Cyprus Theater Museum opened on March 26th 2012 thanks to the private collection of Nikos S. Nikolaides — a famous Cypriot and a big theater connoisseur. The permanent exhibition, which includes rare and unique objects (costumes, billboards, decoration sets, sketches, video and other archival material), describes the significant stages in the development of theater on the island.

This colorful, multi-faceted exhibition will be of interest to adults and children. The museum invites its visitors to test their acting skills by performing on an improvised «stage».

In 1987 Nikos S. Nikolaides (1909 – 1989), an optician by profession and a talented amateur actor, donated his rare theatre archive to the Municipality of Limassol. By doing so, he laid the foundation for the establishment of the Cyprus Theatre Museum, which helped to immortalize the history of theater on the island.

Throughout his life Nikos S. Nikolaides systematically collected material relating to theatre and its activities in Cyprus.

In 1989 the search for a suitable site which would house the Cyprus Theatre Museum began. After Panos Solomonides’ generous donation to the Municipality of Limassol, the Kouvas printing factory was purchased, which was gradually transformed into the Panos Solomonides Cultural Centre that opened its doors in 2010. Starting in 2012 the venue became the site of the Cyprus Theatre Museum, which, apart from the collection of Nikos S. Nikolaides, also includes Giorgos Filis’ archive with material of the Organisation for the Development of Theatre (OTHAK), Giorgos Vatyliotis’ photographic archive, material belonging to the Cyprus Theatre Organisation, as well as exhibits from many theatre professionals and companies that donated or lent various objects from their unique collections.

The Cyprus Theatre Museum presents the history of theatre activity by various groups in Cyprus from antiquity (the Hellenistic and Roman periods, 4th – 3rd century BC) to modernity. Through this historical journey, the different aspects of the splendid world of theatre and the people who work for it unfolds before the eyes of the visitor.

Visitors of any age can expect to be immersed in a magical journey through the different stages of theater development in Cyprus, with particular attention paid to the defining periods in its history.

The history of contemporary theater in Cyprus

It is thought that the emergence of theater in Cyprus happened thanks to the arrival of the British after 1878.

The first theater production dates back to 1880. It took place in a military camp in Troodos — an incident mentioned in the book titled «A Historical Recollection of a Bygone Age through engravings» by G. Lazaridis. It was an outdoor play, which incidentally cast a man for its female part.

Starting in the 1920s the famous Pancyprian Academy began to define educational goals and principles in Cyprus and started leaning towards the value of Hellenism. This resulted in a favorable working environment for Greek immigrants, among which were many Greek theater groups. To a large extent these groups were responsible for reviving and developing Cyprus’ theater culture in the period between 1878 – 1940. Each year they organized theater tours from Greece that lasted several months and brought Greek plays and shows to Cyprus. They brought the same plays that they staged in Athens, Constantinople, Smyrna and Alexandria to the different towns and villages in Cyprus. The only difference was that Cypriots were particularly keen on patriotic plays, which were heavily censored in the Ottoman-controlled part of the island.

It is quite interesting that the most popular theater plays were brought to Cyprus 2 years before the emergence of booksellers. Romantic comedies were staged here at approximately the same time as in Greece. For example, «Marule’s Fortune» was staged in Greece in 1891 and in 1893 — in Cyprus. However, the most important factor in the development of local theater culture was the presence of Greek theater companies in Cyprus. It is no wonder that local amateur theaters were modeled after their Greek equivalents.

From the beginning of the 20th century and up until the 1940s Greek theater companies of various professional levels began to move to Cyprus. Among the well-known theater groups of those years were «Pancyprian» with young Aimilios Veakis, Xenofon Isaiah and the Gonidis family (season of 1906 – 1907); the theater groups of Rosalia Nika, Edmond First and Julius Liminiotis (1912 – 1913); the theater collective of Aimilios Veakis and Christoforos Nezer (1923); «Kotopouli Rex» (1927) featuring Aimilios Veakis, Pericles Gavrielidis, Vailis Logofetidis and Aleksis Menotis; «Argyropoulou» Theater (1930), «Apostilidis & Femistocles Nezer & Kimis Raptopulous» theater group (1935); and finally the Aliki — Mousouris Theater Company (1938).

These theater collectives, together with many other groups, had a rather extensive repertoire that included romantic comedies, classical Greek comedies, tragedies and drama (Oedipus Rex was especially popular), as well as foreign plays by great playwrights like Shakespeare and Molière, patriotic plays (such as the endless «Panathenaea» operetta, which ran from the 1920s to the 1940s) and lastly plays by the more modern Greek and foreign writers (Xenopulous, Kaskaris, Sinodinos and Spiros Melas, Isen, Oscar Wilde, Bernstein and Tolstoy).

Now let’s talk about local theater that started out on an amateur level and gradually reached professional heights.

Amateur theater groups and collectives, whose primary focus were antique plays, were all part of various organizations and clubs, including politically and socially-oriented ones. These organizations used theater to promote their ideals and values. Beginning in the 20th century the island was gripped by a religious dispute that divided people into two camps: «Love for the people» and «The Cyprus Association». Members of the latter camp shared a hostile view of the British colonizers, while members of the former camp had a more conciliatory approach. Both of these camps continued to stage plays, releasing new theatrical productions every month.

At that time Cyprus was still under the control of Britain while at the same time ideologically tending towards Hellenism. All this made a significant impact on theater arts on the island.

Interestingly enough, the first play that was staged in Cyprus was also written by a Cypriot named Petros Praksis. We should also mention the Makridis Brothers. They wrote several screenplays in 1918, which were staged in all major cities (first in Paphos and then in Limassol and Larnaka, where they were picked up by local theater collectives).

The period after 1920 saw new changes brought on by the October Revolution in Russia. As a result of this new worker unions, that included theater employees, sprang up in Limassol and Nicosia,

During World War years a professional theater was founded in Nicosia (1942) thanks largely to the efforts of a Cyprus poet Costas Montis.

Costas Montis (1914 – 2004) was a famous Cyprus poet, Roman scholar and playwright. He was born in Famagusta and played an important role in shaping a new generation of playwrights and writers. He came to Nicosia in 1942 and together with Achileas Lamburidis and Fivos Mussulidis he founded the first professional theater in Cyprus called «Lyrico». However, the theater had to be shut down in 1944 and Montis returned to Morphou where he worked at the «Free Voice» newspaper (Ελεύθερη Φωνή ) up until 1947. In 1948 he was made editor of «Ethnos» newspaper and then in 1953 he started publishing his own Cyprus Trade Journal, which came out in Greek and English. During the independence struggle Montis joined EOKA — a Cypriot nationalist guerrilla organization in Nicosia. In 1961 after Cyprus gained its independence, the writer was assigned as head of tourism — a position he held until 1976.

His most famous screenplay is called «Entry into stress is prohibited» (Απαγορεύεται η είσοδος στο άγχος) and was written in 1973.

Montis was a widely recognized writer and became a recipient of many different awards. His books were translated into several languages. He was awarded honorary doctorate degrees by the University of Cyprus and the University of Athens. He has also been nominated for a Nobel Prize and in 2000 thanks to his intellectual accomplishments he was made a corresponding member at the Athens Academy of Sciences.

«During the 70 years of his literary work, Montis was able to masterfully and truthfully describe the passion and the different emotional and historic fluctuations of the soul of Cyprus and its people… He used the entire linguistic, historic and cultural spectrum of Hellenistic traditions, which he incorporated into his art with incredible poetic force highlighting the character and the values of the Greek people» (an excerpt from a speech by Nicholas Konomis). For more information read this.

From 1945 to 1955 there was a new massive wave of Greek actors coming to the island. This was a time when Greece faced serious social and economic problems (as a result of German occupation, civil war and starvation). Those, who worked in theater, were forced to look for jobs among Greek diasporas outside of their country.

A range of different theater groups visited Cyprus during that period: «Manolidou &Aroni & Horn» and «Vembo» in 1945; «Kakopuli» theater collective in 1946 «Katerina» theater company and «National Theater» in 1947; «Anna and Maria Kaluta» in 1949; «Marika Cotopulti Company» in 1951; «Mimis Fotopulos», «Lambeti & Papas & Horn» and «Dimitris Mura» in 1954. This influx of Greek theater companies and actors obviously limited the work of local theater groups, which were looking to expand and develop.

Because during that period there wasn’t a single law regulating the development of the arts and culture, everything that happened in that sector was a result of uncontrolled actions by the above-mentioned Greek and Cypriot artists as well as local creative organizations and collectives, which were able to keep the Cyprus theater life afloat. Immediately after the war the Communist Party of Cyprus established the first theater school called «Prometheus». The school brought together many of the theater workers from Greece as well as Adamantios and Mary Lemos.

We shouldn’t forget that Cyprus is conveniently located at an intersection of important sea routes. This includes the «big theater» route, which began in Constantinopole or Smyrna and ran in the direction of Cyprus, ending in Egypt or the Greek communities in Palestine. However, the situation changed following Cyprus’ independence in 1960.

1961 saw the establishment of the Theater Organization (OTHAC), which was financed by the government of Cyprus and Greece. OTHAS sought to follow the existing rules of theater practice and it worked in the beginning, but then the organization changed the repertoire and left only farcical shows.

Greek ideals and theater school existed alongside Turkish theater traditions and shows. In the 1920s all large cities on the island had Cypriot-Turkish theater groups giving shows from time to time.

Many of the plays shown during the period between the 1920s – 1960s were written by Namık Kemal (1840 – 1888) and included «Fatherland», «Torch», «Shepherd», «Victims of Lies» and «Miracle». Also popular were works by Turkish writers like Avukat Fadil Niyazi Korkut, Hikmet Afif Mapolar, Nâzım Ali İleri, İsmail Hikmet Ertaylan, Osman Talat and others. Over the course of 50 years theatrical productions by Turkish Cypriots were shown in local movie theaters. One of the main accomplishments of the Turkish theater community is considered a radio production of «Alikko» and «Caher». Interestingly enough, the characters in these Turkish plays spoke an old dialect common among villagers — a symbolic and meaningful choice for the Turkish-speaking audience.

There were female actors as well. Some of them later became famous, such as Mineh Sinui — a star on the popular TV show called «Bizimkiler», which was broadcast on Turkish television; Aikhatun Atechin, who gained fame thanks to her part in a one-man production of «Shirley Valentine» (1993) by Willy Russel (1947).

Today there are several foreign actor collectives and theater groups working on the island. For example, ACT — is the oldest British amateur theater group in Cyprus, which is based in Nisosia. The group was founded in 1982 and in the following years produced numerous plays from farce to tragedy. These actors’ main goal is to promote English-language drama in Cyprus. The president of this theater group is Jane Bywaters.

At the Museum

When you open the metal door and enter this modern, industrial-style building, you are immediately immersed in the backstage environment of theater life. The borderlights illuminate the objects on display in these half-lit halls that house the permanent collection. It is hard to resist the glamor and mystery behind the objects hidden inside the window cases. However inaccessible, they are saturated in the emotions of the actors who wore and used them and thus make a strong impression on the viewer.

As we already know, the basic characteristics of Modern Greek and Cypriot Theater are their love for their antique heritage. We should also say that ancient Greek theater is not only the foundation of theater in these countries, but also in the entire world (the history of antique theater spans across 1000 years from 6th century BC through 4th century AD). This period saw the birth of new disciplines and principles of playwriting, acting and stage decorating, which laid the foundation for what would later become European theater art. Theater played an important role in the lives of ancient Greeks. It served as a platform for the dissemination of new ideas and as a discussion forum. Because of that, dramatic poetry (tragedies and comedies were composed in the form of poetry) pretty much forced out all other genres.

The concept behind the exhibition implies that the visitor slowly walks down the halls, gradually entering a parallel reality of art, games and legends. The first part of the exhibition is dedicated to history (330 – 300 BC) and explores antique Greek Theater with its drawings and architectural plans of ancient amphitheaters (including Kourion). It also describes the different plays that were staged during that time and up until the present day (1980s – 2000s). Nearby is information about the work of the Theater Organization of Cyprus [the purpose of THOC is to promote and cultivate theater arts and culture in Cyprus and to facilitate collaboration between Cypriot and foreign actors. This semi-governmental organization is run by nine board members who are appointed every 30 months — ed.]

Today’s collection consists of photographs, print material (newspapers, posters, playbills and billboards), decorations, sketches, costumes, audio-visual materials and many other objects to help the visitor walk down the path of history and end up behind the scenes of theater life.

The exhibition features all forms of art used in theater: literature, music, choreography and singing, fine arts (decoration) and many others. And of course the main «medium» of dramatic arts is the actor.

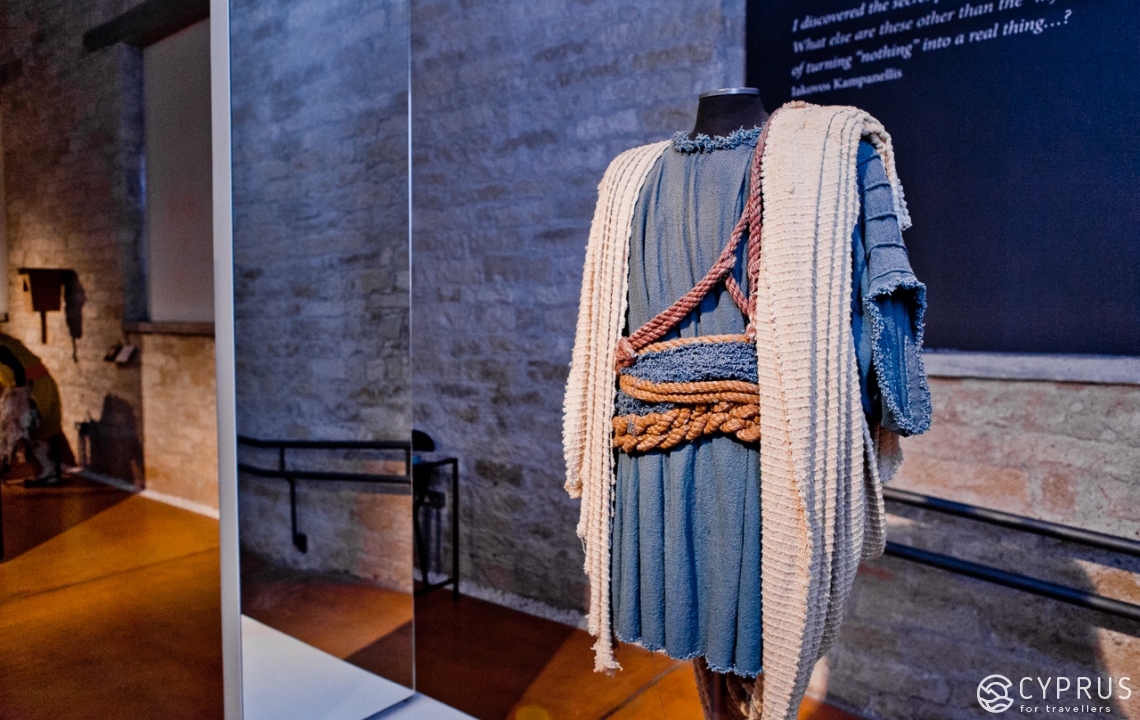

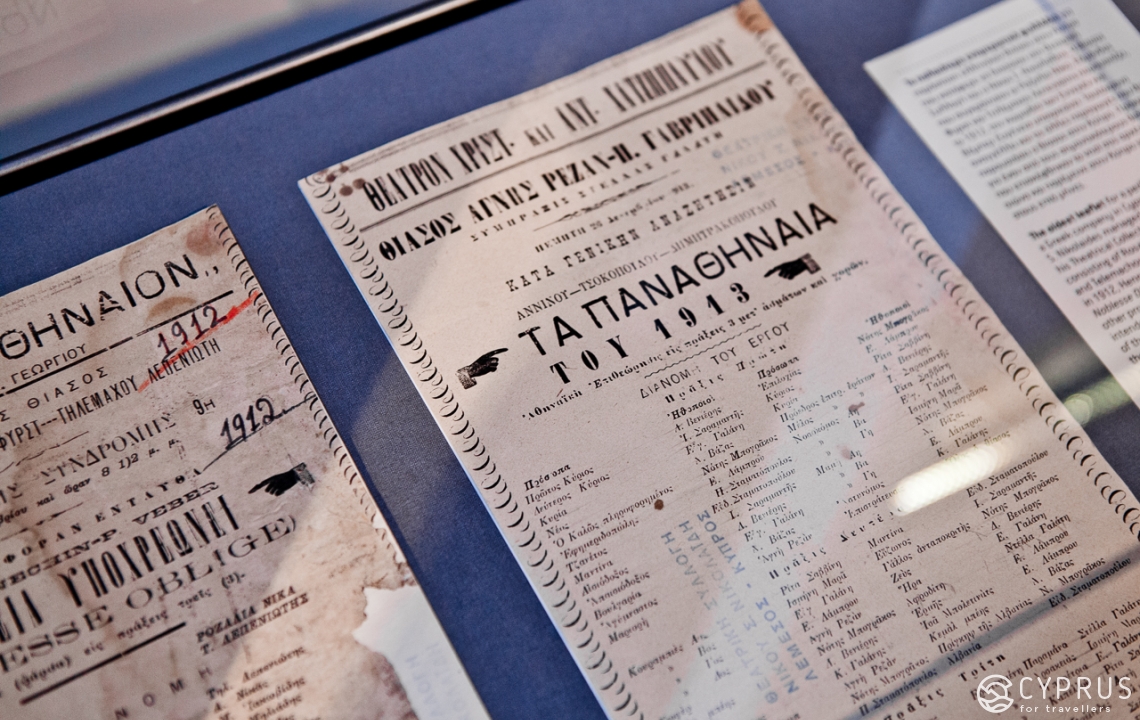

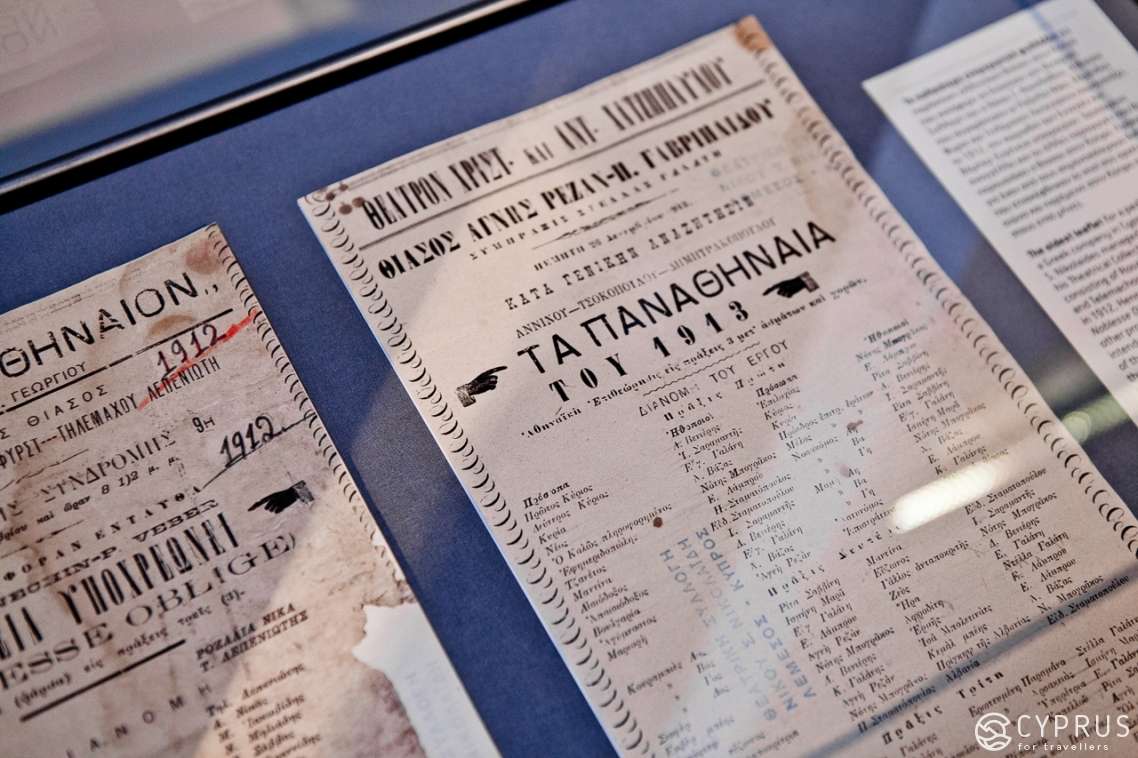

The window cases: the ones you see as you first come in contain, among other things, the earliest surviving playbills (1912, «Athineon» Theater). You will also come across sketches by Telemachos Kanthos (1940s), some of the costumes from the production of Ajaz (THOC, 1973) and a stage set for «To Neron tou Dropi» (THOC, 1974) — all particularly old objects in this collection.

One of the most recognized symbols of the Museum in Cyprus is the silhouette of a famous theater connoisseur and amateur actor Nikos S. Nikolaides. You will see an old blown-up photo of him as a character from a 1940s play and immediately before this photo is a mannequin standing in the same position and wearing the same stage costume.

The oldest poster in the collection of the Museum dates back to 1879. It is the only poster that belongs to Greek Theater.

The following section is dedicated to the stage and contains photographs, sketches, finished costumes and props.

One of the steps in preparing for a play is drawing sketches for stage decorations and costumes. The stage designer then creates decoration models and works on costumes — the future aesthetic look of the play.

Did you know that the theater stage as we know it has not changed its appearance since the 17th century.

Many of the window cases contain models of these «boxes». Images on the photographs trace the way the artist’s idea gradually took shape on a real stage. Nearby is archival material about play rehearsals, its cast, drawings of costumes and costumes themselves.

If you look at some of the 1950s posters, you’ll notice that the photographs of the male actors come with their full names, while female actresses only had their first name printed on the poster (e.g. «Evy», or «Olga»). We still don’t know if those names were real or not. You might wonder why this is the case. The thing is that Cyprus used to have a pretty conservative society, and women weren’t even allowed to appear unaccompanied in public, let alone have their names revealed in theaters.

However, not only actresses had their names hidden, but costume designers and seamstresses who created exquisite works of art often went unknown to the public since their names too weren’t mentioned anywhere. One of the museum employees told us that at some point some of the costume designers came to the museum to donate their work. Pretty soon museum signs will include the missing information about the costume designers and the seamstresses.

Since we are on the subject of costumes, most of those featured in the museum collection, were created for antique plays as well as plays by European playwrights like Molière (Jean-Baptiste Poquelin 1622 – 1673), Carlo Gozzi, Friedrich von Schiller and others.

We keep moving through the exhibition and come across the model of «Trojans» — a tragedy by Euripides (480s – 406 BC). The director of the play, Haris Kafkaridis, and the stage designer chose a more modern narrative for this classical play. The miniature version of the play shows an unusual creative decision: in the back of the stage and on its sides we see photographs of Greek Cypriots, who went missing in 1974 as a result of the Turkish invasion. The director draws a connection between the Cypriot tragedy and the Trojan tragedy. We also see the costume of Helen of Troy, the daughter of Leda (Nemesida) and Zeus (dated 1992).

Where did these costumes come from and what fabric were they made with? It depends on their origins. Some of them are part of the THOC collection. They were created and used in plays shown at the National Theater. They were made using expensive fabrics: handmade lace, pearls, foreign silk, etc. The organization obviously has its own studios, seamstresses and designers, but we can only learn their names and who they were when they personally bring something to the Museum or when someone who knows them do. We were told that the Museum had a recent visitor — a woman, who turned out to be the only dressmaker working with the original sewing technique: free weaving using lace and cords, which creates an «antique» effect. Two of her works are part of the museum collection: a voluminous black costume with a feathered mask and a white, vapory costume (both of which were created for Greek tragedies).

This wonderful costume designer’s name is Clara Zahariki Georgiou.

We slowly move to the comedy section. The first characters we come across are from the works by Aristophanes (444 – 380) and include the famous frogs from the «Frogs» play, the hyperbolized female figure and slices of a gigantic watermelon — all stage props from a comedy called «The Women Celebrating the Thesmophoria».

Suddenly, we discover an echo of Cypriot history and culture in one of the papier-mâché masks, which is essentially a massive costume (whose upper part is supported with a special device) or an imitation of antique Cypriot pottery. A museum employee told us that this figure appears on a 2-euro coin in Cyprus, whose prototype could be the Idol of Pomos. The figure also displays heavy use of macramé — a popular technique used in theater costumes for historic and antique-period plays.

There is yet another interesting thing to look at — the costume and the mask worn by character from the «Raven» — a comedy play by Carlo Gozzi (1720 – 1806). Next to the costume there is a display showing all of the stages of the actress’s magical transformation: from the moment she applies her make up, to the moment she puts on her costume (which resembles an island covered with bits of fabric) and to shots of her appearance on the stage.

It’s probably time to take a break and do something fun. We find ourselves across from a stand featuring theater and masquerade costumes and hats. You can pretend to be any actor or actress and try something on. School children are particular fans of this part of the exhibition. They spend a lot of time here: touching, playing and trying things on. If you came together with a child, he or she will likely be offered a chance to make a hat for his/her doll, or wear one of the available costumes, put on real theater make up and enter the spotlight of the stage.

The next section of the exhibition is dedicated to children’s theater and consists of colorful characters and costumes (e.g. mermaids, fairies, dragons, etc.). There is even a character from the Animal Farm play by George Orwell — a cow, which looks likes an eccentric lady wearing a hoop-skirt and a bunch of buckets (only children can figure out what is what here).

Now we are at the «core» of the collection: three costumes from «Mother Courage and Her Children» — a play by Bertolt Brech, which has been recognized as the epitome of the epic theater movement. The window case features three costumes belonging to the mother character in the play. The costumes appear to age in front of the viewer — a symbol of time and the challenges encountered by the characters in the play. The plot of the play centers around the Thirty Years War — a period of tragedy for Germany. This part of the exhibition includes other costumes from the most crucial plays in the history of Cyprus theater.

The following window case contains costumes from a musical production «Helena» (1977), which was staged in Athens at the Ethniko Kotopouli-Rex Theater. The costumes reflect the resourcefulness of the designers at the time. Because Cyprus was still recovering from the tragic events of 1974, everyone had to make do with what they had at hand.

We then move to the Russian classics section and costumes from the plays by Anton Chekhov. These plays are popular in Cyprus and many other countries in the world. The range of emotions in Chekhov’s plays is manifested in the choice of colors for the costumes. The «Three Sisters» dresses are black in color with only a small patch of white — a symbol of hope and faith that is intrinsic to the Russian people.

Going forward we come across «Mary Stuart» a tragedy by Friedrich Schiller (1759 – 1805) about the last days in the life of the Queen of Scotland.

Back in the 1970-80s local costume designers used to make everything «from scratch», starting with the shoes and all the way to the head garments. However, due to the financial difficulties that came with time, they were forced to sometimes purchase contemporary clothing items and accessories and then «adapt» them to the historical period of the play they were working on. This has led to many interesting creative decisions. If you study the costumes closely, fi you notice that they sometimes feature unexpected fabrics and materials. For example, the costume for the main character from «The Madwoman of Chaillot» — a satirical play by Hippolyte Jean Giraudoux (1882 – 1944), features a kaleidoscope of various materials (lace, beads, artificial flowers, etc.) together with theater fabrics that were dyed after the costume was created. Incidentally, unlike the finished costumes, their sketches reveal the names of their artists. So, for example, we come across the name Yiannis Toumazis (the stage and costume designer, who is the current Museum Chairman of the board and the Director of the Nicosia Municipal Arts Center), Telemakhos Cantos (the pioneer of «set designing» in Cyprus that he introduced in the 1940s), Marisa Haralampus and Elena Tsuri — young set designers, Nikis Loizos, a stage designer, and many others.

Some of the objects on display at the Museum have participated in temporary exhibitions at other museums and galleries.

We stop in front of the Menander comedies (324 – 291 BC), which have been staged as operettas in the style of the 19th – 20th centuries.

We move on to the «Medea» exhibition, dedicated to a tragedy by Euripedes. The play is part of a tetralogy, which includes Philoctetes, Dictys and the satyr play Theristai (all of which have since been lost). The demonic look of the princess and Jason’s lover is quite impressive thanks to the use of macramé and large feathers that accentuate the shaman nature of this wicked woman. THOC brought this play to the annual theater festival in Epidaurus (founded in 1954).

Like we said before, because of the difficulties that ensued from the occupation of the northern territories of Cyprus, the country struggled to support its theater industry. This is why many people in the profession had to be particularly creative and flexible to keep the work going. So, for example, all the people who worked on the production of the play for the festival had agreed to work for free. All the profits raised from ticket sales were used to help the Greek Cypriot refugees in the northern part of the island. Finally, the costumes were created by the Cypriot refugees themselves (many of whom spent years following the Turkish occupation inside refugee camps, one of which was located outside Larnaca).

Women made necklaces using old bottle caps, which they attached to the actors’ costumes as an imitation of gold coins. They also used empty bullet shells to make other types of original decorative pieces. The process came to symbolize the victory of life over death and the country’s journey towards peace.

Then in 1994 the play traveled to Greece, then to Russia (Moscow and St. Petersburg) and then to the US (New York), where the actors wore the same original costumes.

The upper floor houses a unique collection of archival materials and a library (containing 1700 volumes, most of which come from the private collection of N. Nikolaidis). Visitors are welcome to use the database for their research, seek any kind of help and information from the qualified staff or simply enjoy the view of the entire museum exhibition through the glass walls.

Please note that the study hall has five educational programs for children in kindergarten, elementary school, high school and university. The programs were designed to give a basic understanding of theater arts, to help develop creativity and imagination among the younger generation. Children are encouraged to work in pairs and small groups, rehearsing separate parts and doing other things.

During Christmas and New Year holidays the museum welcomes many famous actors, who come do readings for adults and children.

You can also book a group tour of the museum for your family or friends (the group has to include at least 5 people).

The exhibition will certainly be worth anyone’s time. Visitors are sure to love the breakdown of the scenes from «Don Juan» (the costume sketches include information about the fabrics and the description of the scenes from all of the five acts in the play). I was particularly fascinated by the colorful costumes from «The game of manners and cautiousness» by Yorgos Theotokas, which included gold leaf paper, tempera and other mixed media (designed by Yiannis Toumazis in 1992).

We conclude our visit with the following question: are you at all tempted to visit one of the Cyprus theaters and watch either a classical or a contemporary play there?

Address: Panos Solomonidis Street, 2-8, Limassol

Working hours: Monday, Wednesday, Thursday: 9:00 – 13:00; Tuesday and Friday: 9:00 – 13:00 and 16:00 – 19:00; Sunday: 10:00 – 14:00. Please call ahead of your visit.

Entrance: 3 euros (students and pensioners — 2 euros)

Telephone: +357 25343464

Email: theatre.museum@cytanet.com.cy

Website: www.cyprustheatremuseum.com

See you soon!

Written by: Evgeniya Kondakova-Theodorou.