While in the old centre of the seaside resort, you can sometimes come across some very unusual places, as well as meet some interesting and rather fascinating people.

Today we find ourselves in Larnaca, at the only Medical Museum in Cyprus, having received an invite from Mr Marios Kiryazis, the Museum’s founder, owner and curator.

Even if from childhood you’re a person who has been openly afraid of people in white coats, and the very idea of visiting a medical institution has never filled you with great enthusiasm, then allow yourself the opportunity to diversify your holiday experience on the island. You can do so by visiting this unusual, Neoclassical-style house, whose owner has managed to amass a rich collection of medical tools, folios of scientific publications and other objects considered rarities in our day, connected with the history of healthcare development in Cyprus.

-

Opened in October 2011, in the presence of Stavros Malas, the Minister of Health in Cyprus, the Museum is the first and currently only one of its type.

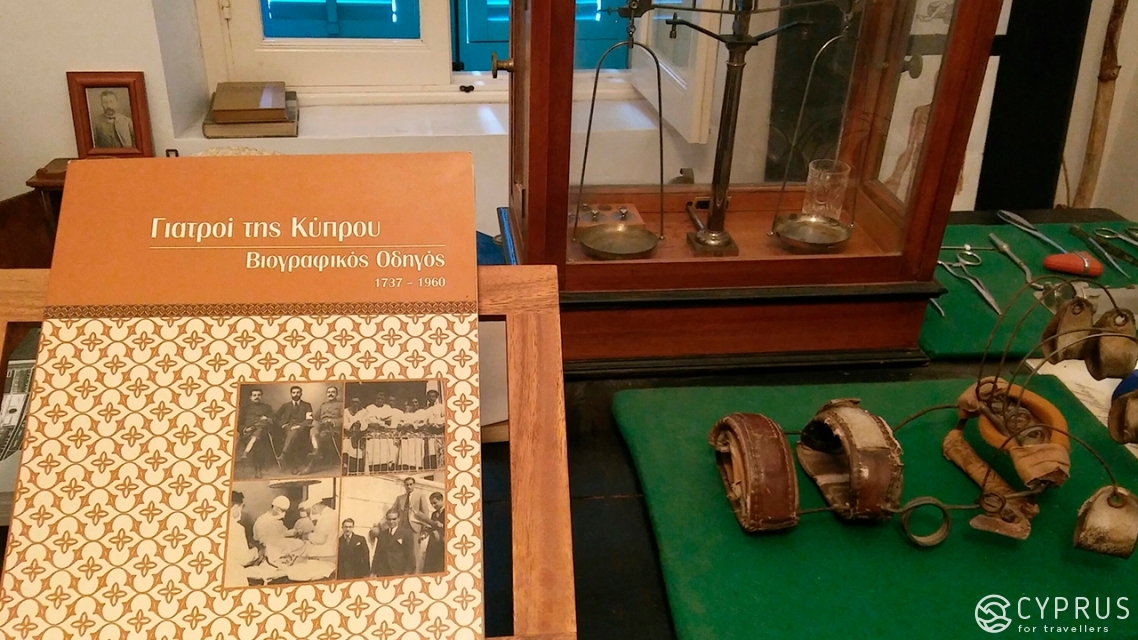

Marios Kiryazis, who, as we have already noted, is the Museum’s founder, is a fourth-generation descendant from a line of doctors and pharmacists native to Larnaca. The Museum is housed in a traditional, renovated urban mansion. Mr Kyriazis has donated rare exhibits to the museum foundation, many of which he not only inherited from his grandfather, Neoklis Kyriazis (1878-1956), but his great-grandfather, Antonios Tsepsis (1843-1905) — both of whom had a long history of practising medicine in Larnaca.

Interestingly, M. Kyriazis began his collection in 1990, but due to the absence of suitable space, many of the exhibits, which became museum pieces, remained in storage. They were only displayed from time to time, in the confines of temporary exhibitions on the topic of medicine and history.

This exhibition, directly linked to the practice of medicine and its history in Cyprus, represents a long journey, beginning in the Antiquity and spanning into the late 20th century.

-

The house is well known for previously having been a private residence, while curiously, the street on which it is situated, had a reputation for being “a street of medics” — an extraordinarily large number of doctors, nurses and pharmacists lived here, neighbouring each other. Nowadays, half of the locals are, one way or another, linked to medicine. As such, this place wasn’t chosen by accident but is thought to have been a well-made decision.

The museum founder believes his mission is to preserve and popularise information about the medicine of the past and other interdisciplinary knowledge in Cyprus. The main tasks consist of developing a dialogue between professionals and the public about modern medical practices, based on valuable experience and traditions.

The Museum is visited not only by tourists and groups of school students — or, in other words, the “potential patients” of medics — but also the owner’s medical colleagues, both from Cyprus and different countries: Russia, Belgium, Palestine, Romania, the USA and others. The Museum’s guests are members of various organisations, societies and unions, such as the Rotary Club [1].

After having met us, the owner of the collection, while showing us the Museum’s halls, disclosed a lot of interesting facts:

“This is a private museum of medicine and in that light — when medical traditions, including forms of therapy which are native to the island, are on display — it is unique for Cyprus! There are, in fact, medical terms in the Greek language, which are from our Cypriot dialect!

I began my collection, as they say, from various sources: some of the equipment and tools belonged to my family, for I’m from a dynasty of doctors, just like my father and grandfather. In keeping with this, I’m also a doctor of medicine, a gerontologist.

The Museum has existed in its current appearance, as you see it today, for five years.

Do you have any idea about which period the exhibition envelops? I wanted to show the development of medicine across “all” of its historical eras and periods — beginning with ancient healing, the methods of which were practised two thousand years ago, and further on: through the Antiquity, the Ancient East, the Medieval era and the Renaissance, right until the past, recognised by many as the late 1970s.

Visitors who wish to have a look around the exhibition also have the unique opportunity to do this freely: we open up the display cases so they can take a particular object in their hands and better familiarise themselves with it.

As you can see, everything works based on an idea!

By the way, our exhibition hasn’t been constructed in strict chronological order, nor any other form: every hall is “mixed”, allowing visitors to see and comprehend more, — in context, that is…

Are you interested in the history of this house? When I found it, this was all ruins, with only the facade having survived… we rebuilt everything, restored the historic building anew. Now, the Museum occupies the lower floor.

You ask, how do my colleagues react to this “Museum” passion? They are well aware of this collection, and when something appears before them, which is no longer used in the practice of medicine, then all of it is brought here. Therefore, many exhibits, including rare photographs, have appeared thanks to donations and gifts received from Larnaca’s medics.

Yes, I suppose our collection has now reached its limit (Marios laughs). Nowadays, there’s no longer any free space…”

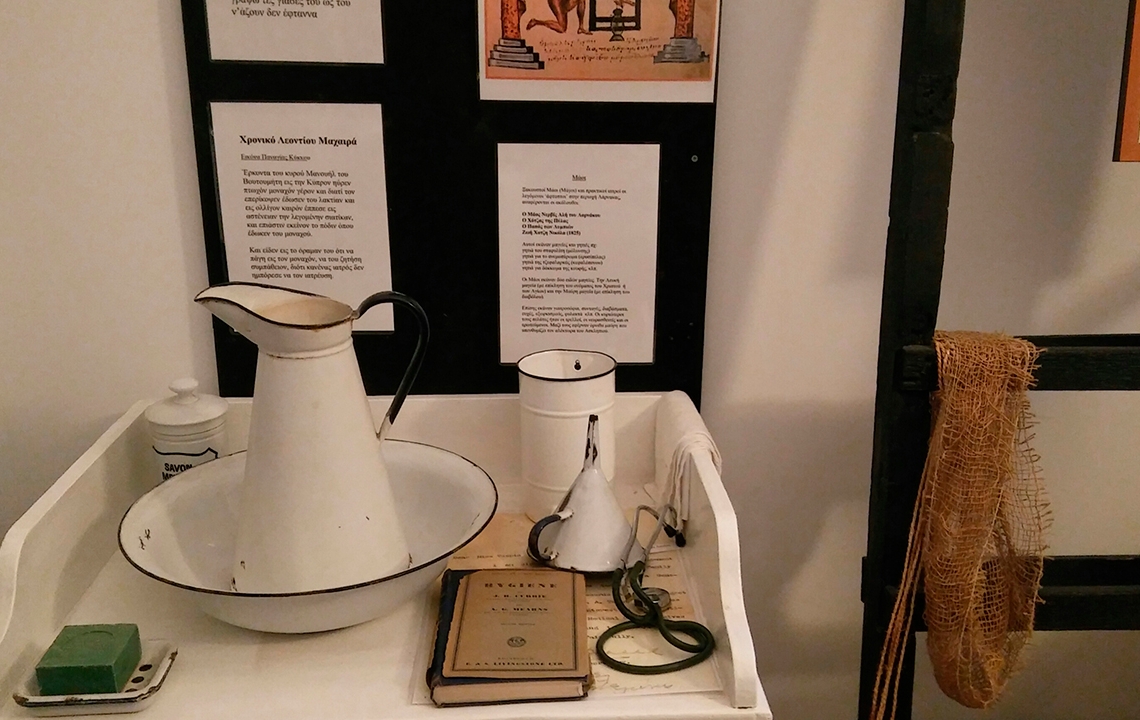

There are posters and documents displayed on the walls of all the exhibition halls, which include old Cypriot poems, as well as verses on the topic of healing and physicians, with descriptions of medical courses. Aside from photos taken from the pages of old folios, reproductions of famous paintings, engravings and other things, you can see various certificates belonging to the practising doctors of numerous periods. The current owner’s certificate is also on display. You will also come across a series of practically forgotten statements regarding medicine under the rule of the Byzantines, the Franks, the Venetians and Ottomans.

An Excursion through the Halls

Halls

There are many framed works on the walls of the urban house’s main hall (if we recall, in Greek homes, these rooms were known as “ilyiakos” or “sun rooms”). They feature posters and reproductions of both famous and little-known works of fine art, portraying the history of medicine from ancient times (the Antiquity and the Arab East), through the Medieval era and into the early 1800s. The images depict scenes from operations performed without anaesthetics, as well as treatments of epidemics and medical practices in monasteries.

Hall 1 (The exhibition begins in the rooms on the left)

This is the first room on the left of the main entrance. The pharmacist’s cabinets contain original bottles of varying sizes, with different “components” and traditional mixtures, as well as medicines ready for use, which have long been manufactured by Cypriot pharmacists. Alongside these items, we can also notice prescriptions, syringes and ampules with injections from different periods, — they testify to the development in both society’s knowledge of medicine and the technology which was used. Though there are many unique items on display, the “bullet extractor” will most certainly grab your attention.

After popping the door open a little, the Museum’s hospitable owner asked us to peer into a pair of rather eye-catching bottles.

“Look, here we have the first coca-cola on the island: the liquid, as proven by the labels on them, has been poured separately into these two small brown bottles. Pharmacists would usually have used them for mixing prescription medicines… today you can merely catch a light scent and notice some brown sediment at the bottle’s base. Do you know how it was used for medicinal purposes? As a tonic mixture: in cases of anaemia, malnutrition and body fatigue…”

The most awe-inspiring exhibit (first invoking somewhat mixed feelings, due to its terrifying appearance) is a training apparatus which was used to strengthen and develop arm muscles, administered in physiotherapy during the late 19th century. It’s composed of a spring-loaded device, where each finger movement is fixed and works on the principle of a counteracting force from the separate springs. While stretching the springs, the patient would have the opportunity to restore function to their hand.

Amongst the other exhibits, there are some meant only “for an adult audience” — for instance, a phallic-shaped object, which researchers assume would have been used to treat what was known as female hysteria.

Alternatively, another find, considered a rarity today: oil extracted from Larnaca Salt Lake, which was used to treat skin damage and wounds or bites caused by insects.

Mr Kyriazis explains: “Amongst the medicines, drugs and remedies traditionally used in the past, you can see some “salt oil” obtained from the Salt Lake in Larnaca. As you’re aware, a salt crust appears on the lake’s surface when it gets hot. After exposing the crust, you were able to extract the salt oil from a small depth (known as “elamiro”), — it worked superbly as a compress to aid in healing wounds or damaged skin, and was also used by the island’s doctors in cases of degenerative spine diseases”.

A multitude of old, medical-themed poems and proverbs are also on display in the hall.

Hall 2

As for the various exhibits in the second room, there is an X-ray machine with a couple of images, an electronic EKG machine and an operating table.

A pharmacist’s cabinet also stands in here, where, amongst other things, you can encounter several medical items dating back to the 1850s. These include tools used during abortions, leeches, a tonsil-extracting instrument and what’s more — an electromagnetic apparatus from the Victorian era, as well as various other rarities.

Next to an impressive machine used for inhalation, there was a rather peculiar looking bottle… As Mr Marios says, after approaching us: If you want, you can open it and inhale breathe what’s inside. Only, there’s a high likelihood you’ll immediately fall asleep. After suddenly getting cold feet, we declined the offer to experiment. The substance was evidently chloroform.

Hall 3

This hall mainly serves as a research and study centre, providing students and scientific workers with a medical library full of books in Greek, French, English and the Cypriot dialect.

Doctor Marios sheds a little light for us: “This room was both the doctor’s cabinet and work library. In the large, old cupboard, you can find various rare publications released primarily in Germany and England. A superb library, the tomes of which, as you can see, are composed of works from different specialities and spheres of medicine. There are also atlases of medicinal plants, reference guides and other titles. The rare archived documents (prescriptions, certificates) and photo materials once belonged to my grand dad”.

…True, this cabinet, which formerly belonged to a household name in medicine, had an air of peace and calm drifting through it. That was, right until the moment we cast our eyes on a mannequin standing in the corner. It was tangled in chains and wearing a straitjacket — an eerie sight indeed… evidently, doctors weren’t always stuck in a rut, and their days weren’t forever quiet…

Hall 4

… So if, for some reason, while in the previous rooms, you may have felt a little tense from seeing some of the former doctors’ frequently used belongings, then this part of the exhibition will be different. Here you’ll feel tender emotions, or warm memories at the most…

The Main Theme: Childbirth and Procreation.

The exhibit of an old cot with a canopy over it is genuinely touching. Inside there are gifts given to newborns and books which would’ve assisted young mums.

Amongst the additional items in the exhibition, there were various aid tools and a midwife’s bag.

Featured in the very centre of this hall, you can see a gynaecological table (according to the info-stand, almost half of the patients, who underwent screening, were women native to Larnaca).

The hall features a copy of the famous Hippocratic ladder — one of the traction techniques: it involved stretching the patient through “shaking” (we have already seen a reproduction of “how this works” in the hall) on a wooden ladder, and was used to treat dislocation of the hip or neck.

The medical info-section, given to the Museum by the old Larnaca hospital, represents a collection of posters with medical caricatures and information on traditional Cypriot therapy.

-

Dr Kiryazis comments: “… In the display cases of the last hall — which, actually, our visitors most often stop by — there are numerous, phials, bottles and other items. You can still read the names on the old, even antique, labels, as well as, sometimes, the ingredients contained and the instructions for their use. The pharmacological substances, which used to be administered, are still used today. Let’s take aspirin — these tablets are close to 100 years old (while acetylsalicylic acid was discovered in the late 19th century) and were used in monasteries, as part of a kommandaria-based tincture, to treat coughs… in spite of the decades gone by, the blue bottles remain here still, almost filled with the tablets”.

The museum owner removed the lid of a dark-blue, glass bottle. At the same time, having seen the viscous, black liquid contained, we immediately sensed how the concentrated, recognisably spicy scent of ancient Cypriot wine, began to permeate the air.

-

However, our acquaintance with the Museum wasn’t only limited to halls and lobbies.

“In creating this Museum — Marios tell us — I decided to continue with the same concept even in the toilets. In addition to old posters hanging on the walls by the sinks, a chalkboard has been set up in each cubicle, which guests can use to write something. They can even use it to draw a picture of something “medical”, if let’s say, in their moment of “relaxation”, under the impact of what they’ve witnessed in the exhibition halls, a wave of inspiration descends over them”.

The director further invited us to continue onwards into the back yard, which exited into a physic garden (in which Marios grows mint, basil, lavender, sage, lemon balm and marjoram). Here there is a unique room — a conservatory with an area for hosting events [2], known as Art and Medicine.

The Medical Museum, it turns out, frequently holds these events, which include the use of equipment for video presentations: they consist of meetings, presentations and public discussions with professionals, as well as exhibitions. Even “medical” animation videos are shown.

Guests and participants to these culturally enlightening and educational events are served herbal, as well as other revitalising beverages.

Three main research projects are currently in process on the Museum premises:

- A plan to compile a Cypriot medical dictionary, aimed at collecting and publishing all historical terms of medical significance which have been spread throughout Cyprus in various ages. The finished publication will envelop all specialities, including anatomy, pharmacology and nursing.

- The study of “unusual” traditional healing practices. This project involves the collection and classification of information on all methods and resources which were used in the past, to cure or alleviate the progress of a disease — however strange they may seem to us today. What would you say, for instance, to the use of cure-alls such as baked lizards, or powder which “combats” balding; or how about the use of donkey faeces to heal infections and other things similar?

- A project which involves the collection, exhibition and subsequent publication of Medieval, Byzantine and early Cypriot literature. It will also research medical-themed folklore, which consists of verses, ballads, desires, folk tales and even satirical songs.

It’s probably worth delving into a little more detail about the founder:

Marios Kyriazis is a medical doctor, gerontologist and writer.

In 1996, according to the reference guides, Dr Kyriazis founded the Historical Medical Equipment Society, which aims to study old medical tools linked to the history of medicine in Britain.

In 2001, in collaboration with the municipality of Larnaca, he organised an extensive exhibition on the history of medicine in Cyprus (Medicine in Ancient Kition and Old Larnaca), which was accompanied by a book presentation.

In 2008, following in the footsteps of other family philanthropists (such as his grandfather and great grandfather, Neoklis and Damianos Kyriazis), he both founded his Medical Museum and a cultural charity foundation, which strives to preserve old and antique Cypriot medical items and traditions, as well as to enlighten the public with respect to the history of medicine on the island.

Did you know: several facts from the history of Cypriot medicine until the island gained independence

The medical practice of Ancient Cyprus is considered to reflect the general techniques administered by physicians in Ancient Greece and the countries of the Middle East. Local doctors usually used incense, myrrh, olive oil, tree resin, wormwood, bitter herbs infused with water and of course, mandrake. Skull trepanation — a “procedure” considered to relieve a patient from possession by “evil spirits”, effectively aiding against epilepsy — began to be administered from as early as 2 B.C.

Interestingly, there was a popular concept of body cleansing and water disinfection amongst all the local healers, who often encountered diseases common throughout all Mediterranean countries (such as food poisoning, sunstroke, infections, furuncles, tuberculosis and poliomyelitis). From time to time, populations were overwhelmed by epidemics, and many saw devout faith in God as the only salvation and cure to their ailments. Healers, on the other hand, knew how to manufacture talismans, as well as perform special rituals and incantations; in addition to the purely medical methods and instruments, which they had at their disposal (based on honey, zinc, propolis, myrrh, wine and sea salt). The sick were tended to in local sanctuaries, under the observation of pagan priests.

In 3 B.C., there was a famous Cypriot physician named Diagoras, who was referenced by Dioscorides, as well as Pliny and others, with regards to his in-depth knowledge of pharmacology. The “Collirio” technique, which was used for burns, treatment of migraines and eye infections, was attributed to his authorship. In the Museum of Cyprus in Nicosia, there is a ring with the inscription “Diagorou” and an image of Medusa’s head.

There were other great physicians and doctors from Cyprus, whose names have also been preserved by history. However, the most renowned physician was Apollonius Kition (1 B.C.), from pre-Christian ages — he authored a significant number of medical treatises, several of which were based on and spawned from the experience of Hippocrates.

The influence of Byzantium on Cyprus (647-1911) is evident in the development of the island’s local medicine: the doctors of that time were the first to provide equipment to hospitals and almshouses, where the suffering where tended to, regardless of their social or economic circumstances (known as “nosokomeia”, “xexones”). At that time, women in childbirth were helped through labour by “mammouthes” (midwives).

With the arrival of the Lusignans (1192-1473), doctors were allowed to practise medicine only after receiving permission from the bishop and on the recommendation of more experienced colleagues. Amongst others, the following techniques were mainly practised: fumigation, cauterisation, body cleansing and of course, pilgrimages to sacred sites. There was an Italian, known as Mastre Gky (late XIV century), who lived in Cyprus and was once a personal friend of Petrarch. Under King Pierre I, doctors actively participated in political life on the island. Mastre Pier Vryonas, Mastre Gabriel Zintilis, and Mastre Synglitikos, were among some of the other specialists from that period, all of whom were Greeks.

Under Venetian reign (1489-1570), the government paid some doctors, while others, at the same time, remained private. Phlebotomies, cauterisation, cleansing and inhalations were commonly administered. The two most well-known doctors, who were referenced in sources, were Bulien de Nores, who came from a family of aristocrats, and Jane de Rames, who was most likely a native Cypriot.

Whenever Cypriot rule transferred to the Ottoman Empire (1571-1878), the sick were great in number on the island: frequent epidemics, coupled with a lack of doctors and insufficient medical aid, hammered the island’s population for a long time, from the late XVI to the early XIX century. The first famous doctor from this period was Aloise Cucci — a man of Italian descent, who had a reputation of being a very experienced and wise doctor on the island. History has also left us the names of many other doctors, both Cypriot and French in origin. For more details, see here.

From 1830, a so-called urgent need was brewing for the government to organise healthcare on the island. Soon after, in 1835, the first quarantine in Larnaca (the city port was often becoming a breeding ground for diseases and epidemics, — after all, dangerous bacilli were making their way to the island together with goods from other countries) received financial support from both the Greek and Turkish communities.

Nevertheless, the island, which was under Ottoman rule, hadn’t had a unified, state medical system for a long time. Reports of a Turkish military hospital have survived, which operated nearby the Paphos gates in Nicosia. The House of Nuns was another famous hospital establishment registered in that period. Founded in 1844, it provided free healthcare to the people until its closure in 1992.

In the first decades of British rule (1878-1960), medics in Cyprus were also given the opportunity to receive education in Britain. In 1879, the first official hospital was created in Larnaca, the primary doctor of which, was Dr Heidenstam. All of his inpatients were housed in not just one, but several building blocks in the city centre.

Museum Address: 35 Karaoli and Demetriou Street, Larnaca

Opening Hours: Every Wednesday and Saturday, from 9:00 to 12:30. For visits at a different time, please agree in advance by calling: +357 97606424

Free entrance.

Stay with us and until next time!

[1] Rotary International — an international organisation with the declared aim of uniting business and professional leaders, striving to provide humanitarian services, as well as to encourage “high ethical standards in all spheres of activity and the strengthening of goodwill and peace all over the world”.

[2] Amongst the most exciting events which have taken place in the Museum, it’s worth noting: “2000 years since the death of Apollonius Kition” (May 2013) and practical demonstrations within the framework of World Tourism Day (September 2018), including an exhibition of medical caricatures, “Medical Saints of Cyprus”, under the auspices of the bishop of Kition and performances by Kalogera primary school pupils. On 22nd May 2014, an “Evening of Cypriot Medicine” was held, together with the Association of Doctors of Larnaca and the city municipality.