Cyprus and its countless generations of people have passed through close to 9,000 years of historical and cultural development. They have fashioned their own culture, constantly assimilating and sublimating the elements and influences of countries beyond the island’s borders; in doing so, creating a unique environment, both for language and art. Naturally, the long centuries of various nations taking dominion over the island speak for themselves. There have even been civilisations in Cyprus since the deep Antiquity.

All these factors have not only enriched the Cypriot people’s cultural experience but have helped their character burn brighter. We can find it reflected in the literary works of the past and present-day, as well as captivating speeches, proverbs, fairy tales and parables. For this reason, it is in folklore, first and foremost, where this reflection is evident.

Today, you’ll be able to open this page in Cypriot folk culture for yourselves.

Population

As we all know, the inhabitants of the Republic of Cyprus — both Greeks and Turks — are called Cypriots.

Greek-Cypriots (in Greek, Ελληνοκύπριοι) are the predominating population on the island, totalling close to 80% of all the country’s inhabitants (this number is in the region of 648.5 thousand people today). According to the 1960 Constitution of the Republic, aside from ethnic Greeks, the “Greek” population also encompasses the Maronites (Lebanese and Syrian Christians), Armenians and Catholics. These nations have long resided on the island and were provided with the opportunity to join one of the two ethnic communities (Greek or Turkish).

And so, our contemporary Greek-Cypriots are genuine descendants from one of the Ancient Greek tribes — the Achaeans (including the Mycenaeans, in part: from early 2,000 B.C.; in 7 B.C., they actively resettled in Cyprus and Asia Minor).

As such, from 2 B.C., the number of Greek settlers on the island grew sharply, and Cyprus was already on the way to being a valued and integral part of the Hellenist world. The Greek language rendered immense influence on this process, as well as on the development of the ancient tradition.

If to give a short recount of the historical events which influenced the formation and development of statehood in the country, then this was, no doubt, significantly on the part of Byzantium (after the fall of the Ancient Roman Empire (395), the island fell under Byzantine jurisdiction).

Eastern-Christian traditions (Orthodoxy) were also strengthened, including the famed event in the 5th century, when the Orthodox Church in Cyprus acquired the autocephalous status (431 A.D).

With the arrival of the Lusignans in the late 12th century (1192-1489) and the Venetians after them (1489-1570), the Greeks in Cyprus were subjected to a great deal of oppression. The new rulers tormented the Orthodox Church and its congregation.

During military operations in the 1571 Ottoman invasion (in the course of the Turkish-Venetian or “Cypriot” war, from 1570-1573, caused by the aspirations of Sultan Selim II to seize the island… the magnificent wine of Cyprus is considered to have served as one of the main reasons), close to 56 thousand Greeks and Venetians died, fell into slavery, or fled the island. Meanwhile, settlers from Turkey began to arrive in Cyprus.

So, we pass to another community of the Cypriot population, nowadays regarded as rather large and historically sophisticated — the Turkish-Cypriots (in Turkish, Kıbrıs Türkleri).

Naturally, as is the case with the arrival of any invader, especially one bearing a different culture and religious belief, a stream of burdens awaited the locals. Not only had the reality they were accustomed to categorically changed, but also its accompanying culture; the ethnic structure of the country’s population underwent a perceptible change.

According to the decree of Sultan Selim II, more than 5.5 thousand people relocated to Cyprus from the southern coasts of Asia Minor.

These were mainly arable farmers of modest wealth, as well as craftsmen (tailors, jewellers and others). However, alongside the peaceful folk, who settled in large families, Cyprus also witnessed the appearance of its former convicts: indeed, until the late 19th century, the island was considered unfit for living due to a malaria epidemic.

Naturally, the new power also concerned itself with supporting its position, by transferring its numerous armies to the island.

Part of the Cypriot Greeks accepted Islam — a move acknowledged as submitting to the Muslim invaders; meanwhile, in comparison to the Romans, the Turkish were known to have possessed a more patient attitude towards the Orthodox religion (at least to begin with). At that time, as a result of social changes, a whole number of spiritual sects [1] emerged, combining the traditions of both Christianity and Islam in their beliefs. Still, the majority of people — Greek Cypriots — remained faithful to Orthodoxy and the culture of their ancestors.

Thus from that moment and over several centuries since, both national communities have lived side by side on the island. Along with this, despite tense interactions between generations, each community has kept its own culture, which has remained separate from the other (interethnic marriages, for instance, have long been considered taboo).

The reign of the Turks lasted until 1878, only to then be replaced by the English (1878-1960) — thanks to them disseminating new orders of colonial administration, they contributed to an administrative-level split, as well as a division in education from an ethnic standpoint. The English were able to sow the seeds of mistrust between the two communities, which became the root of future strife: by that time, despite their disagreements, the Greeks and Turks had, on the whole, learnt to peacefully coexist on the island, even in smaller settlement regions. In fact, it was under the Brits, in particular, when a significant wave of Turkish-Cypriots migrated from Cyprus.

Simultaneously, the subject of reunification with Greece and the “enosis” movement (translated from Greek, meaning “union” or “unity” — reuniting with their “historical homeland”) was a significant period in the lives of the Greek community. Enosis had both its favourable (the rebirth and survival of the Greek language, traditions and the local Orthodox culture) and extremely negative moments (growth in nationalism and religious intransigence).

After Cyprus gained independence in 1960, the decision was made to create a government with 70% of representatives from the Greek population and 30% from the Turkish community (although, according to the census from that time, only 18% of those residing on the island were Cypriot-Turks. However, the “all-Greek reunification” mentality which continued to hover amongst the Greeks had acquired a shade of revenge, centred around the rebirth of the Greek state in the limits of the former Byzantine Empire. To a large extent, this mindset, with the support of the fascist (black) junta which seized power in Greece in those years (1967-1974), instigated the 1974 Turkish invasion and the unlawful occupation of the northern territories of Cyprus — an ongoing issue to this day.

As a result, the island was split into two parts based on ethnicity: the more significant Greek part (the territory under the control of the Republic of Cyprus) and the smaller part attributed to the Turkish lands in the North (by the way, the Turkish immigrants, who poured here in large numbers, have no relation whatsoever to Cypriot-Turks).

When leaving the country, a good number of Cypriots with Turkish ancestry preferred to leave not only for Turkey but also further onwards — for the countries of Western Europe [2].

Nowadays, a large diaspora of Cypriot-Turks (along with their fellow Greek compatriots) resides in Great Britain (close to 150,000 people), along with others: in Turkey (50 thousand), Australia (25 thousand) and Germany (10 thousand), as well as Canada and the USA (5 thousand). Besides, nearly 2,500 Cypriot-Turks still live, as their predecessors did before them, in the “southern” part of Cyprus.

Many Greek-Cypriots have now become refugees in their homeland. Some families have lost property and relatives; others have lost their lives — now they are either missing or being tortured by the Turkish military in prisons and camps. These losses were linked to the aggravation of the “Cypriot issue” which political scientists, despite all efforts invested, believe will unlikely be solved in the coming years. Many issues still remain unresolved due to the unrelenting and unlawful interference of Turkey in the internal affairs of Cyprus.

And yet, in 2004, Cyprus became a member of the EU and was recognised as an entire country, despite its socio-political issues.

On the whole, both Cypriot communities today — regardless of the dramatic pages in their history, as well as political manipulations and at times, conflicting interests — strive to become the unified people of an indivisible island.

Language

The following languages are officially recognised as state languages in Cyprus: Greek (both modern Greek and its Cypriot dialect are used) and Turkish (here we have an issue of diglossia: Turkish and the Cypriot “variation” used by the Oghuz group). English, French and German are the most common foreign languages on the island.

It would be interesting to find out how the islanders conversed in the distant and very distant past, wouldn’t you agree?

Cypriot syllabary [3] (linear), according to scientific studies, has three types: two pre-Greek — Cypriot-Minoan forms (both in use from 6 to 2 B.C.) and one Greek or “classical” script.

Did you know: the earliest inscription which has survived to our time was a sample of Cypriot script on a jug handle. It is dated to approximately 2400-2100 B.C. According to the Russian philologist, Tatyana Ventsel, there is a high likelihood that it was written in the language of an autochthonous people who inhabited the island before the Mycenaean invasion and the subsequent appearance of Cypriot-Mycenaean script [4].

Before the arrival of the Greeks, the primary language of the local, earliest inhabitants — the Tjekers — was known as “Eteocypriot” (it emerged and dispersed alongside the appearance of its people in 13 to 12 B.C.). The term itself, meaning “true Cypriot”, is used by researchers about a specific mass of discovered texts, including:

- Several hundreds of inscriptions dating back to 5-3 B.C.), which are impossible to read “in Greek”; though part of them are of Greek origin, they remain undeciphered due to the shortness of the fragments;

- Two-three groups of a particularly non-Greek origin. Here you can encounter extensive fragments with a morphology different to that of the Greek language.

No less than 100 texts, for instance, have originated from antique Amathus (inscriptions accompanied by text in Koine Greek — the principal, everyday means of communication); instead of Cypriot script, they have been written using letters from the Greek alphabet.

Another example: a group of short inscriptions was discovered on the site of an ancient settlement nearby what is now Athienou in the Larnaca region. Some researchers today (sent by Markus Egetmeyer, the German author of the fundamental Worterbuch Zu Den Inschriften Im Kyprischen Syllabar: Unter Berucksichtigung Einer Arbeit Von Almut Hintze, 1992) believe that this collection of written sources was penned in a language different to that of the Amathus people.

Characteristics of classical Cypriot syllabary:

- Consists of 55 signs (syllables or vowels);

- Written from right to left, sometimes changing or even alternating;

- Influenced the development of writing in Anatoli and most likely other writing styles in the region.

Cypriot-Minoan Syllabary

It is also presumed that earlier inscriptions, which were partly written in the decrypted Cypriot-Minoan script from 12-10 B.C., were also in this language (or one of two options: Eteocypriot or Philistine). In light of the chronological gap spanning over more than 500 years, this language is accepted as the “language of Cypriot-Minoan inscriptions”. Meanwhile, to this day, despite the morphological similarities, researchers still clash swords in scientific discussions over the language’s kinship to Eteocypriot.

Another bone of contention is whether the migration of the so-called “people of the sea” had an effect on the island's ethnic and linguistic structure. According to sources from beyond the island’s borders, in 13-12 B.C., the “Tjeker” people — relatives of the Etruscans — arrived on the coasts of Cyprus. Interestingly, from that moment onwards, traces of infiltration by Greek colonists gradually began to appear in the material culture of the island.

So, until 10 B.C., Cypriot-Minoan script was widespread across the island (the most significant concentration of discovered landmarks was observed in the Engomi polis and nearby a “bronze” settlement under the walls of the mosque of Hala-Sultan-Tekke — a monument well-known to many today. Later, in the following 300 years — accompanying the arrival of Greek colonists — a fall in the use of local script was witnessed, with its subsequent replacement by the language of the newcomers. Another 150-200 years later, inscriptions in Eteocypriot were only uncovered in the heavily hellenised Amathus.

Thus, to this day, this ancient script remains only partly decrypted (scientists have managed to identify only a third of all the signs).

Traits:

- The writing style of the island’s pre-Greek inhabitants is a derivative of Cretan linear script, and contributed to the emergence of classical Cypriot script;

- The script language remains unknown to this day.

Modern Languages of Cyprus

In our day, Greeks and Cypriot-Turks speak in Greek and Turkish dialects, which you can learn about by reading contemporary sources.

The main spoken and “original” language in Cyprus is Gibreiga. It traces its roots back to ancient Greek, which was widespread throughout the entire eastern Mediterranean in pre-Christian times.

Cypriot-Greek Gibreiga contains archaic forms which aren’t encountered in the modern language of Greece. Besides, according to specialists here, the language of the Greek-Cypriots was enriched over many years with a unique, multicultural vocabulary, influenced by Turkish, Italian, English, French and other foreign languages.

The Turkic language Gibrizlija — a version of Turkish introduced by the Ottomans in the 16th century — is also spoken on the island. It has been combined with York Turkmen and is still used in southern Turkey and Cyprus. Nowadays, Gibrizlija is spoken by both the descendants of Turks who settled in Cyprus many centuries ago; and the descendants of Greek Cypriots who were forced to accept Islam when the Ottomans arrived. You can also hear Armenian and the almost extinct Maronite Arabic dialect “Kormakiti” (its own name, “Sanna”, is rarely used today).

Curiously, specialists have noted that Gibrizlija, which developed on the island over five centuries, was also considerably impacted by Italian, English and partly by colloquial Greek languages.

Both languages are reflected and live on in a rich, poetic, epistolary legacy, which is voiced by their people… including in the art of shadow theatre.

The natural development of both Cypriot languages is considered to have ceased in the 1950s when the population was torn apart by inter-communal conflicts. This continued under war conditions and the post-war reality (after the 1970s) resulting from Turkey’s ongoing occupation of northern Cyprus.

In the present day, Cypriot scientists are striving to combine their efforts to revive the importance of local languages, as well as to raise the youth with respect for their own cultural roots [5].

Folklore

Like in any other country, the unwritten legacy of the Cypriot people, transferred from ear to ear, is an integral part of folk tradition — one which holds a special place in the island’s culture.

For want of a better word, this is “our everything” — folklore is a basic “life formula” which every person learns in their early childhood. It is a reflection of human existence and wisdom; of the acute observations engraved into centuries, culture and the memory of different countries and people. It is no accident that they sparkle brightly, like precious stones, enriching our language and conceptual thinking even today, beyond the borders of fashion and trends.

This wisdom of the ages, multiplied by the reverent attitude of modern Cypriots towards the legacy of previous generations — one which their far-gone ancestors also possessed — is reflected in proverbs [6] and, of course, in developed morphology (which we’ve already discussed).

As noted on the website www.cypriotacademy.com, folk proverbs, sayings and other idiomatic expressions said by Cypriots:

Proverbs and sayings, known as barimies, are an essential component of Cypriot culture. Many Cypriots, including expatriates, become well-acquainted with them during childhood. Barimies are the genuine quintessence of knowledge and experiences accumulated by the local elderly folk, passed down to future generations in the form of pithy and metaphorical statements.

Interestingly, if some Cypriot proverbs are linked to real events such as references to famous folk figures (e.g. the unfortunate baker, Haji-Markos); then others arise from verses in Cypriot chatista — a traditional off-the-cuff poetic repartee long practised in the villages of Cyprus.

Narrators — “piitarii” (those who are known here today by the western word “storyteller”) — have also been renowned on the island for a long time.

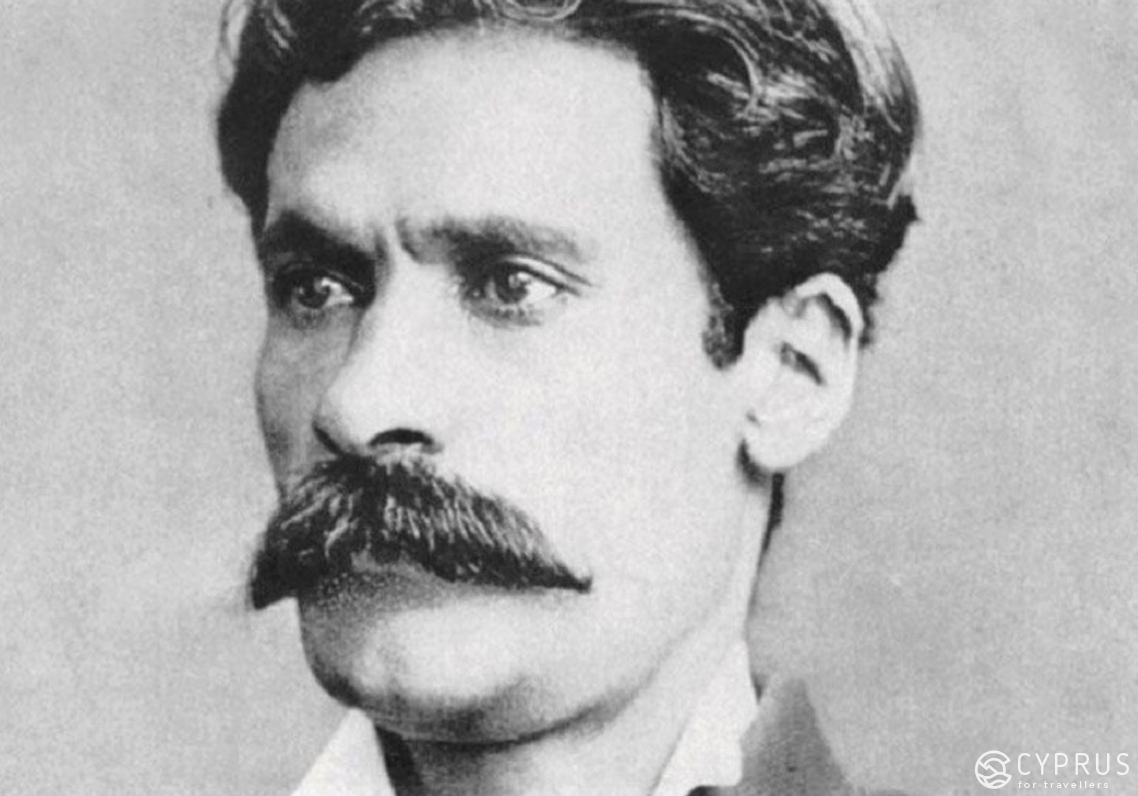

Amongst their ranks, those deserving particular renown are Vasilis Michaelides (1849-1917), a folk writer and poet (he wrote the poem “the Weak Lyre” (1882) and others); Dimitris Lipertis (“The Cypriot Songs”) and Pavlos Liasides — our contemporary, who writes in the Cypriot dialect. Carefully preserving the structure of folk poetry, the author enriches it in his early works with revolutionary romance.

As a rule, the leitmotif of storytellers focused on love for the homeland, aspiring for freedom and love poems.

What about Proverbs?

Proverbs cast a veil over the frequent pain and bitterness caused by the disappointments, struggles and tragedies which the Cypriot people have endured a great deal of throughout their history. Though concealed, they are no less vividly expressed through folk humour and biting imagery.

Here are a few of them:

«Άλλα λόγια θκιέ παπά» или «Άλλα λέει η γιαγιά μου, άλλα ακούνε τα αυτιά μου»

My grandmother says something, my ears hear something else

English Version: The young do not listen to the old

«Αθκιασερός παπάς, θάφκει τζαι ζωντανούς»

English: Time flies when you’re busy

«Αλλού τον τρώει τζαι αλλού κνίθεται»

English Version: The squeaking wheel gets the grease

(The most noticeable problems are the ones which get attention)

«Απόν απέξω του χορού, πολλά τραγούδια ξέρει.»

English meaning: Shame should not come from a lack of knowledge, but a lack of learning

«Aπόν αντρέπεται, ο κόσμος δεν δικός του»

He who feels no embarrassment owns the world

English Version: Better to be poor with honour than rich with shame

«Πέψε τον πελλόν τζαι λάμνε ταπισόν του»

English Version: “If you want something doing, do it yourself

«Ότι θυμάται χαίρεται»

He rejoices at whatever he remembers

English Version: You can’t change the past

And finally…

«Ο νούρος του σκύλου δεν ισιώνει»

English Version: A leopard can’t change its spots

And a similar one:

«Ο κάττος τζι’ αν εγέρασεν τα νύσια που ‘σιεν έσιει.»

English Version: Even an old cat has the same claws as before

(Once a person’s basic character has been formed, it cannot be changed)

The most comprehensive guide I’ve managed to find on Greek proverbs is here: www.kuprienko.info and www.greek-language.ru.

This site will be of interest to native speakers of English: www.proverbicals.com.

Traditional Cypriot Stories and Folk Tales [7]

The Clever Donkey [8] (Ο έξυπνος γάιδαρος)

Once there was a donkey, a young boy and an old man. And they passed through three villages.

At the first village, the young boy was on the donkey, and the old man was pulling them. The villagers saw the old man, who was sweating, and they said, “Isn’t the young boy ashamed? Having the old man pull them in this heat!”

At the second village, the old man was on the donkey and the young boy was pulling them. The villagers saw the young boy, who was sweating, and they said, “Isn’t the old man ashamed? Having the young boy pull them in this heat!”

In the third village — having learnt from their previous experience and not wishing to again become a source of mockery and reproach in the eyes of the people — both the old man and the boy hoisted the donkey onto their shoulders and carried him.

The people of the third village, after seeing such a wonder — a relaxing donkey and his exhausted “carriers” — they uttered with delight at what they’d witnessed: “What a clever donkey!”

The Three Instructions of Banikos the Carpenter (Οι τρεις συμβουλές του Πανίκου ο ξυλουργός)

In the old days in Cyprus, a young couple were wed in a small village. They were very poor, with no inheritance. Soon after their marriage, the young husband had to go far away to find work and earn money for his family.

He arrived in a town where he began to work with a carpenter by the name of Panikos. In those days of old, run of the mill people could not read or write, and he couldn’t even pass on any news to his beloved wife. And so the years went by...

After a long while, the man resolved to return to this village.

“Go to good, my so”’, said his boss. ‘I have don’t have enough money to help you, but I’m going to give you three valuable instructions — try to remember them’, said Banikos the Carpenter:

- First, when you see people stealing, you must not follow their example

- Second, when you see people fighting, you must hold back and not interfere

- Thirdly, when something annoys you, you must again remain calm and suppress your ange

At that moment, the man needed money, not wise advice. Still, he thanked his wise instructor and bid farewell, then set off for his home. On his way, he noticed two or three men stealing apples from another’s orchard. As he was hungry, the man thought to try stealing a few himself. However, he remembered the first instruction of Banikos the Carpenter and changed his mind. Meanwhile, those who had been stealing were caught by the police.

Further on, the traveller stumbled upon two strangers about to fight one another. He was going to pull them apart — they looked enraged. However, the second instruction of the wise Banikos the Carpenter came to mind, and he managed to change his mind in time: meanwhile, the fighters went for their knives and threw themselves at one another with renewed force.

Night descended, and the man finally arrived home. He opened the door and entered. It was fairly dark. He saw his wife, but she didn’t recognise him. Before he was able to speak with her, an unfamiliar fellow entered, young and tall. The husband was enraged at them both but didn’t let it show in his face. The time had come to remember the third instruction of Banikos the Carpenter…

“May I stay here tonight?” the man asked his wife, not revealing his identity.

The wife indicated to a bench in the open air and said “Sleep there if you want. I won’t turn you away”.

Fatigued by his long journey home and tormented with suspicions and doubts, the man fell asleep. In the morning, the door opened, and the man saw his wife saying goodbye to the young man as he was leaving, softly kissing him on the cheek. The man could contain himself no more.

“Who is this lanky fellow you’re kissing?”, he asked the woman. “I’m your husband. Don’t you recognise me?”

“In last night’s darkness, how was I supposed to have recognised you after so many years”, the wife answered. “My love, this fine young fellow is our son. I named him Banikos!”

It was at this moment when the man realised the value of the three instructions. Now, he knew that he would remember Banikos the Carpenter forever [9].

Modern Folklore or an “Epic Literature” about Andrikos

I wonder if you’ve heard of him? For starters, “Andrikos” is the collective image of a Cypriot, who:

- Is either a charming person or prefers to think about himself,

- Concerns himself day and night only with matters of business (as a rule, their own shop),

- Can’t be pictured without a spot of Cypriot brandy,

- In appearance — he is “a reasonably well-fed man and (always!) in his prime (paraphrasing Astrid Lindgren’s description of the famous “Karlson”).

In general, it must be said that the phenomenon of “Andrikos” — another modernised quintessence of Cypriot inhabitants’ folk wisdom — essentially burst into widespread use in the late 1980s. Moreover, this happened beyond the island's limits: in Great Britain, thanks to the diaspora of Greek-Cypriots living there.

So, there was a well-known columnist in those years, named Andrikos, who worked at the English version of Parkiaki, a community newspaper for Cypriot emigrants. In his feuilletons, he made well-aimed, but friendly jokes of himself and his fellow countrymen — representatives of the “first wave”. Jokes about their undying conservatism, as well as them favouring old mentalities and habits so different from those back home. Andrikos and his “namesake” proved to be so incredibly popular amongst readers that a set of his famous columns was released in 1993 in a separate publication.

In 2003, thanks to generous financial support from the Bank of Cyprus UK, Andrikos made a triumphant return as a character in a radio play for LGR (103.3 FM, starred in and directed by Peter Polikarpou).

Besides, Polikarpou issued a casting call, announcing that he was looking for talented young Cypriot actors to take part in a new show (originally named “The Brox”).

In fact, the director had a vision:

And now a little more detail about this cheerful and sharp-minded character.

Born in Cyprus, Andrikos was always a loud-mouthed, somewhat self-assured man, forever proving himself to the extreme (both in his job and family life)… meanwhile, the members of his classically Greek family were always in a slight state of tension when Andrikos the magnificent was at home, though all he could notice was love and adoration…

It is no accident that this was how he behaved with those close to him.

Regarding his devoted wife Joanna, a woman of 40 years and more, with a strong Cypriot accent, she had everything that she could’ve wanted… Everything, except a life full of personal interests and a variety of hobbies.

Andrikos’ love for his daughter Maria — a hairdresser a little older than twenty, who hungered for freedom — also had its nuances. It was her father who would choose her future partner (spouse), as well as decide — whether she liked it or not — if she would wed the sensible and reliable accountant Spiros.

Despite Andrikos’ admiration for his eldest son Nigos, a student and fun-lover, he also wasn’t left with a choice in life. Nigos had to seize all the opportunities which his father, Andrikos, had squandered in his childhood: a good education, the best job prospects and a lot of money to happily spend on cars and the beautiful ladies he would one day meet.

Paternal care for Andrikos and Joanna’s youngest son, the bright young schoolboy Dagis, came no more naturally. He was obliged to appreciate the rich culture and tragic history of his ancient historical homeland.

Dagis was very well destined to inherit the intricate “world view” held by his father, along with a highly entangled philosophy on life and Andrikos’ warped sense of humour.

Thus, this form of comedy solved the issue of “fathers and children” amongst the Greek-Cypriot community in England.

The brave, bold and often pompous Andrikos was equally capable of displaying, warmth, generosity, and above all, unconditional love for his family.

The main thing was that despite everything, this love was mutual. Filled with determination to enjoy the freedom which life in northern London could offer, Andrikos’ children also wanted their “old man” to be happy. But could it be done?

Here is Andrikos’ poem, where, in broken English, the main character talks about himself:

“My name is Andrikos. I was born near Nicosia.

Many years ago, my friends, I come to live in ’ere.

I settle down in Captain Town to make a decent life.

Got work in a restauran’, found myself a wife.

But one mistake I make, my friends, and this I have to mention.

I been too busy makin’ cash to give my kids attention.

And so they just speak English now — is no flippin’ good.

We can’t really communiskate ’cos they no understood.

Now speakin’ of my health, my friends, I really can’t complain.

In Gibros I was overweight, in ’ere I just the same.

But how I feel inside, my friends, is hard to find expression.

My children no relate to me, too late I learn my lesson.

And so the opus ends:

…And then to see my village free will be my final wish”.

“The Poems of Andrikos” include separate stories about the members of his family — Maria, Nigos, Dagis and Joanna.

Here is the link for those interested: www.cypriotacademy.com

To learn more about contemporary and classical storytellers, as well as their works, please visit the evening events held in cultural and educational centres, as well as the Bread Museum in Limassol.

Cypriot Literature

Amongst other things, we will speak here about literary works “native” to Cyprus, which have been composed mainly in Greek, Turkish and/or other languages, including French and Italian.

From the distant past right through to contemporary times, the island, along with its reality and history, has inspired many talented individuals: young, well-known experts native to foreign countries, for some of whom Cyprus has become a temporary shelter or even a genuine home… Whether you’re aware or not, since the Antiquity, the main genre of literary works on the island has been poetry (rather like in Greece, where prose formed “only” in the 19th century).

The Middle Ages and the Antiquity

Literary relics of the Antiquity include the famed “Cypria” (deriving from a widespread form of address used for the goddess Aphrodite). It is also the fifth part (“the Cypriot Tales”) of an epic cycle, likely created in late 7 B.C., which is attributed to Stasin. The famous “Hymns of Home” are also dedicated to Aphrodite.

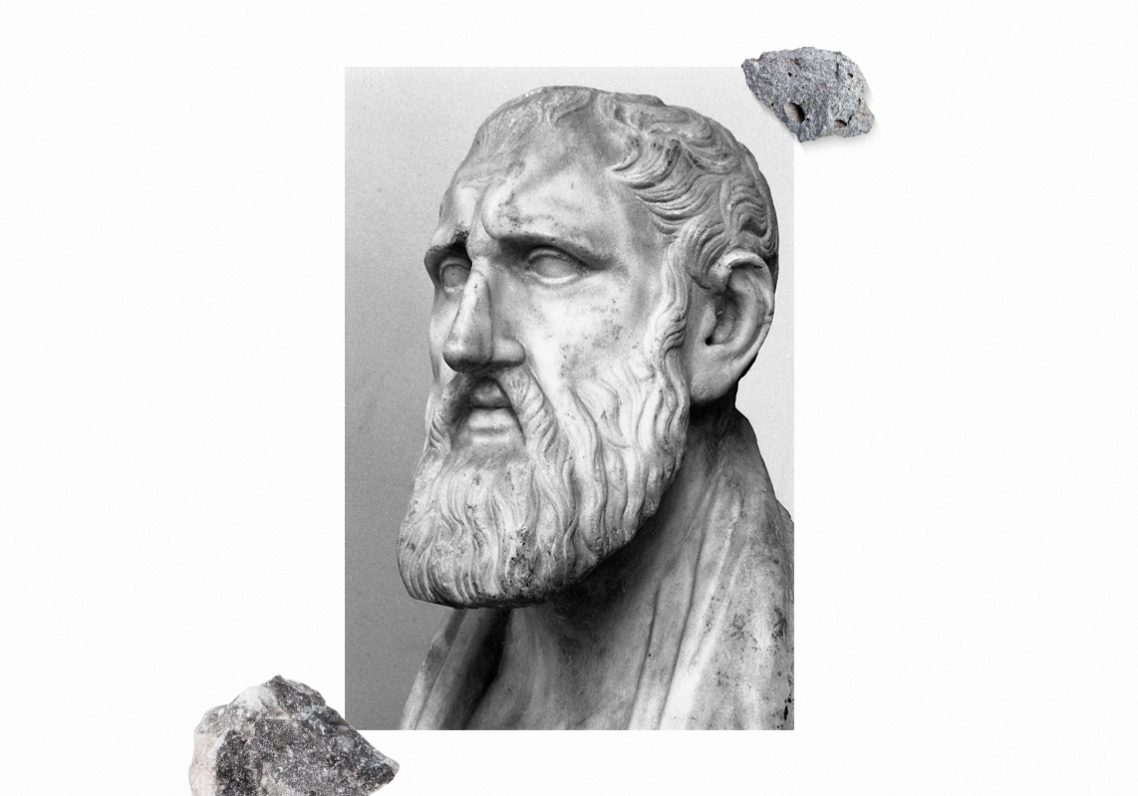

The philosopher and war chief, Zenon of Citium (334-262), was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy. Its writings on etiquette, poetry and physics were famously laconic, but have practically ceased to exist in our time. He was succeeded by his friend, pupil and a future archon of Corinth, Persaeus (306-243 B.C.).

Cyprus is, somehow, also a figure in early Christian literature: “The Acts of the Apostles”, which the apostles Barnabus and Paul preached on the island (see our articles: Kalopanayiotis, Monasteries of Cyprus, Tourist Paphos and more). Amongst the Byzantine (native to and from beyond the island) medieval writers, historians and travellers, as well as those from the medieval age, it’s worth noting: Leontios of Neapolis, Altheides and Patriarch Gregory II of Constantinople. Amongst everything, the appearance of the Byzantine so-called epic poetry, a striking example of which is the "Acrean Songs" (VIII-X centuries), dedicated to the life and exploits of the legendary Digenis Acritus, flourished in the Middle Ages.

The Late Medieval Age and the Renaissance

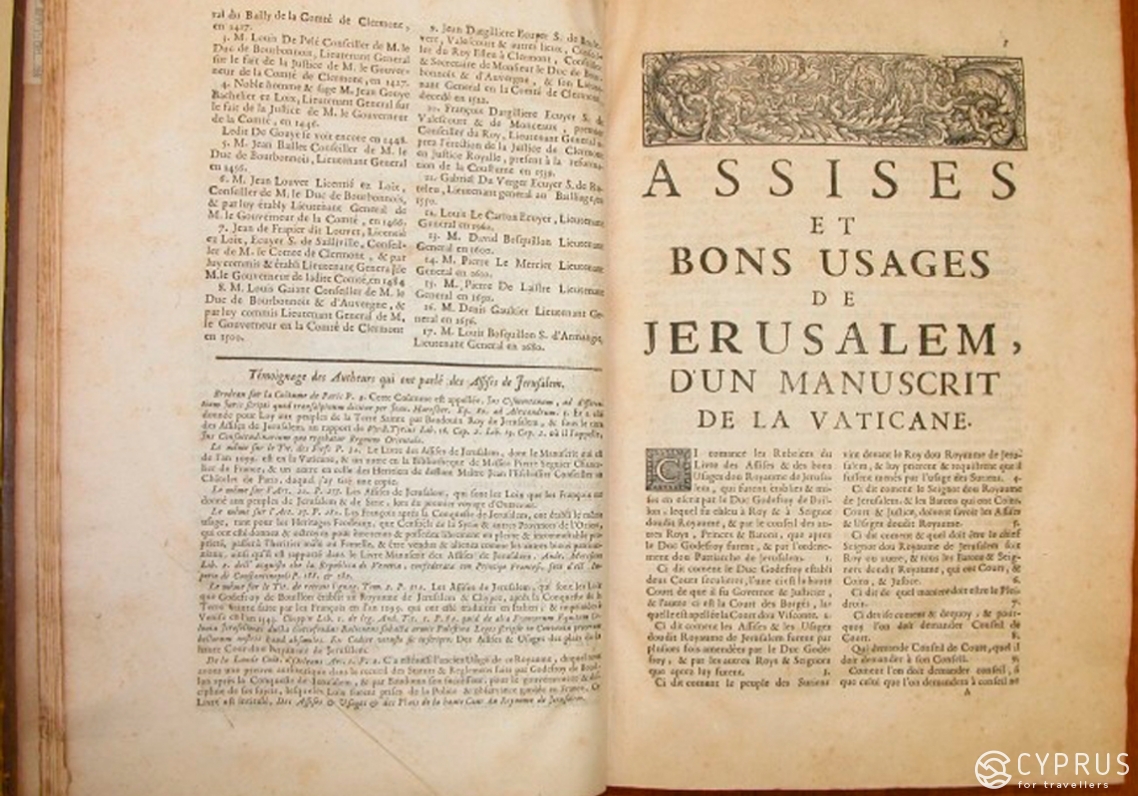

The legal treatises of the Kingdoms of Cyprus and Jerusalem — where the crusaders resided in the Middle Ages — are known as the “Assizes of Jerusalem” (13th century). These tractates were scribed in two languages: the local Greek dialect of that period, as well as in old French. In 1531, the Assizes were translated into Italian and remain to this day the most extensive collection of preserved medieval laws.

As for lyrical works from the era of Venetian reign, we are well acquainted, for instance, with the poem-song “Arodafnousa” about the French King Peter I of Lusignan and his love (1328-1369) for a beautiful woman from the Paphos hamlet of Choulou.

Regarding chronicles, researchers consider the most significant medieval works to be the “Chronicle” of Leontios Machairas, a writer, diplomat and simply… a friend of the king; as well as his successor, the chronicler Georgos Voustronios, and authors from the 15th-early 16th century, who describe the periods of Frankish and Venetian rule. The particular source was, by and large, written in the local (Greek) dialect, which in that period had adopted many French terms and their assimilations.

An extensive collection of sonnets and love poems, written in what is known as “medieval Greek”, date back to the 16th century when Cyprus was under the possession of the Venetian republic. In several of them, connoisseurs can see the apparent proximity to the manner of the Italian Francesco Petrarch, as they were, in essence, a translation of his works) Translations of the contemporaries Bembo, Ariosto and Sannazaro, were simultaneously widespread in society.

Incidentally, the same applies to William Shakespeare’s famous “The Tragedy of Othello, The Moor of Venice” (1604). The primary source of Shakespeare’s masterpiece is considered to have been a composition by the Venetian writer and scientist Giovanni Batiste Giraldi (his contemporaries appended him the nickname Cintio), the main plot of which is set in the fortress at port Famagusta during the reign of the Venetians.

-

In the second half of the 19th century, a new rise in literary works was witnessed on the island: inspired by events linked to liberation movement against the Turkish yoke, many authors dedicated their works to themes of war and raising self-awareness amongst fellow countrymen. This inspiration was further instilled by resistance to the yoke’s “godparents” — British colonial rule and the propagation of foreign orders in the country. Sentiment in Cypriot society, the people’s assonance and the acquisition of moral support from Greek revolutionaries and heroes all served to merge the Greek literary traditions of both countries by the early 20th century; the influence of Greek romanticism also became noticeable on the island.

The Modern Age

This began roughly in the mid-20th century, when in 1959, the country’s own literary magazine, “New Age”, appeared. With the dawn of independence came the emergence and development of various creative writers’ and poets’ unions, and in 1978, the Cyprus Writers Union was formed [10].

Of the great, contemporary Cypriot writers who have written in Greek, it’s worth mentioning names such as the poet and writer Costas Montis [11] (1914-2004) — some lyrical and philosophical compositions in both native Cypriot and literary Greek belong to his pen. The others: the poet Kyriakos Charalambides, the prosaist Panos Ioannidis, the poet Michalis Pashardis, the poet and translator Stephanos Stephanides; the poet and writer Nicos Nicolaides (1866-1956); Stylianos Atteshlis, the poet Demetris T. Gotsis, as well as Dimitris Lipertis, Vasilis Michaelides and Pavlos Liasidis. All of them are poets whose verse masterpieces were written, for the most part, in the Cypriot-Greek dialect.

Loukis Akritas (1909-1965), the famous Greek state activist, historical romantic and journalist, was also of Cypriot origin, born in Morphou.

One of the leading poets of today, Georgios Moleskis, graduated from Moscow State University with a Doctorate in Philology, having defended his thesis on how the poetic works of V. Mayakovsky are perceived in neo-Greek literature.

I’d like to bring your attention to one of his most amazing poetic works (translated from the Greek by Irena Ioannides) [12]:

The Water of Memory

Unfulfilled our plans for Sunday excursions.

We leave always for the south

return to a Nicosia in inertia

that gazes at Pentadaktylos

in the violet of the twilight hour...

And as I look at you and you at me,

Pentadaktylos,

I wander amidst your peaks

in my own fairy tale.

I cross to the opposite bank and sink

in other times,

in days when the sea blossomed with smiles,

in other tragedies,

in other outbursts...

And to the children that always ask about this wall

I tell a story

about the good, about the bad

and as always in fairy tales,

good triumphs over all,

the hero enters the palace,

or,

fetches at the last minute

the water of immortality and the water of memory.

1998

It goes without saying that it would be a sin not to mention the ranks of Cypriot-Turkish, who were also phenomenal poets, writers and prosaists.

The poets Osman Türkay; Mehmet and Heche Yaşın, Neriman Kahit, Fikret Demirağ and others all composed their works in Turkish.

The creative works of the prosaists N. Ebeolglou, Ouzker Yaşın and H. Mapolar are worthy of distinguished merit.

Neşe Yaşın is a famous poet and prosaist, many of whose proses have already been translated from Turkish to Greek and English. In 2002, her novel “Secret History of Sad Girls” was banned on the territory of so-called Northern Cyprus and in Turkey.

Another author, Sevgül Uludağ, has been an investigative reporter for 30 years: her activity has been of great significance in uncovering information on thousands of Greek-Cypriots who went missing during the Turkish invasion, along with the initial occupation of the island’s northern territories in 1974.

This courageous woman was awarded for her bravery.

Urkiye Mine Balman (neé 1927) — another talented woman and author of a series of books, writes in various genres. Her main creative works, however, are romantic poetry, sometimes describing the feelings of a lonely village girl or pastoral life as a whole. She also writes about long-distance relationships. Balman’s works have been published in several prominent literary journals in Turkey, such as Yesilada, Türk Dili and Türk'e Dogru; in 2017, she was awarded a prize at the Ali Nesim Literature Awards as a leading poet.

The creative works of the dramatist, Fadil Korkut, are also of particular renown. His plays: “the Sultan Jam” and “the Bride Veil” received high critical and public acclaim.

Amongst the writers living and working in Cyprus who have penned works in different languages, Nora Nadjarian — an Armenian poet and the amazing author of some short stories — is worth special mention. She writes in Armenian, English and Greek (“Republic of Love”, “Ledra Street” and others).

Today, creative works linked to Cyprus, which have been written by Cypriots who were born and grew up abroad after the emigration of their parents, are considered foreign works.

These authors mostly write in English.

We’ll name several of them: Andreas Koumi, Miranda Holparos, Stephen Lafton — a playwright, Christy Lefter (born 1980), Eve Makis, Michael Paraskos (born 1969) — a writer-novelist; Stel Pavlou (born 1970) — a writer and novelist (“Code of Atlantis”, 2001) and scriptwriter; Stefanos Stefanidis (born in 1951) — a poet-translator, ethnographer and documentarist. There is also Paul Stenning — author of more than 20 books; he’s a columnist in The Cyprus Weekly and the writer of Archbishop Makarios III’s biography.

For many centuries, Cyprus has inspired many foreign authors' works.

One of the most famous authors was Lawrence Durrell in the 20th-21st century (1912-1990), who worked on the island from 1952 thru 1956 as the former editor in chief of the “Cyprus Review”. Here he completed “Justine” — the first book in “The Alexandria Quartet”; and “Bitter Lemons”, for which he received the second Duff Cooper Prize ever awarded, in 1956.

Cyprus and its culture proved to be close to the Nobel laureate Giorgos Seferis (born Seferiades, 1900-1971), a native to Greece, as well as a distinguished poet and prominent diplomat. Arriving in 1953, he immediately saw a lot of things on the quirky island which reminded him of his childhood in far-away Smyrna. He wrote one of his most highly-regarded works (Ημερολογια Kαταστρoματoς) during his diplomatic posting on the island.

Here is one of his poems, inspired by Cyprus:

Helen

The nightingales won’t let you sleep in Platres.’

Shy nightingale, in the breathing of the leaves,

you who bestow the forest’s musical coolness

on the sundered bodies, on the souls

of those who know they will not return.

Blind voice, you who grope in the darkness of memory

for footsteps and gestures — I wouldn’t dare say kisses —

and the bitter raving of the frenzied slave-woman.

The nightingales won’t let you sleep in Platres.’

Platres: where is Platres? And this island: who knows it?

I’ve lived my life hearing names I’ve never heard before:

new countries, new idiocies of men

or of the gods;

my fate, which wavers

between the last sword of some Ajax

and another Salamis,

brought me here, to this shore.

The moon

rose from the sea like Aphrodite,

covered the Archer’s stars, now moves to find

the heart of Scorpio, and alters everything.

Truth, where’s the truth?

I too was an archer in the war;

my fate: that of a man who missed his target.

Lyric nightingale,

on a night like this, by the shore of Proteus,

the Spartan slave-girls heard you and began their lament,

and among them — who would have believed it? — Helen!

She whom we hunted so many years by the banks of the Scamander.

She was there, at the desert’s lip; I touched her; she spoke to me:

‘It isn’t true, it isn’t true,’ she cried.

‘I didn’t board the blue bowed ship.

I never went to valiant Troy.’

Breasts girded high, the sun in her hair, and that stature

shadows and smiles everywhere,

on shoulders, thighs and knees;

the skin alive, and her eyes

with the large eyelids,

she was there, on the banks of a Delta.

And at Troy?

At Troy, nothing: just a phantom image.

That’s how the gods wanted it.

And Paris, Paris lay with a shadow as though it were a solid being;

and for ten whole years we slaughtered ourselves for Helen.

Great suffering had desolated Greece.

So many bodies thrown

into the jaws of the sea, the jaws of the earth

so many souls

fed to the millstones like grain.

And the rivers swelling, blood in their silt,

all for a linen undulation, a filmy cloud,

a butterfly’s flicker, a wisp of swan’s down,

an empty tunic — all for a Helen.

And my brother?

Nightingale nightingale nightingale,

what is a god? What is not a god? And what is there in between them?

‘The nightingales won’t let you sleep in Platres.’

Tearful bird,

on sea-kissed Cyprus

consecrated to remind me of my country,

I moored alone with this fable,

if it’s true that it is a fable,

if it’s true that mortals will not again take up

the old deceit of the gods;

if it’s true

that in future years some other Teucer,

or some Ajax or Priam or Hecuba,

or someone unknown and nameless who nevertheless saw

a Scamander overflow with corpses,

isn’t fated to hear

messengers coming to tell him

that so much suffering, so much life,

went into the abyss

all for an empty tunic, all for a Helen.

Translated by Edmund Keeley

The British writer Paul Stuart is a novelist, romance author and academic who also moved to Cyprus. His first novel, “Now and Then”, was published in Cyprus by Armida Press in 2014. He also released two books about Samuel Beckett: “Sex and Aesthetics in Samuel Beckett's Works” and “Zone of Evaporation: Samuel Beckett's Disjunctions”. He has also authored the poem anthology “And Other Elsewheres” (2011).

Not only did the island become the inspirational start for his new writings, but also the setting of “The Sunrise” — a novel by the British writer Victoria Hislop (the plotline is developed around the dramatic events of 1974; published in 2015). “The Island” — an earlier novel by her (received by the Richard & Judy Book Club for their 2006 Summer Reads) — became the basis for the series “To Nisi” on the Greek TV channel MEGA, which was very popular in Cyprus.

Another British subject, Daphne du Maurier (lady Browning, 1907-1989), was an author of psychological thrillers and biographies, who first came to Cyprus in 1936. She was blown away by the beauty of the Troodos. There, she penned the famous “Rebecca” (1938) — a sample of a modern gothic novel, known today all over the whole world, thanks to the screen adaptation Hitchcock (there have been 11, the most recent was an Italian version, from 2008).

The Israeli novelist, Yishai Sarid, born in 1965, into the family of the famous politician and journalist, Yosef Sarid, wrote the bestselling detective story “Limassol” (2009).

In 2011, the author was awarded the Grand Prix de Littérature Policière for the second book in his creative resume, translated into eight languages.

Until Next Time!

[1] Research by the Maronite Institute of Scientific Research, MARI, was partly dedicated to this issue.

[2] According to the research of Kyriakos Kousoulidis and information provided by the ATCA (Association of Turkish-Cypriots Abroad).

[3] The script was only decrypted in the late 19th century by the Brit, L. Smith and the German scientists, M. Schmidt and I. Brandis.

[4] Inscriptions were found in Cypriot-Minoan or Cypriot Minoan script, which was used from the XIV thru XI B.C. (the majority of them date back to 1275-1200 B.C.).

[5] Find more on Cypriot literature here: www.cypriotacademy.com

[6] The original text was published on the 10th April 2017 in “Heart Cyprus”: www.hcbeat.com

[7] Did you know: the local dialect was traditionally used and encountered, for the most part, in folk songs and poetry, including τσιαττιστά (fighting, heroic poetry) and ποιητάρηες (a bard’s song).

[8] Interestingly, similar stories to this one — about how public opinion was capable of influencing a person (probably, from Arabic folklore) — are present in all cultures.

In our day, everyone knows or has heard of Hodzhia (Mulla) Nasreddin, as well as folk anecdotes and the wise Sufi parables about him.

[9] Taken and translated from: www.cypriotacademy.com

[10] The present-day Union has united close to 100 authors. Since 2013, its chairman has been the poet Georgios Moleskis (born in 1946).

[11] Montis was also known for his joint collaboration with Andreas Christophidis in compiling an Anthology of Cypriot Literature throughout the entire island’s existence (published in 1965).

Until the Anthology’s publication, the most famous piece was considered “A History of Greek Literature”, published in 1938 by the Cypriot writer M. Hadzhidimitriou (under the literary pseudonym Alitersis).

[12] Taken from the materials of the “Literary Newspaper”: www.lgz.ru.