All of us have been to Troodos, at least on occasion. Many of you living in Nicosia and its surrounding areas are well acquainted with the names of these villages — the first reference points at the end of the A9 highway. They habitually flicker on signposts, heralding the great moments, as well as the phenomenal views and ancient dwellings, which lie ahead.

Today was our day off, and we decided to change our customary route. Instead of heading for the alluring mountains and evergreen forests, as well as the familiar sights of Evrychou, Kakopetria, Kalopanagiotis and other well-known, appealing spots, we came off the Leoforos Nikosias highway (B9) to go in search of adventure and new experiences.

The habitual Sunday mainstream was upon us, with its multiples of cars, crammed full of people and equipment for outdoor activities. Their drivers were frantically accelerating and impatiently signalling each other along the road into the mountains. After falling out of the chaotic traffic, we dived into a side street and immediately entered the silence of village life, with no cause to hurry. The main appearance and decor hadn’t changed in centuries.

To find out what came out of this, please carry on reading…

Akaki

Akaki — with its natural, fertile forest lands (olive, citrus and date trees etc), memorable landscapes situated on the backdrop of the Kyrenia Mountain Ridge and various sights, little known still to the general masses of tourists — is located in the western part of the Messaoria valley, 22 km to the west of Nicosia.

The village is traditionally linked to the name of its first settler, an arable farmer named Akaki. The name is said to have been very common in the Byzantine era (it meant “peaceful” and “good-natured”; it’s quite difficult not to be reminded here of Akaky Akakievich — the touching protagonist of Gogol’s “The Overcoat”). Akaki can be seen on Venetian maps under the name Acachi; according to references from historians of the past, the lands here formed a fiefdom (a piece of land allotted to a liege by a signor) known as Acaqui, Achasi or Achaci. Indeed, in reality, Akaki was long ago under the rule of King Henry. As such, people began to settle in the region en masse in the last third of the 15th century (more precisely, in 1470, when the plague had fallen on Cyprus and people, forced to flee the disaster, came to these parts).

According to sources, including censuses, the most significant influx and natural growth in the population of Akaki fell over a long period: from 1881 to 2001. For instance, if in 1960, the overall number of residents totalled a little more than 1500 people, 1355 of which were Greek-Cypriots and 156 representatives of the Turkish community; then soon after the 1974 Turkish invasion, 623 Greek-Cypriots arrived in the village as refugees from the North of the island.

The main occupation of “Akakians” is first and foremost agriculture. Aside from growing wheat and other grains, as well as vegetables and citrus fruits, various types of domestic cattle are also bred here (mainly cows and sheep).

The remaining villagers of all ages work in different specialities in the capital. Today’s Akaki continues to grow and prosper thanks to the unrelenting growth in its population: the community has schools, a nursery, a local medical centre, postal service and banking establishments etc.

Would you like to learn more about the village and its locals? That can be done with ease: go to the centre of the settlement, look around, have a wander and interact with people. We did the same after failing to park in the central square (we’ll come back to this later), due to a lack of knowledge about the cobweb of local side streets, and we slowly drove further and further in search of a convenient “parking spot”…

Akaki's streets are a rather curious spectacle, not just due to the scenic mixture of styles and eras in the local building designs. Nor the abundance of greenery, with its mighty cactuses and soaring palm trees; but also thanks to the wide irrigation canals open along the roads, full of water seething through them.

So, it’s worth having a think about if you’re coming here by car!

The short search led us out to another small square — an intersection of Kiniras and Vyros street, which connected at the small, stone church of the Archangel Michael. This is a slightly modernised and well-kempt spot. Soon after, one of the locals hurried over to where we were and invited us to go inside.

We got acquainted with him and had a chat. Mr Andreas Appios then became a hospitable host and not just a “face” in the street. He began to show his unexpected guests around the village and told us many interesting things about it.

The church in question turned out to be rather young — only 15 years old. But the story of its erection is one which sparks curiosity, spanning back over the centuries… It was built on the foundations of a previous church which was dismantled. In the words of Andreas, it couldn’t be distinguished for its exceptional beauty. In turn, that church “had a foothold” in this place for a long time: the ancient home of worship, which formerly stood here, collapsed out of decrepitude, and the “powers that were” at the time — the Ottoman-Turks — conceived the idea to raise a mosque instead of a Christian church.

“…that the conquerors had decided to build their own house of worship, in place of our church, we indigenous folk discovered entirely by accident: only from female conversations between Greek and Turkish women… Our village, after all, had been Christian from the beginning, and so as not to allow this plan to come into fruition, the local men built a new church, albeit not the most beautiful of sorts, literally over a single night. Can you imagine that?

Anyway, very recently, around 15 years ago, we decided to complete the construction of the new church. When preparations were underway, the fellow villagers appealed to the metropolitan with a request: to give permission to examine the old church, to uncover the layer of plastering which covered it and find out whether it was of historical and cultural value. After reviewing the results, the metropolitan said: build a new one!

Construction was sponsored by my friend Andreas Hadjiyannis — a native to Akaki and well-known Cypriot shipowner, as well as the president of their Association. Upon the metropolitan’s recommendation, the roof tiling was chosen and laid in the style of the other buildings surrounding the church.

The wall paintings were done by a Russian monk Amvrossi and his assistant. He also crafted icons — both for the church and the iconostasis — and created the artwork for the Royal Gates. You can see all this here. Amvrossi has yet to finish his work and so comes here from Skouriotissa, a beautiful place which we love to visit, lying on the way from Kalopanagiotis to Kykkos. The monastery of St. Seraphim of Sarov is located there [1].

The marble for the iconostasis was shipped over from Penteli in Greece [since the earliest times, the local mountain Pentelikon has been renowned for its marble deposits, which were partly used to construct the Acropolis of Athens, — edited by E. K-T]. The carver was a French craftsman”.

Andreas went on:

“Our church is dedicated to the miracle of the Archangel, concerning the salvation of a church in Phrygia (now in Turkish territory) from the machinations of pagans, who had directed waters from two rivers towards the building, hoping to flood it. Archippus of Herotop, a local righteous man, prayed to God to save the church. Having answered the man's prayers, God sent forth the Archangel Michael, who with a strike of his rod, opened a crevice in the earth, into which the stormy waters then surged. From that moment, the town was known as Honaz, meaning “hole” — this instance is featured on our church icon “Miracle in Honaz”… You know, this is actually a real place, where today you can witness a rather strange phenomenon: the river sharply disappears downwards underground, only then to surface in another spot”.

We entered the church, and it was simply breathtaking. Magnificent frescos on light blue backgrounds covered the whole surface of the arch, walls and niches in the church. On the walls, you can see scenes from the Resurrection of Lazarus, the Entrance of God into Jerusalem, the Assumption of the Virgin and others. The semicircular apse in the altar section features an image of the Virgin Hodegetria.

There is also a rather small (one layer), white iconostasis, expertly carved from marble, which is incredibly impressive: you’re hardly likely to see anything similar in the province!

The splendid craftsmanship of the icons housed inside is just as striking.

-

Having noticed our genuine interest in the church’s history, Andreas offered to take us to “a couple more exciting places”. How could we refuse?!

We took a seat in his jeep and raced out of the centre. This time, after returning to the main road leading to Troodos, we crossed it…

By this point, we’d already had the opportunity to observe the life of a farmer in Akaki. They lived in small, most often single-floor bungalows (each had its own agricultural technology and various worker’s “accessories”: trailers, ploughs, crop-sowing machines), all surrounded by gardens, cultivated fields and olive groves. Pastoral Akaki was all the more unfolding itself before us; the mighty Kyrenia ridge was in the backdrop, seemingly so close to where we were standing.

Another noticeable change was in the villagers’ transport. Now, instead of the routine “Mercs” and “Hondas” which we'd encountered in the centre, we began to come across only Fordson and Massey Ferguson tractors. The locals (strong and muscular men), with no less spirit, cleaved their way around the village in them.

We drove on and on, then came off the main road a little later and went along a small, old (likely, from Venetian times) stone bridge, leading to one of the highways. For some reason, a strange feeling arose here from within: as though the unusually narrow roadbed was somewhat… ribbed. It turned out that we were now journeying along a buried railway track — the only one on the island — which, for a short time, had once connected Nicosia and the surrounding villages with Ammochostos (Famagusta).

Interesting Spot — 1: An Ancient Roman Settlement

By no means, of course, had we been expecting to see this stunning sight amid the fields — an archaeological site discovered very recently, in January 2017, hidden amongst the cultivated fields and fruit groves, on the spot of an ancient settlement.

Research here is led by the Republic of Cyprus Department of Antiquities, who assume that the villa of a well-off family was once located here (the floors of the main build are covered with pebble mosaics, which somewhat reminded me of the mosaic techniques used to craft the flooring for some monuments of architecture in Paphos). Today, the spot is fenced off and guarded, while the site is actively under investigation and intruders are not welcome. It’s still possible, however, to walk around and make out what’s inside the fencing, maybe to even take a picture.

This scientific discovery hasn’t gone unnoticed by global society, including the BBC, who in «Cyprus reveals rare Roman horse race mosaic in Akaki» (from 26th January 2017) announced the following:

“A rare mosaic was discovered within the limits of Akaki village, depicting a racer in a chariot. It dates back to the 4th century. This 26 metre (in length) image was probably located in a villa belonging to representatives of the aristocracy.

The excavation is led by archaeologist Fryni Hadjichristofi”.

Our next destination was a fantastic landmark: I suspect that without our “guide”, we most likely wouldn’t have been able to find it.

Interesting Spot — 2: Tower of the Franks

… Or what remains of it. After returning from the excavation and “diving” once again into the now recognisable depths of old Akaki, we pushed on a little further, continuing along Ionni Kontou Street. We pulled over by one of the street residences located on a hillside, their imposing forms towering considerably high over the road below. In the garden of a standard old home, we saw something breathtaking — there was an ancient fortified structure, known by the name “the Tower of the Franks”. Andreas had even agreed with the “tower’s owners” (a joke!) that we could make a short visit to their plot, for research purposes. So, after ascending into the old garden, we were able to inspect what was once a defensive structure from the Frankish era.

The tower was, in fact, incredibly noteworthy: it was round in shape, crafted from large limestones. The foundations had been constructed with massive grey boulders (cobbles); the inner surface of its walls was thickly coated with a lime compound.

The “interior” either had some narrow alcoves on the walls or they were the remnants of a spiral staircase. As for the size: the walls were around 1 metre thick, with the foundation’s diameter close to 6 metres. The height, evidently, was no more than 8 metres. There were stone embrasures located on different levels (maybe, along the spiral staircase). Solid masonry still impresses to this day!

After saying bye to our guide and thanking him for politely taking part and helping in our “expedition”, we returned to the main square of Akaki, where the main village church was aptly located.

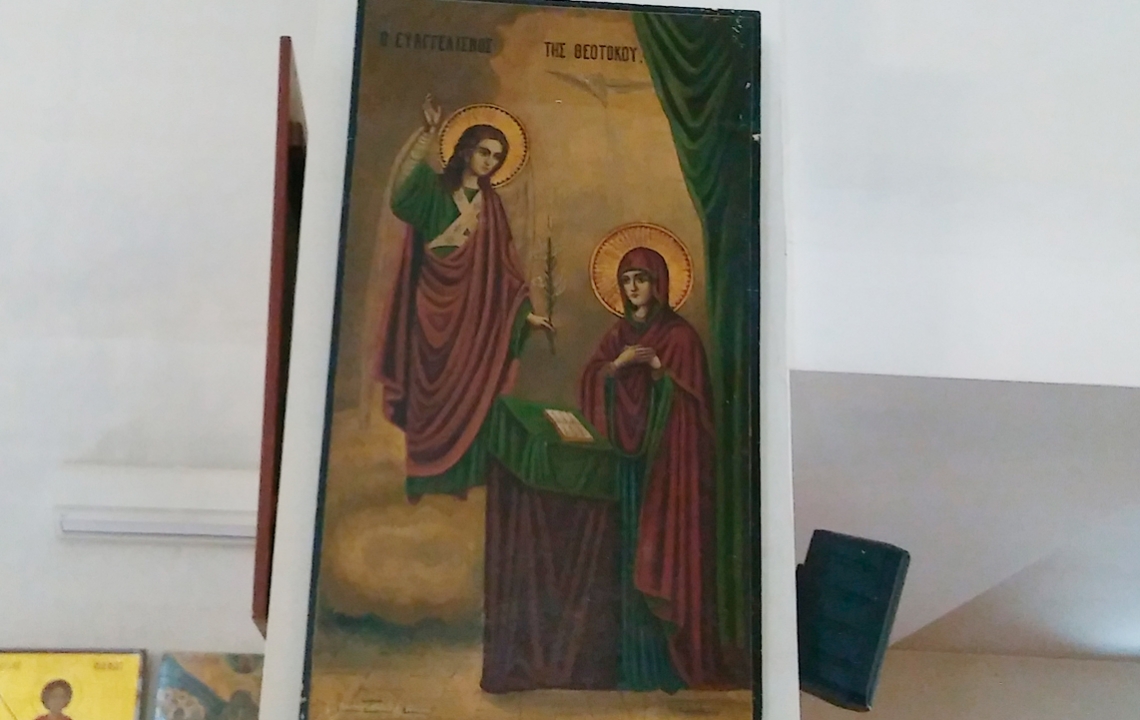

Panagia Chryseleousa looks rather new from the outside — a typical occurrence for many Cypriot villages. However, after entering the interior, past the magnificent dome painting with an image of Pantocratos (in all likelihood, this was the work of the very same Amvrossi) and also the three-tiered, carved iconostasis, you will, no doubt, notice the multitude of icons [2] from two local schools of icon painting: old and new.

The old local school (I’ve seen icons crafted in this traditional style right up to the mid-1970s) is distinguished by its narrative (with elements of landscape) as well as a hint to the volume and provincial manner of the imagery: for instance, Agios Andreas. The sky blue backgrounds are the main recognisable trait. As a rule, the icons are contemporary, crafted on a golden background. In both instances, the halos of the saints may have metallic inlays, indeed fashioned with the use of different techniques.

It’s worth having a look around once you’ve exited the church: the cobbled square has been visibly modernised, with the surroundings kept in good shape. There’s even a small public garden with a playground and relaxation benches. Opposite the church, you can see the modern building of the local justice, and a little to the side, across the road, a local coffee shop. Regardless of the time of day, there are always visitors here…

Kafenion — you’ve come across them rather often: even in the newest quarters of Cyprus' big cities. Traditionally, however, this was an institute with a long-standing history, intended for public life and the succession of generations. It has preserved its special significance, in particular, amongst rural localities.

As such, not one main square, from any of the villages in Cyprus, can get by without one of these establishments: local coffee shops are a focal point for men’s lives and the spot most visited by the male section of the population. They somewhat symbolise the transfer of worldly wisdom and community experience to the younger generation… People of an elderly age gather here to “relax the mind” in the pleasant company of those the same age: to discuss local events and global news, to play a set of backgammon and of course, to take their time in drinking a potent and refreshing “kipriakes”… As for young men and lads, they often call in here: to meet their neighbours in the evenings, after work or study, or to listen to the sensible advice of their elderly peers.

Frequenters to Kafenions are usually offered coffee, an assortment of fizzy drinks and simple snacks.

Curiously, from the other side of the church, opposite the justice building, there is another, younger and not so conservative “club” establishment: cafe-bar "Apla kai Oreia". On a warm evening, the noise of a football match would carry outside, while the entrance was crowded with excited supporters, both male and female.

Before our actual departure from Akaki, we did a small “lap of honour” around the central part. In the village quarter adjacent to the Church of the Virgin (at the intersection of Michalakis Savvas and Platonos Street), we discovered a single-storey, whitewashed, mosque building, albeit without the customary minaret. The rectangular build could only be distinguished from the neighbouring residences by a small portico with two columns, as well as an arched aperture — such shaping of the “arch” was used mainly for construction in the Gothic age, so the building was ancient.

-

The remaining landmarks are for when you have acquaintances in Akaki, or you simply live somewhere nearby, meaning you’ll find time to visit here once more:

Akaki River [3] (listed on the map as a continuation of the Serraxis, often noted under the name same) — this is one of the most beautiful sights in the village. In the winter months, the riverbed is full, and according to specific data, in certain places, the width reaches up to hundreds of metres. Interestingly, during the thawing season, a significant volume of pebbles and other stones is carried down from the mountains. These stones were traditionally used in construction.

Water Mills. The remains of several lie on the village territory, thanks to the lands here being replete with water (surface and subsoil waters). The most famous of them is the Watermill of Tsigis, which is known to have been in operation till 1928; another well-known construct is the so-called “Osman Bey mill”, which was built later and recently underwent reconstruction. It is worth note due to there being three whole mills inside: they were used for manufacturing olive oil, cotton-cleaning and producing cattle feed.

The Hodjia Water Mill Museum was opened here.

Underground wells. Within the limits of Akaki, there are several “wells” (essentially water pockets), which form a whole chain known as “lagumia”… According to the researcher Manoloudis, the overall length of these wells totals 17km, with their depth sometimes reaching 30-32 metres! The villagers used shovels and arable machinery to dig up these underground reservoirs.

It’s also worth mentioning:

The Chapel of Saint Barbara (Agia Barbara is rather new: it was built between 1940 and 1950, using the donations of a local farmer and shepherd Michalis Kyriakou, nicknamed “Avramis” who had requested holy intercession for his herd of sheep. The Tower of the Franks stands nearby.

The Church of the Metamorphosis-tou-Sotiros (The Transformations of the Lord) — a simple, single-nave build, with a bell-tower and small, carved iconostasis. It was built using donations from several families and consecrated in the presence of the Kyrenian metropolitan Kirill II. The icon of the ‘Transformation’ is now situated in the main village church.

The church and chapel of St. Barbara both stand on Mana-ton-paidion street.

-

After exiting Akaki, we headed to a neighbouring village, lying 5 km in the direction of Troodos; curiosity and the excitement of making new discoveries had no doubt led us here.

Peristerona

A village near to Akaki (along both river banks, like Peristerona), lying 32 km to the west of Nicosia, by the Troodos foothills, at a height of 250m above sea level. Within Peristerona's limits, there is a magnificent sandstone bridge with three arches, which connects both parts of the village. Today here reside no less than 2200 people. Like in Akaki, the village, by and large, grows citrus fruits, as well as various vegetables, wheat, olives and almonds.

Bear in mind: there is a buffer zone near to the residential quarters and amidst the fields, which it’d be wise not to overstep.

The name Peristerona [4] originates from “peristeri” meaning “pigeon” in Greek. Thanks to the location and favourable development in its agricultural industry, the village is constantly prospering and increasing in size, especially in the last few years.

Throughout the events of 1973, the village suffered its share of losses and victims: three people were killed, and three went missing without a trace. A monument dedicated to them was opened several years ago (at the entrance to Peristerona).

For more detailed information about these people, as well as others who went missing during the Turkish occupation, please see here: www.missing-cy.org. The ultimate fates of some are already common knowledge, while the search for others is still undergoing. Though their families, loved ones and friends have now grown old, they have never forgotten about them…

-

Having crossed the bridge over the riverbed, at times seething, but now almost completely dried up, we reached the centre of the “Pigeon” village. The main temple is aptly located here — but we will speak about it a little later, as well as a couple of coffee shops and a very convenient parking area.

Peristerona immediately struck us with its, at first glance, small size, compact layout and general cosiness ! The village lies on hilly terrain and is therefore rather scenic, even picturesque. It was once a “mixed” settlement, home to natives of both the Greek and Turkish community. A symbol of their once (until 1963-64) peaceful coexistence, as they like to say in many tourist guides, is the close vicinity of the Orthodox church and mosque. An issue of stamps with their image was even dedicated to this theme.

Nowadays, in comparison with the somewhat modern and in rural terms, “dynamically developing” Akaki, it’s tranquil here in the old centre… This spot is appealing, namely for its historicism: the street developments may also be exciting and to the taste of many admirers of ruralism.

So, we exited onto the square: it was lovely here in the evening, both because of its simplicity and how well it has been taken care of. The cobbled surface echoed our steps, and the floor lighting, fitted into the paving, snatched the old walls out of the thickening twilight…

An evening service was coming to an end in the church. All the fires were still burning, and a few elderly villagers were exiting together in a group, like dark silhouettes melting away somewhere into the narrow lanes and ink-black shadows of their gardens.

We went closer.

Nearby the river stands the Church of St. Varnava and Illarion. Dating back to the 12th century (according to some sources, the 10th century), it’s a five-domed build with a cruciform layout — a great rarity for Cyprus. Aside from this, inside the Byzantine church — now a UNESCO protected site (introduced to the list in 2004, as number 1874) — there are several old icons of the Saviour, crafted in the 16th century. The interior walls of the church are covered with frescos.

The stone foundations, uncovered by archaeologists during examinations of the surrounding locality, eloquently testify to there once having been a church here, most likely from the early Christian period.

To the right, you can see a two-storey house with a mosaic image of a swan on a facade — the local governing body and centre of culture for the village. Its activities are supported by the episcopate of Morphou, as well as the UN Development Programmer and USAid.

Further up along the street lies the mosque mentioned earlier. It’s an old (bordering between 18th and 19th century, Ottoman rule), albeit small, stunning building, situated to the south of the Orthodox Church. The mosque is now closed for visitors and has been abandoned for a rather long time: the last time people prayed here was obviously in the 1970s. Located at an elevated height, it is still appealing with its flying silhouette, stained glass windows and stucco decor.

It’s well known to historians as a rebuilt gothic church from the Lusignan era.

There is also the chapel of Agia Varvara in Peristerona, the construction of which dates back to the 16th century.

-

The village embankment, albeit rather spacious, is deserted amidst the yellow circles of lamplight. You’re able to breathe in the fresh, humid evening air and take an unhurried glance over the surroundings: a broad, stony channel, beyond which the other side of Peristerona stretches out in a darkening mass. If you glance to the left — a slow, tired caravan of cars drag themselves one by one to the capital, on the brightly lit Leoforos Nikosias highway.

We are well aware of the moments the people sitting in these cars have experienced this weekend; moments which have enriched their lives and we understand them all too well. Our own journey and the discoveries we’ve made on this day have also become special… which is what we wish for you!

However, let’s carry on…

The village infrastructure is sufficiently well developed: there are several bars and taverns where you can order local cuisine. In theory, there’s always the possibility to rent accommodation nearby, but you’ll need to clarify on corresponding websites whether offers are still valid.

That being said, it’s far more convenient and reliable, in my eyes, to find suitable accommodation in any of the country’s cities (in Nicosia too). Then, after renting a car or deciding on a bus route, which it’s essential you do with the timetable on www.cyprusbybus.com, you can set off on an insightful trip.

It’s worth paying attention, for instance, to this site: www.cyprusvillasrent.com and others.

The houses in Peristerona used to be built small: from brick or, as they did in times of old, mud-brick (dried briquettes made of clay and mixed with chopped straw. So, the traditional developments consisted mainly of three-storey bungalows, which together with the garden and courtyard, often surrounded these concealed, stone or plastered brick walls.

-

If you’ve chosen to visit Peristerona (rather like any other traditional Cypriot village) on one of the days in late December – early January, then you’ll definitely notice the olive branches attached to doors or stuck to doorposts. Are you wondering why they are there?

According to folk superstitions spread amongst the Greeks, Turks and people of the Balkan states, olive branches are capable of protecting the home from evil and driving away underground spirits known as «καλλικάντζαρος». They sometimes surface, in the company of their own kind, on the nights between Christmas and the Epiphany (25th December – 6th January).

In general, traditional folklore says these malevolent spirits are busy with other matters: in their underground kingdom, they are gathered as a group, focused solely on trying to cut down the World Tree. When their wicked deed is near complete, Christmas arrives, and distracted by the opportunity to frolic with the lives of man, on a “one-time-basis”, as they say, they forget everything else and rush upwards to the surface.

The Tree heals in this time, becoming whole and mighty once again, whereas people, on the other hand, need to be on their guard. They say there are alternative ways of frightening away the evil. Leaving a colander on the threshold of your home at this time, for example, is considered to be a “very useful” method: the night beasts don’t know how to count to more than two, after all, three — the Trinity — is a sacred number, the name of which kills these mischievous goblins. However, if this isn’t reason enough for you, then every night in succession, it’s worth keeping a fire burning in the hearth: so that your hot chimney doesn’t let any unwanted guests into your home… The especially decisive, as they say, are ready for even the most extreme measures: when it gets dark, they burn old leather boots in the fireplace, as the repulsive smell of burning chases the evil away (as is the case, evidently, with any nuisance guests).

Furthermore: in the past, children born on these “difficult” days were considered to have required more attention than others. Therefore, items such as a bundle of garlic or a batch of straw etc. were placed nearby to protect them.

Good news for those born on Saturdays: according to the same local superstitions, not only could these “chosen ones” see (in all their beauty) the creations of the night but were even able to, if they wished so, fearlessly communicate with them.

And that’s village life — anything but dull! [5]

-

We will still venture out for walks in the villages and hamlets of Cyprus, many of which, across several centuries, were historically mixed, based on the character of their population. For example, by 1891, 43 per cent (this totalled 346 settlements) had permanent residents from both communities.

We would, therefore, like to tell you about this peculiarity in the island's history, culture and inter-communal relations.

For several years, the fate of mixed settlements in Cyprus, the study of their characteristics and assessing the population’s quality of life, as well as their model of coexistence — this has been the subject for a series of in-depth scientific research projects, conferences, seminars and other events. Now we can briefly examine the topic in question, using Peristerona as an example.

Today’s elderly residents recall how, even in spite of various historical events, people always got on with neighbours from other communities. However, it would be wise not to forget that varying disagreements, often over extremely religious, cultural and other issues, still remained.

The main event which significantly influenced demarcation was the 1821 Greek Revolution against the yolk of the Ottoman Empire. Besides, a negative response, which strengthened revolutionary sentiments in Cypriot society, had been incited by the repressive attitude of the Turkish government towards the Orthodox clergy. This was demonstrated in 1824, when the leaders of the island’s churches (the archbishop and metropolitans), whom the Turks had suspected of supporting the idea for a Greek revolution [6] were executed.

In the early 20th century, growth in Greek nationalism in Greece and Cyprus followed, as well as increasing assimilation of Greek-Cypriots for an “all-Greek unification or a Great Greece”. Consequently, the conflict between Greece and Turkey exacerbated. And so, the years between the two World wars saw a sharp drop in the number of mixed villages on the island — down to 36% (only 252 settlements, according to data from 1931).

Fresh drops in the number of settlements — where people had been living at peace with their neighbours, regardless of the traditions and cultures which they honoured, or the faith which they practised — were observed twice more: in 1960, as a result of “enosis” sentiments — down to 18%; and finally, in 1970 — down to 10%.

Intercommunal coexistence, which was present in Peristerona, is a fascinating structure in society and has been noted by researchers of this topic. The Cypriot-Turks who used to reside here were, by and large, landowners, while the Greeks often became hired workers on arable croplands. As for administrative matters, authority was divided equally here (we can observe a similar example in modern-day Pyla). Each community was appointed a mukhtar — a notary (also the local administrator); and a bi-communal committee regulated the usage of water from the River Peristerona.

Social interaction between people was profound and significant. It occurred both through the lens of professional contacts and personal friendships, as well as the joint organisation and participation in local celebrations and other events, which were necessary to members of society.

Aside from this, living quarters were mixed, and members of the community were not isolated in their groupings.

As we approach the end of today’s stroll, we will cite a quote from a traveller about the places here. Fergus Murray (an American traveller-blogger, writer and artist) shares his impressions in his blog:

"One of the villages I've liked the most during my brief travels in Cyprus is Peristerona. The village has a welcoming feel… after the brash suburbs of Nicosia. It also feels alive, vibrant even, compared to the locked-up villages in the high winter hills.

On the road from Nicosia, it is preceded by the smaller village of Akaki, sited on another river…flowing down from the northern Troodos mountains.

There is a series of channels that takes waters from the Akaki through the village streets, which I found charming but difficult to photograph" [7].

How to get there:

By car: from Nicosia — along the Nicosia — Troodos highway (B1, continuing on the B9 and then the A9). After it has ended, follow the signs again to exit onto the B9 (here this is Leoforos Nicosias street, which connects the villages by the Troodos foothills) and carry straight on until the signposted turn-off to the left. Further on — ahead to the village centre.

So, we first reach Akaki, and then exit again onto the B9, heading towards the Troodos — until the next turn-off to the left — for Peristerona. It will take you 35 to 40 minutes respectively to get there from Nicosia.

By bus: the 400 and 404 go from Nicosia, for more details, see here.

Sources:

Authentic Cyprus: discover it... (Cyprus Tourism Organisation), 2007. Read here.

Giorgos Karouzis, Strolling Around Cyprus, Nicosia, (City and District), Nicosia 2002

Georgios M. Manoloudes, “Akaki — History and Tradition”, 2001

And also the websites: www.cyprusland.net, www.ksakaki.com.

Information and Contacts:

Address of the Justice building in Akaki: Archbishop Makariou Street – 3, 55

Tel: (+357) 22822351

Stay with us and see you next time!

[1] The first stone for the foundation of the future construct was placed on the 2nd January 2010, in memory of St. Seraphima. See here for more details.

[2] A short history: As is well known, the 11th century was marked as the heyday of religious art in Cyprus: a multitude of churches were raised, the walls of which were decorated with frescoes; numerous icons were created… What’s worth noting is since that time, the tradition of fashioning icons, like all works carried out in churches, has been preserved to this day by local craftsmen.

[3] Moreover, 26 km to the south-west of Nicosia, the river water from Akaki supplies the local reservoir, on which the Malunta dam has been built, near to the village of Klirou.

[4] There are two villages with the same name on the island: one is located in the neighbourhoods of Paphos, the other in the Famagusta region.

[6] Under the leadership of the then Archbishop Kyprianou, a significant number of Greek-Cypriots are well known to have attached themselves to the revolutionary society “Filiki Eteria” (“The Society of Friends” was created in 1814 by ethnic Greeks in the city of Odessa, part of the Russian Empire). Their leader Alexander Ypsilantis (1792-1828), who consequently became a national hero, wrote a letter in which he requested an answer to the following question: will the Cypriots support the rebellion. The archbishop replied that there would most definitely be support, including of the material and spiritual sort… Thus, the Turkish administration had not aimlessly begun to fret about their position on the island. The conspirators were informed on, to governor Mahmed Kuchku and on the 9th June 1821, by his decree, the higher clergy, as well as other priests and peaceful folk (around 500), arrived in Nicosia. They were all met with a bloody reprisal and executed over four days. A marble mausoleum (1930) stands in the courtyard of Faneromeni church in the Old City, to which the remains of Archbishop Kyprianos, three metropolitans and eminent Cypriot citizens from the ranks of those executed, were transferred from the church.