The Cyprus Archaeological Museum (also known as the Cyprus Museum) — is the oldest and largest archeological museum in the country. It houses an expansive and unique collection of antiquities: various artifacts found over centuries of archaeological research.

These quiet halls house the entire history of Cyprus: thousands of years, numerous civilizations that emerged and disappeared, different cultures, epochs and people who defined the island’s history and traditions.

Part 1. Museum

The website of the Department of Antiquities states that the Museum was founded in 1888 during the British period and at the request of the local population. A public petition was filed with the Consulate in response to the illegal excavation work that was taking place on the island and the smuggling of numerous historical valuables out of the country. One such «black archeologist», who was particularly zealous in his work was an American ambassador and scientist Luigi Palma di Cesnola, who managed to smuggle out more than 35 thousand artifacts. Many of these artifacts were subsequently lost or damaged during transportation. Those that survived are now part of the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

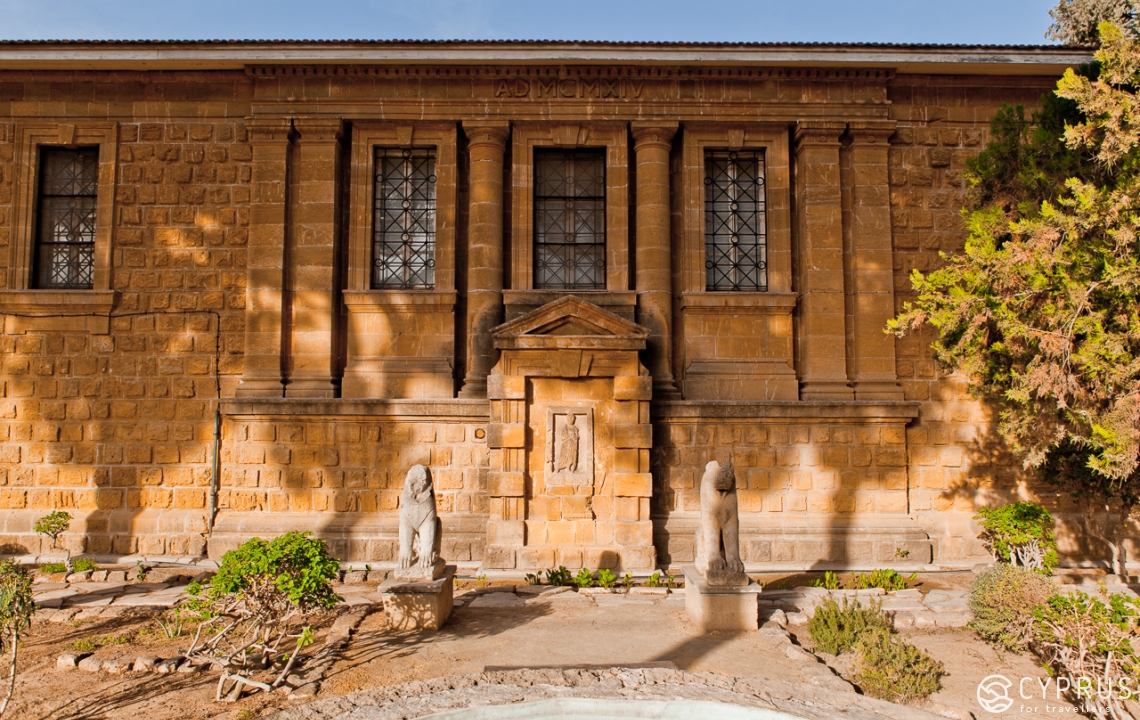

The first law on archeology was passed in Cyprus in 1905. It laid the foundation for the science of archeology in the country. In the beginning the Museum survived thanks to the support from numerous donors and sponsors. It was first housed inside one of the local government buildings, but in 1889 the Museum was moved to a separate building in the Old Town (located on what was once known as Victoria Street and which later became Salahi Sevkey Street — part of Northern Nicosia occupied by Turkey). The construction of the building that houses the Museum today took place between 1908-1912 and was dedicated to the memory of Queen Victoria (a marble plaque and a royal monogram hang over the entrance to reflect this dedication). The construction process was overseen by G.E. Jeffrey, who was also the museum curator at the time. G. Balanos (member of the Athens Architectural Society) was the leading architect. In 1961 another building was annexed to the Museum to store artifacts and house additional galleries.

Immediately following its opening, numerous archaeological findings, made primarily by the British archaeologists on the island, began flooding the Museum. The first complete catalogue of all of the items was published in 1899. The collection was significantly expanded during the first large-scale archaeological expedition conducted by Swedish scientists under the supervision of Professor Einar Gjerstad in 1927-1931.

As more and more artifacts continued to arrive at the Museum, its curators realized the need for a larger space that would accommodate the growing collection. In 1935 a piece of legislation was passed that led to the creation of the Department of Antiquities. This, in turn, allowed the Museum to continue its work as a research institution and an exhibition space. By this time Cypriot archaeologists had done a lot more research, which uncovered some of the earliest periods of Cypriot history that helped to recreate the island’s evolution from the very beginning.

Following Cyprus’s independence in 1960, the country’s archaeological society saw a period of prosperity after it was able to reassert itself in the eyes of the international community of archeologists and presented important research.

The present exhibition is housed in 14 halls and covers centuries of the island’s history. The objects are displayed in a chronological order from the prehistoric period (pre-pottery neolithic B) to the early Byzantine period.

The Museum is also home to a library, archives and research facilities. In recent years the collection has been partially decentralized and some of the objects were moved to other museums in Cyprus.

Part 2. The halls

The exhibition halls display antique remains of the island’s material heritage: terracotta ceramics, objects made of bronze and colored glass, mycenaean ceramics, carved stone, antique coins and jewelry and many other are items that reflect the evolution of artistic styles. Today we are going to visit the Museum and share our experience with you.

On the right hand side of the first hall you will find a series of objects (tools, stone statues and hars), which represent the earliest traces of human existence on the island. The left hand side of the hall is dedicated to the Chalcolithic period, when stone jars existed alongside handmade ceramics. Other items displayed on the left side are picrolite figures.

The most well-known items on display:

The display case with anthropomorphic figures (to the left of the entrance) features the famous Idol of Pomos — an example of prehistoric sculpture (circa the 30th century). The cross-shaped statue was found near the village of Pomos, near Paphos and symbolizes fertility. Today it is one of the main symbols of Cyprus and is depicted on Cypriot euro coins of 1 and 2 euro.

There is another sculpture of the same size and shape, but featuring two idols intersecting each other and forming a cross. This is known as a «double deity» — another ancient cult symbol.

This type of cross-shaped figures have been discovered in numerous Chalcolithic settlements in Cyprus. It is possible that many of them were worn on the neck as amulets.

Numerous white clay ceramic remains displayed in the first hall also belong to the Chalcolithic period (3500-2300 BC).

Keep in mind that people did not have the potter’s wheel at the time (it was invented at some point between 4000 and 3000 BC) and the shape of sculptures from that time period reflect this fact (pieces of clay were either stuck on top of each other or applied using a spiral method). Ceramic statues made with white clay have also survived to this day. The following two halls represent the evolution of ceramics production and its use. The second hall is dedicated to the large collection of early bronze ceramics (2400-2000 BC). The third hall is dedicated to the development of ceramics starting from the middle of the Bronze Age (1900-1600 BC) until the Roman period.

The exhibition features objects made locally, which represent the Cypriot tradition of ceramics production, but also foreign-made Mycenaean, Phoenician, Attic ceramics from different time periods.

The first few halls display objects from different time periods that were discovered during various archaeological digs in Khirokitia, Kalavasos, Cape Apostolos Andreas, Erimi, Kouklia, Petra tou Romiou, Sotira, Troulloi, Kissonerga and Parekklisia.

It is very interesting to see in person what those archaeologists have uncovered: jewelry (numerous necklaces and fragments of earrings) made of seashells and gemstones; flint and steel, razors and other tools and their fragments made from dense types of rock such as flint and volcanic glass; flat rocks with indentation used to grind grains, anthropomorphic figures and various pitchers.

There is a long description available in Greek and English that talks about the archaeological research that uncovered remains of the Chalcolithic period as well as a map of the areas that pertain to it.

All of the objects are accentuated with dim lighting, which not only allows the viewer to see their details, but also ensures that the artifacts are carefully preserved.

The next hall continues to explore the artifacts uncovered during archeological research in Troulloi, Sotira and Khirokitia that belong to the Pottery Neolithic period (4500-4000 BC). The main focus of this hall is again ceramics: the technology and its application. Most of the ceramics in this hall were made of red clay. The geometric ornaments cover large areas of the vessels, vases and pitchers. You can see the origins of sculpture: there are entire scenes and stories molded on some of the round-shaped jars. The central display case contains a multi-bodied model made of clay that was discovered in Vounous Necropolis (2500-1900 BC). This is how we gradually transition into the Bronze period of Cypriot history.

The Bronze Age (2500-1050 BC) first saw the arrival of Anatolians in Cyprus (circa 2400 BC), then residents of Crete and Mikines. Greek colonists (the most powerful of whom were King Teucer and King Agapenor, who founded Salamis and Paphos) brought with them language, art and religion. Cyprus, which was then known as Alashiya, had the highest occurrence of copper and bronze in the eastern Mediterranean region. Ships that departed from Alashiya heading west and east were loaded with metal sheets shaped like cow skins that weighed 25 and sometimes even 40 kilograms.

Among the many statues showcased in this part of the Museum, you will come across a bronze-made, horned deity wearing a helmet. The deity stands on top of one of the «cow skins».

These early ceramic items were made for completely different purposes. Pottery masters from this time period demonstrate a more confident approach to sculpting by going beyond simple decor elements and making stand-alone sculptures. Most of the objects on display come from the Vounous Necropolis.

Please note that most of the objects in this hall (as well the ones to follow), which are made of red clay, are actually black in color. This is because they were probably scorched by the fire during one of the cataclysms of the past (e.g. a number of earthquakes shook the country at the end of the Bronze Age). The only exceptions are the smoked ceramic and oil lamps, which became dark due to long use.

We are now in the spacious hall that displays white clay ceramics. You can tell that locally produced white clay items are smaller in size than those brought from Mikines. Following the collapse of their civilization at the end of the 12th century BC the Mycenaeans came to Cyprus en masse and brought elements of their culture. Hence the changes in «design»: we see cups and bowls with handles, smaller jars (possibly used to store rose water and perfume). Looking at this we can conclude that earlier periods were characterized by smaller pottery that was less refined in detailing, whereas the «more mature» pottery of the Mycenaean civilization reflect a more confident approach to sculpting items of different sizes, such as large and more massive amphoras, pots, pitchers and smaller and items like wine cups and perfume bottles with sophisticated detailing.

Images of bulls and rams begin to make a frequent appearance alongside human figures. You can also notice a new type of ornamentation — a combination of geometric patterns and a stylized «wave». These are characteristics of the middle (1900-1600 BC) and the end of the Bronze Age (1650-1050 BC).

And so the metal sheets were exported out of Cyprus in exchange for imports from Syria and Egypt, such as vases, pottery and objects made of alabaster.

In the center of the hall is a cross-shaped display case containing pottery imported from Syria (13th century BC). These are candle-holders, smoking pipes, vials that resemble expensive jewelry. The glazed ceramics feature a «greenstone» effect (incidentally, this type of technology was used in ancient Chinese and Egyptian pottery) and new motifs: zoomorphic figures (e.g. monkeys) have replaced anthropomorphic characters. The bottom shelf of the display case carries on the «Mycenaean theme» displaying white ceramics with traditional red striped patterns.

Background information is available for those who want to learn about this period in Cypriot history, its characteristics and findings.

The latter part of the Bronze Age features ceramics that look like they were made of metal. The shape and style of decoration is different too: it is applied in a braid-like manner. Smoking pipes and lamps have a more sophisticated shape and often include images of animals.

One of the following display cases (1650-1200 BC) also contains examples of imported ceramics made with white and red clay in Syria, Palestine and Iran. These ceramics were adorned with realistic images of animals, birds and fish. Another display case contains examples of a proto-geometric style (1100-1050 BC): geometric decor and ornate ceramics.

The other side of the hall is dedicated entirely to the Mycenaean period that is characterized by larger objects. Some of the scenes pictured on the red clay objects allow us to better picture this time period.

The quality of the restoration work is particularly noteworthy — some of the objects have been literally pieced together.

The following display cases contain objects from the three phases of the Cypriot geometric period. Most of these objects feature scenes with animals not only on the outside, but also on the inside. There are scenes of bulls, rams, monkeys (Asian influence) and snakes drinking from a water hole. Some display cases contain particularly large amphoras from the 8th-7th centuries BC. Walk around them (there is only four amphoras) and explore the images from mythology, rituals and celebrations. The exhibition invites you to learn about culture and mythology, but also household life of that time period.

One thing to keep in mind: two of the four amphoras are covered with geometric patterns, while the others have a floral pattern (lotuses — an Egyptian influence) and are generally more decorated and feature what looks like a mosaic.

The following hall is dedicated to the Iron Age (1050-475 BC). After a number of prosperous cities were destroyed in a series of cataclysms, Cyprus entered a completely new period of its history. In approximately 900 BC the island saw the arrival of the Phoenicians, who founded a strong state with Kition (now known as Larnaca) as its center. Then came a period of the Assyrians, who left the famous Sargon II stele (now located in the Berlin Museum). The period between 8th-7th century BC is considered the golden era of Cyprus. The Assyrians were then replaced by the Egyptians, who were in turn followed by the Persians. All of these cultures brought something from their culture to Cyprus (material and spiritual).

We are now in the Hellenic hall (325-50 BC), where admirers of antiquity will recognize it by its signature red and black-figured ceramics (amphoras, smoking pipes, lamps and vessels). A reminder: black-figured pottery first emerged in the Corinth in the 7th century BC and was brought to Cyprus by ship. Later in the 5th century red-figured amphoras began to arrive from Athens.

Next is the Greco-Roman period (50 BC – 395 AD) with its unique sculptures exhibited out in the open, which doesn’t happen at any other museum that houses a collection of antiquities.

The pottery is different too: red clay objects are becoming more minimalist in details and the surface looks more polished. At the same time the sculptural detailing have been brought to perfection: the body of the jar features realistic scenes with animals and floral motifs, which give the object an entirely new look. Female-headed anthropomorphic figures are becoming more popular.

On the other side of the hall are objects of the classical period, which went through several stages of historical development that span a period of time between 475-400 BC. The pottery that represents this period is covered in schematic images of fish and appears like it was crafted in a more slipshod manner, which stands in sharp contrast to the the impeccable technique used to produce the sculptures we talked about before.

We even had our own «pseudoscientific» theory for it: these jars, which were certainly created by high-skilled craftsmen and decorated with various figures, must have been used to teach a young generation of ceramists. But who knows…

The classical period reached its peak in 400-325 BC. Ornamentation had by then become more simple. The same happened to the figures, which look more schematic. But these are not all the changes that the visitor should be able to notice. The chronology of the exhibited objects appears interrupted from time to time (this could be because of the constant updates taking place at the Museum).

One of the last display cases in this hall contains examples of imported ceramics (circa 8th-6th centuries BC). Look at the painstaking attention to detail on these objects. This pottery was brought to Cyprus from Rodos and Ionia.

Incidentally, Roodos pottery is characterized by very well-sculpted anthropomorphic figures. Ionic pottery, on the other hand, has simple shapes and a very minimalist design.

There is additional information available next to the displayed objects, in case you want to learn more about this time period and the different cultures that influenced it.

The following hall is dedicated to the East and the objects that came from that region. Terracotta male heads (7th-6th centuries BC) styled in a manner that was common in Assyria and Babylon: long hair held back with a band and thick curvy beards.

The next hall is sure to bring you true delight. It is home to one of the most «popular» display cases at the Museum.

The most incredible group of objects are the Iron Age (circa 700-525 BC) findings made by Swedish archaeologists in 1929 near an old sanctuary in Ayia Irini located in the north-east of Cyprus. Researchers came to this area under the aegis of the Museum after Father Procopius discovered a piece of a terracotta figure as he was working in the field near his church in Ayia Irini and brought the object to the Museum.

What they discovered was a sacrificial altar, surrounded by 2000 terracotta figures. At some point the sanctuary was destroyed by a flood, but its remains and the objects that it once housed were buried under a thick layer of sand. The figures vary in size: some are miniatures and others are gigantic. The faces also look different: some are carefully sculpted, while others are just rough depictions. Most of these figures are of soldiers (either riding a chariot or walking), others are priests wearing bull masks, and only two of the figures are female. There are some figures of bulls. And if you look closer, many (and possibly even all) figures had been painted.

When you watch them frozen in time, but still going on about their mysterious life, they begin to resemble the famous Terracotta Army of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China. The different size of the figures could be indicative of their different status. Some of them even have sheaths, which must have at some point contained real swords. This could be an army worshipping the god of war and (or) fertility and cattle production, which was called upon to protect the city against an attack.

The Museum of Cyprus houses only half of all of the discovered sculptures. The other half is located at the Museum of Antiquities of the Mediterranean and the Middle East (Medelhavsmuseet) in Stockholm. There are photographs of the archaeological dig and an explanatory text accompanying the display case.

We now enter the Sculptures Gallery of the Museum. This part of the Museum is dedicated to the way the Egyptians and the Assyrians had influenced classical sculpture in Cyprus. Archaic statues carved out of limestone were gradually replaced by marble-made works with Greek motifs and undertones.

The collection of these works has been on display for some time now. It feels like the figures surround the viewers, like they are «among us». This creates a feeling of being integrated into the work and its history. On the other hand, it is probably not very good for the objects. I think that the curators should take this collection more seriously and not simply rely on the sign that reads «Do not touch».

Let’s go back to the exhibition. Some of the sculptures were discovered in Tamassos (Nicosia region), including the assyrian objects, such as the «Figure of a bearded man» 510-450 BC. Most of the sculptures were made of limestone and terracotta. Some of the figures are female (such as the one holding a sacrificial animal, who could be the Greek Kibela, or the «Great Mother of Gods»).

In the center of the hall is a massive statue made of limestone (Likoniko, 500-480 BC) next to a group of figures standing on a pedestal made of the same material and decorated with lions.

Here is a figure of Zeus — also made of limestone. All the statues are dated from the 6th century BC. The walls are lined with mounted shelves that display small figures carved from the same stone (possibly something to do with a funeral ritual). Unfortunately, in this part of the Museum there is very little explanatory information on the objects on display, their use and history.

The sculptures that have survived to this day look almost completely white (the same color as the material that it was once made with), but if you look closer you will easily make out the subtle traces of pigment: red is more pronounced (it may have been the more resilient one) and is present on the clothing, beards and lips.

The last part of the hall contains either heads of antique sculptures (the marble-made male head and the female one with a crown — are particularly interesting) or Eastern statues of lions and Egyptian sphinxes. During the Greco-Roman period, which is known for its love of marble sculpture, most of the statues were made using local limestone (e.g. the surviving head of Alexander of Macedonia from the Hellenic Period (250-200 BC).

The most well-known objects of this time period:

The Statue of Aphrodite made with white marble (1st century BC) is a depiction of a goddess that came from water, but was also born in Cyprus. It is of Malaysian origin and was originally likened to Isida and Ishtar.

The marble statues on display in this hall are all quite small in size, whereas the limestone objects are all quite big.

The subsequent stage of Cypriot sculpture, or the Roman period, is on display in Hall 6, where most of the marble and bronze statues are located. In the center of the room is a bronze statue of Septimius Severus — it is considered a major work of art and there is an interesting story behind its acquisition.

Lucius Septimius Severus was a Roman emperor who ruled from 193-211. During his reign Cyprus witnessed the construction of many public buildings (e.g. the Soli Theater), an aqueduct from Salamis to Kythrea. Just like in many other Roman provinces, Cyprus too had an emperor’s cult, in which people worshiped the ruler alongside other local gods. Palea Paphos had an official cult of Septimius Severus alongside that of Aphrodite. There is also evidence (dated 3rd century) of an existence of a large church in Cyprus that is dedicated to Severus and his son Karakalle. The Statue of Septimus Severus is the only Roman period large bronze statue that has survived to this day in Cyprus. It is not known whether this is a church statue or just a monument. Unlike other sculptural depictions of Severus, this one shows the emperor nude. According to a number of researchers the position of the arms and hands indicates that the Emperor had once held a spear and a shield. The statue of the ruler was discovered in 1928 by a peasant who was working in the field near Kythrea (a village in the north of the island, which was once home to the kingdom of Hitri). The statue was quite damaged when it was first brought to the Museum — not so much by time as by the peasant himself, who was under the impression that it contained hidden treasures and tried to open it any which way he could. Thanks to his inquisitive mind and perseverance, the restoration process took years and it wasn’t until the year 1940 that the statue was finally exhibited.

Nearby is a series of photographs showing the restoration process. There is a fragment of Laokoon (an image of a snake). Please note that there is an original and a modern copy of the bronze «Head of a Young Man». The original had at one point suffered significant damage and the replica allows us to enjoy the work of art as it was intended.

The exhibition also includes a few male heads made of limestone and marble: Solus Sotirou (from Soli) and others. There is also an unusual rendition of Canopus that displays evidence of Egyptian influence: the egg-shaped water deity has a snake on his chest and a blossoming lotus on top.

This hall also has on display incredible realistic reclining marble figures of other water deities (from Salamis), a sleeping Eros (Paphos 3rd century) and even the dolphin-shaped base of a table.

The bronze hall contains three sections: the first one is dedicated to the use of bronze in everyday life (household tools) and the military (weaponry) the other section shows the use of bronze in commercial practices (tripods) and funeral ceremonies (the horned god of Engomi).

So, for example, the small mounted display case contains bronze figures that are associated with a period of time between Antiquity and the Classics (7th-5th century BC). The head of Zeus-Ammon is really quite elaborate and features a pair of set-in eyes and other silver elements (300-200 BC). The following display case is dedicated to the subject of military, among other things, and contains objects like spear-heads, bronze arrows, knives, farming tools, nails, etc.

On the opposite side is a series of bronze objects that were discovered in Engomi: miniature chariots, thrones, tables, stands, etc. These objects are so elaborately and realistically crafted that you can see each detail on them. There are also bronze hair accessories. But also different standing and reclining figures of people and animals that are not as elaborately crafted (Kalavasos and Pila region, 12th century BC). Have a look at the ancient scales and the weights that come with them (Maa village, 12th century BC). Hall 11 contains incredible findings made inside royal tombs in Salamina. Among these are a bed encrusted with ivory and stained glass, two thrones and a bronze boiler decorated with four busts of sirens and eight gryphons and placed on top of an iron tripod.

Other mounted and horizontal display cases contain cylinder seals from Egypt, Syria and Anatolia with accompanying photos of their impressions.

This part of the exhibit also contain Egyptian scarabs made of stone and glass, which were discovered in Ayia Irini Tetimenus (7th-6th century BC). The following case carries on the «Egyptian theme» by displaying amulets made with a paste that imitates the semi-precious green-stone and turquoise (these are pretty rare objects for Cyprus). The horizontal display case further down contains various kinds of relief decorations (late Bronze), fragments of ceramics and again: different seals and impressions.

Numismatists will definitely enjoy the collection of antique coins that represents all of the city-states that ever existed in Cyprus.

If you are somewhat overwhelmed with what you’ve seen so far, «take a break» by approaching the display case with various gold and silver jewelry from the Neolithic to the late Bronze Age (1650-1050 BC).

There is plenty to rest your gaze on: necklaces, rings, seal-rings, clips, earrings, bracelets, decorative inlays (e.g. used in belts). Keep in mind, that the process of jewelry making from antiquity until modernity was based on the traditions and technology introduced by the Egyptians. The objects that you see here on display were discovered inside the tombs of various wealthy merchants from Kalavasos, Kouklia and even at the Hala Sultan-Tekke Mosque, which turned out to be home to a Bronze Age settlement. All of these objects are of different origins (some were made locally and some were imported) and continue to inspire and amaze.

The «Geometry» age had reintroduced the use of animal imagery, including those from mythology; fruits (the famous Cypriot pomegranates); white metal bowls (antiquity-classics; most likely made of silver although there is no accompanying information).

The Hellenic period is represented through the gold-leaf belt ornamentation — and imitation of olive leafs used in victory wreaths. There are also pendants, earrings, bracelets with carnelian, rock crystals, emeralds and green-stones.

The official museum chronology ends with the Roman period, but the display cases still contain some objects from the early Byzantine period.

The last items on display in the jewelry case are early Byzantine silver dishes depicting wedding scenes (possibly wedding gifts), as well we jewelry featuring amethyst encrustations, pearls and even crosses.

On the opposite side is a collection of different lamps and lanterns: from ceramic to bronze Greco-Roman and early Byzantine periods. Here you will also find examples of antique stained and luster glassware: cups and bowls (from the French word «lustre» meaning «shine», and the Latin word «lustro», which means «I shine»). Luster dyes were a mix of organic paints and essential oils. The luster was used to decorate glazed porcelain objects, pottery and glass by applying a thin coat of the substance and scorching it. There is even ceramic jewelry with beads that resemble murano (Venetian) glass.

There is a small, but lovely section dedicated to decorative objects made of bones, including mammoth bones. The objects include hairpins, hand glasses, combs, etc. Next to these are objects made of alabaster (a natural type of plaster made with semi-translucent rock): figures, bowls, heads (Mycenaean, Egyptian, Classical and Hellenic).

Children will have a great time exploring the educational game zone located in this hall. The following hall contains a retrospective of the evolution of the writing system in Cyprus. It starts with the earliest evidence of its existence: Cypriot-Minoan writing from Engomi (has not been transcribed yet; 14th century BC), then examples of Cypriot syllabic writing (8th-3rd century BC; was transcribed by G. Smith at the end of the 19th century) and finally examples of alphabetic writing.

The following is a hall with sculptures from Salamis (2nd century). Marble statues and ceramic groups. There is a sculpture of Apollo Citharoedus playing a cithara, a figure of Mileandra made of white marble and Isida — made of black marble. All of these come with photographs of the archeological digs made in 1974.

We finally enter the last hall in the Museum. It is dedicated to ritual and religious sculptures. Among the objects on display here are tombstones and carved sarcophaguses. Once again we see flat anthropomorphic figures made with red clay (early and middle Bronze) decorating these tombstones and only some of them were carved out of wood.

In the center of the hall is a horizontal display case containing funeral ceramics: figures with cloths placed on their mouths. These objects confirm the practice of cremation that was brought to Cyprus from Greece (the ashes were placed inside a bronze urn and buried).

The display cases on the surrounding walls contain ceramic compositions and scenes, which provide a form of relief from this hall’s otherwise morose subject matter. There are several groups pertaining to different aspects of social life (750-450 BC): fishermen and the sea, everyday life, wars, music and dance, theater, cults and myths and production technology. There is a separate explanation for each section.

Afterword. Round about

After we wrapped up our tour of the Museum we decided to walk around it and we should say that it was well worth it. There is a souvenir shop to the left of the entrance selling toys, t-shirts (10-17 euros), jewelry (30-50 euros), books, magnets and pins (2 euros), puzzles and pillows (10 euros), DVDs (15 euros) and various other things.

The Museum has a small, but cozy old-fashioned park with benches hiding in the shade of the trees, a fountain and a kiosk-cafe that sells bottled drinks and sandwiches. We kept walking until we came upon a small exhibition «hiding» under an awning behind the museum. These objects were brought here from various archaeological sites. We were particularly impressed with the tall figure of a charioteer riding a quadriga.

There has been a lot of talk about moving this collection to a place that is more suitable for such valuable objects. This could mean that the Museum is approaching big changes…!

Address: Mouseiou, 1, Nicosia

Working hours: Tuesday – Friday, 08:00 – 18:00; Saturday, 09:00 – 17:00, Sunday and holidays: 10:00 – 13:00

First Wednesday of the month open until 20:00

Entrance fee: 4.5 euros

Telephone: +357 22865854

Additional information: www.mcw.gov.cy

See you soon!