashioned here by master craftsmen included: shelves, cupboards, chairs, tables, beds, door frames and more rarely — door panels, window frames and shutters.

The Cyprus Folk Art Museum in Nicosia has preserved rare folk etchings from Akanthou. These items and accessories, carved from the acacia tree, possess the same traits as their counterparts manufactured in Cypriot table workshops: they are painted in red, light blue, green or yellow. Combined with a large variety of patterns and bright pigments, they are also characteristic of the naive manner in which local artisans perceived life.

Various geometric plant and architectural motifs, as well as images of animals, birds and human figures, served as an additional decoration to wooden objects carved in Akanthou. Amongst them, there were also mythical images: angels, mermaids, fairy tale birds and animals.

Many researchers have observed the significant and long-standing (of course) influence of Byzantine art and the later influence of the gothic style in places of worship.

As such, regarding folk art, it can be said that in a number of cases, the division of “the mundane” and “the church” was rather relative.

Nowadays, despite the village being under Turkish occupation in the territory known as Northern Cyprus (Akanthou was renamed Tatlisou), several traditions have still been preserved and native residents, who have since left the village, continue to practise carving, crafting very popular and now traditional utensils or decorative objects. Amongst them, there are great craftsmen who specialise in restoring old furniture.

-

The village of Moutoullas, in the valley of Marathas, is also renowned across Cyprus for its craftsmen, whose tools still fashion elegant, carved lamps, mirror frames and large wooden trunks engraved with traditional folklore motifs.

The village is home to Panagia-tu-Moutoulla, a small, 18th-century church-chapel, dating back to the year 1280, construction on which finished much later, in the 16th century. It is one of the earliest examples of wooden construction with inclined roof rafting and closed wood shingles. This was typical of the Troodos region and became widespread thanks to the technique’s efficiency, an example of which can be seen on the famous monastery of Agios Ioannis Lampadisitis. The building, which features scenes from the Last Judgement, was introduced in 1985 to the UNESCO list of protected world heritage sites.

The ancient tradition of manufacturing hand-carved wooden baths and tubs has also continued in Moutoullas.

Alignments

Cypriot wood carving has traditionally been split into two alignments: the spiritual and the mundane.

Spiritual (church) carving flourished in the early 16th century; the appearance of the three-tier iconostasis in Cypriot church interiors, as well as in Orthodox ceremonies, is associated with this time in particular. The name “iconostasis” originates from the Greek “iconostasion” — an altar partitioning, which separates the altar from the remaining interior and runs from the north to south walls of a church; it has a local row of icons, a Festival Tier and a bust-length deesis. Both Cypriot and Cretian iconostases are very close to their Russian counterparts. Wood carving can be encountered on various objects in church interiors: thus, over time, amongst the cult applied art carvings, archbishops’ altars, candelabras, chairs, doors, windows and other items, began to appear.

The Barocco style wooden iconostasis, inside Larnaca’s church of Saint Lazarus, is a textbook example of ancient carvers’ creative works.

Mundane pieces, in turn, are split into two categories — urban and folk (rural). The “urban” category of wood carving includes all types of wooden furniture used by the urban population: wardrobes, tables and armchairs (“polithrones”).

The main characteristic of folklore or rural wood carving was its natural look, the unique method of self-expression demonstrated by the carver and the absence of any strict proportions, as well as the emphasised simplicity of its design. For instance: chests of drawers, chairs, shelves, cupboards and mirror frames. The carving on these objects, as well as the grandeur of the motifs and quality of material used, varied depending on the social status of the owner and the place where they were crafted. Wood was also used to manufacture agricultural equipment and household tools: ploughs, pestle and mortars, bread moulds, troughs, pack saddles, looms, shovels…

As we know, there are several methods and techniques used for working with wood:

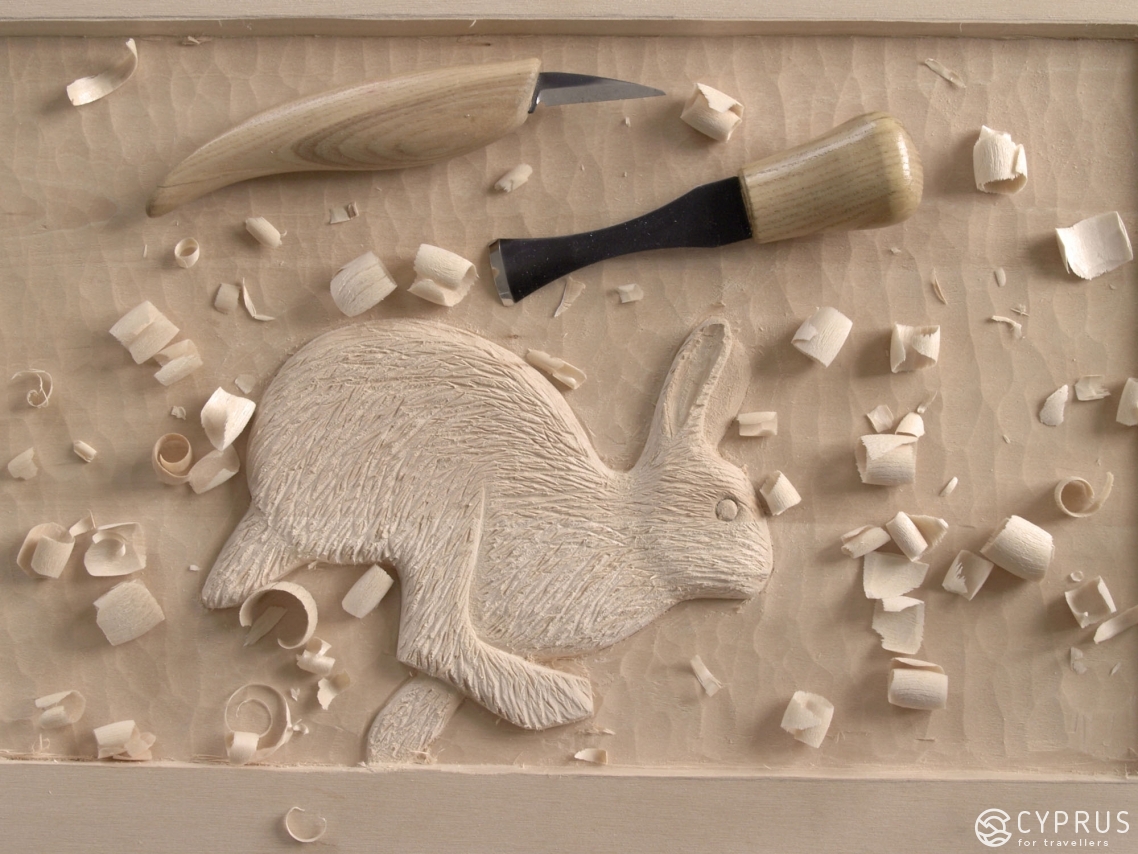

- Contour Carving — the simplest to perform: a pattern in the form of “grooves” — linear cuts inlaid in a flat surface (flat-incision carving);

- Flat-Plane Carving — a pattern is created through “selection” of a background by the craftsmen. The most common type of carving for animal and plant imagery;

- Relief Carving (contemporary masters often use this technique to craft murals) — all the carved elements are situated over a background, the elements have been elaborated with great detail;

- Fretted Carving — used in flat-relief and relief techniques. The background is removed completely. Fretted carving is known as an “open work”.

- Sculpture Carving — this is self-explanatory: three-dimensional images are created of objects and figures etc. either partially or completely detached from a background. This form of carving is very old and the most complex. Nowadays, masters often use a milling machine to copy objects.

Carvers have long used appliances such as benches, a carpenter’s plane, a chisel, angle blocks, saws and wooden hammers.

Now let’s look into the main types of timber growing on the island which are suitable for carving — pine, nut and cypress. As a result of the industrial revolution and mass market production, a huge number of inexpensive goods have appeared, many of which were made two-three centuries ago and are now deemed as old-fashioned.

However, a Cypriot craft service, under the auspices of the Department of the Ministry of Trade, has undertaken a noble “mission” to restore and further develop the age-old traditions of its nation.

Some of the best samples created by the island’s master carvers can be seen in Limassol Castle museum. A fragment from the wooden roof on the church of Mamas Luvaras in Troodos, dating back to 1455, is a fantastic example of this type of work.

If you’ve been thinking of buying a souvenir in Cyprus crafted from wood, then a carved bread bin, which Cypriot housewives still use to this day for storing bread or fruit, could be an excellent gift.

Do you fancy giving it a whirl and attending a master class, let’s say, in the capital? It couldn’t be easier: the Chrysaliniotissa Arts & Craft Centre is open in Nicosia (a small, yet curious complex, consisting of 8 workshops, located at the intersection between Iponaktos and Dimonaktos street, more info here), where young and adult Cypriots, as well as foreign guests, can grasp the basics of numerous crafts not limited to wood carving.

Address: Dimonaktos Street, 2,

Telephone: +357 22348050, +357 99629611

-

There are several contemporary master carvers who are well known on the island (you can encounter their works at regularly held exhibitions):

Andreas Evangelou — he crafts chests and mirror frames, as well as wardrobes, carved beds and traditional Cypriot souvantes shelves.

Andreas Charalambous — this local craftsmen fashions various items in modern and traditional styles: both church and mundane carvings. His website: www.toploumi.com.

The wooden creations of Iosif Yanashvili, a Georgian craftsman living on the island, centre around Cypriot motifs and adhere to local traditions: Byzantine icons and carved dishes.

Traditional Chair Manufacture — where carpentry and natural fibre weaving intersect

“Tsaeras” — the name given to someone who crafts chairs (“tsaeres” or the more common “karekles”) on the island. Construction of chairs in an urban style noticeably differs from those used in the island’s rural regions.

Now for a more detailed explanation. Until the recent past, there were two types of hand-carved chair which were incredibly popular in cities, among both Cypriot communities: one type had circular details, while the other was perfected in a rectangular shape. They were made from the wood of a cypress, oak, sycamore or mulberry tree.

The seating was made by wrapping the upper part of the structure with a rope (weaving) wound by local craftsmen from natural fibres.

Geometric patterns, used to decorate some “models”, were applied with wood carving tools.

Previously, craftsmen had needed to scour whole forests and groves in their locality before setting their eyes upon a suitable tree. They would then cut it down and leave it in place for several months so that it would dry out, as was necessary, after which they would begin to work on it.

“Chair” craftsmen, as a rule, began to grasp their profession as children: boys and teenagers would help their fathers and professional craftsmen while they spun ropes (“floudi”) used to weave seats and sometimes the backs of traditional chairs.

Bulrush fibre was used to spin the rope, with the thickness of the cord depending on the twisting method — if spun between the palms, the rope came out thin while working the rope with your thumb and index finger produced a thicker cord. Thick ropes were used when working with larger wooden items to achieve the greatest sturdiness and durability.

If previously this work was carried out in many of the island’s villages, then nowadays, rope spinning is done to order, mainly in Akrotiri, sending bundles to master craftsmen — manufacturers of Cypriot chairs.

Such chairs could once be encountered everywhere: in houses, cafes and taverns; many craftsmen, when crafting in their workshops and receiving clients, also used strong chairs with woven seats, sometimes decorated with carved patterns.

The comfort of these seats is due to the natural origin of the materials, the shape of the seating and its ability to allow air to pass through easily.

-

In fact, while on the topic of chairs, I’ve remembered how my father in law — who also used to be a professional carpenter and cabinetmaker — made a long queue when he ordered several such chairs from the town’s best craftsman.

They weren’t cheap, but having them in your home was considered prestigious and rather a necessity.

Recently, while visiting my mother in law, I noticed that all the now old chairs her husband had acquired 40 years ago, could still be distinguished due to their sturdiness and sound appearance, regardless of them having been in high demand over the years. They all had carved markings on them — the customer’s initials… meaning that business had been going well and clients were aplenty.

One peculiar characteristic of this craft was that chairs had long been crafted without the use of nails. All fitted aspects were secured with wooden pegs. The main material used was the local species golden oak, which grew on the igneous rocks of the Troodos mountains.

The craftsmen of today (who are now few in number) say: the woven surfaces on chairs have four zones: each zone has a different type of weave… in order to achieve the greatest sense of comfort when sitting down.

For those who are interested in buying such a chair for themselves, here are the contact details and address of a workshop:

The workshop of Yiannos Filaktou is located at the following address: Chanion Street 16, Strovolos (Nicosia).

Telephone: 357 99376605, +357 22511600

Opening Hours: Weekdays, 7:00-16:00.

As we near the end of this article, let’s address a “small point” (which recently became our favourite): what to do if you want to have a go at crafting something.

So, today, we’ll learn a little more about working with wood, as well as rope weaving and crafting original stools.

Wood, as the most available material practically the world over, has enabled craftsmen to achieve a significant level of expertise and the necessary results when manufacturing practical items and objects. It has also allowed them to engage in artistic crafting, involving the decoration of interiors, which has long attracted attention and is yet to fall into disuse.

Several pieces of advice from professional carvers

Tools

Modern carvers, in their work, often use more than just mechanical tools (chisels, various knives, angles and wood chisels, spoon chisels, axes, mallets, files and adzes etc); they also use electrical items (electric chisels with various settings, fret saws) — many appliances are already on sale as part of a set.

However, ready-made items can come with incorrect corner grindings, therefore if you decide to practise this craft seriously, professionals advise that you order high-quality steel instruments from specialists.

For those interested in openwork carving, we recommend buying a Dremel — a universal decorating tool.

Where to start? Buy a wooden block (you can always find lots of them in craft shops). You’ll need an air humidifier to maintain the optimal level of humidity required for preserving your work.

Types of Wood and their Properties

Lime — very easy to work with, therefore suitable for novices.

Birch — an excellent raw material with a clear-cut, pronounced relief. A sound choice when creating fine laid-on decor or stylish souvenirs.

Oak — known for its longevity and toughness, it is used for creating massive murals, while carved wooden furniture is not only beautiful but long-lasting too. The tree for the coolest of pros!

Nut — creates a very sturdy wood which can be easily worked on and polished. Used for a variety of items, ranging from furniture to accessories.

Pear — good in that it rarely bends and doesn’t crack. Highly artistic decor elements, interior objects and gifts can be created with it.

Pine, yew, spruce and cedar — decorative jambs and cornices are carved from these conifers, as well as sculptures.

Golden Oak — boasting a superb colour, it is often used as a replacement for more valuable woods.

Pay attention to the period when your wood was procured: the autumn-winter season is considered the most favourable. Thanks to sap flow slowing down, subsequent drying won’t bring you any trouble.

A word of advice: if cracks begin to emerge when drying the item, the best way to deal with them is to glue a piece of the same wood to the crack. If they are small cracks, then some putty will do the trick: table glue mixed with wood chipping.

With your own hands: a stool with a woven seat — an original interior piece which can be easily crafted.

You’ll need wooden legs and a chair frame — the base of your stool; some cord (rope made of natural or synthetic fibres) around 20 m; furniture nails; a hammer; a clamp; scissors; an awl; paint or wood dye.

Dress your wooden structure with wood dye, lacquer or paint.

Using a furniture nail, fix the end of the cord under the frame and begin winding it in the direction you’ve chosen: towards the frame planks opposite one another, rather tightly.

After 5-6 reels, clamp the cord and repeat to the end.

Nail the second roll of cord (one idea: use a contrasting colour) to one of the two remaining frames and begin feeding through the tightened reels: for “basket” weaving, alternate the rows. Don’t forget to fix the cord with furniture nails after 5-6 “turns”.

The cord will gradually increase in tightness making it more convenient to use the awl.

Fasten the cord underneath the frame. Your stool is ready.

Finally, for some inspiration and in order to expand your creative horizons, visit museums and exhibitions more often, walk through natural landscapes and of course, don’t forget about specialised sites.

[1] In the Hermitage collection, for instance, there is an exhibit which was discovered on the site of an ancient settlement: a carved spoon with a handle in the shape of a bird’s head, dating back to 3 B.C.

[2] New Renaissance art, preserving former traditions (famous scenes, biblical or mythological characters, everyday scenes characteristic of any age in history), fills them with something else, the centre and meaning of which is man: in all the baseness and grandeur of its nature.

[3] Contemporary archaeologists attribute Lapithos to the colonial settlement of the Lakonians (natives of Lakonia), which was built after the Trojan war (around 1,000 B.C.), “the authorship of the project” ascribes this to Praksandros, the first king in the region.

[4] An interesting note: Pantelis Pantelides (elder) released a book: “Akanthou. A village where Beauty, History and Legend meet”.

It’d also be interesting to take a glance, if you’re able to find them, at the travel notes of the English woman, Scott-Stevenson, who describes the village and its inhabitants in the 19th century in her work “Our home in Cyprus”.

Until next time, don’t go anywhere!