The Museum was founded in 1937 by several members of the Society of Cypriot Studies (SCS) and is housed in the Old archbishop’s palace. Other museums, as well as the Pancyprian Gymnasium, the Cathedral of Saint Joan and of course, the current archdiocese, all exit onto Archbishop Kyprianos square. As a result, this not only forms an architectural ensemble and landmark for visiting pilgrims but a lively, developing historical-cultural space.

We were met by Eleni Christou, a Museum employee (also a representative of the Society of Cypriot Studies (SCS)), who kindly showed us through its halls.

How it all Began (a small excursion)

The Museum is housed in a 15th-century gothic building which has survived to the present day, with several constructive elements relating to an earlier age, since at the beginning of the 12th century, the Museum territory belonged to the Romans (the French). The monastery of the Order of the Benedictines was also situated on this land. In addition, the Order of Saint Joan erected a church here in honour of their heavenly patron. Hugo I was buried here in 1218, while the Greek Orthodox Church acquired it for a short time before the Ottoman reign (1571-1878). The richly decorated 16th-century gothic archway has a fresco displaying the Annunciation and displays the ending of an inscription in Greek, discovered in 1950. The fresco was conserved in 1955.

The palace of Archbishop Sylvester was later built between 1725-30 as a “second” floor (it resided here until 1960), but we shall discuss this a little later.

Many exhibits from the Museum collection have been donated, others have either been acquired or directly passed on from residents of Cypriot villages or owners of private collections.

The majority of items were produced in regions which are nowadays occupied by Turkish troops. Samples of weaving, pottery, embroidery, lacework, costumes, items of metal and leather, wood carvings, wicker and naive art — all of this, as well as various agricultural and artisanal (for instance, weaving) machines and instruments, is contained in this vast collection.

Today, the number of units preserved in the museum totals more than 5,000.

The old residence is located on the square named after Archbishop Kyprianos, who was hanged by the Turks in 1821, at the start of the Greek rebellion. This was done in the aim of suppressing the uprising in Cyprus, which along with inland Greece, was also under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. Kyprianos was seized from his own cell in the palace building and escorted to the place where he met his heroic end, thus becoming a martyr. Across the road lies the Pancyprian Gymnasium, the oldest and largest educational institution in Cyprus, which is a continuation of the Greek school founded by Archbishop Kyprianos in 1812, dedicated to the Holy Trinity.

The building was gifted to the Society by Archbishop Makarios III, the first President of the Republic of Cyprus. During the national anti-colonial movement in the years 1955-1959, the museum was thrice forced to close. In 1961, the archdiocese residence was moved to a different location (a new palace was erected from 1950-59 on the same square, at the intersection of Socratus and Adamantiou Korai street). The Society then approached His Beautitude with a request to provide their members with the former space, in order to use it for research and promotional work. In the period from 1962-64, large scale restoration work was performed, funded by the Society, with the support of His Beatitude Makarios III (as Diamantis A recollected in 1973).

In addition to the “turbulent 50s”, the collection was evacuated to a safe place in the summer of 1974, during the Turkish invasion, and the Museum was again closed for a year. However, the exhibits’ “adventures” didn’t end there. For several years, the museum employees themselves noted several alarming factors: part of the museum’s collection demanded extreme preservation measures; the building’s roofing was in а dilapidated state, and increased humidity was causing irreparable damage to the exhibits. Finally, in 1990, Archbishop Chrysotomos magnanimously offered to cover all expenses, resulting in extensive repair works taking place, which were completed in April 1996, when the new expo halls on the first floor were opened to the wider public.

In the Museum: Yesterday and Today

During our visit, a regular short-term exhibition was being held. It was dedicated to Kythrea “Threaten art of Chitri” (organised by — the SCS, the municipality of Kythrea, the Society of Friends of the folk art Museum and volunteering enthusiasts; a catalogue was published), and marked the start of our acquaintance with the Museum. While ascending the stairs to the second floor, outside you will see fragments of a water mill mechanism and devices for silk production (a vat for brewing silkworm cocoons and a “drum” for further spooling the obtained threads. Silk, as we already know, was produced across the whole island and differed everywhere. The centres were: Morphou, Paphos and Kythrea, where “yellow silk” was manufactured; wooden gates, Venetian lions carved into stone, as well as other pieces of evidence from the past.

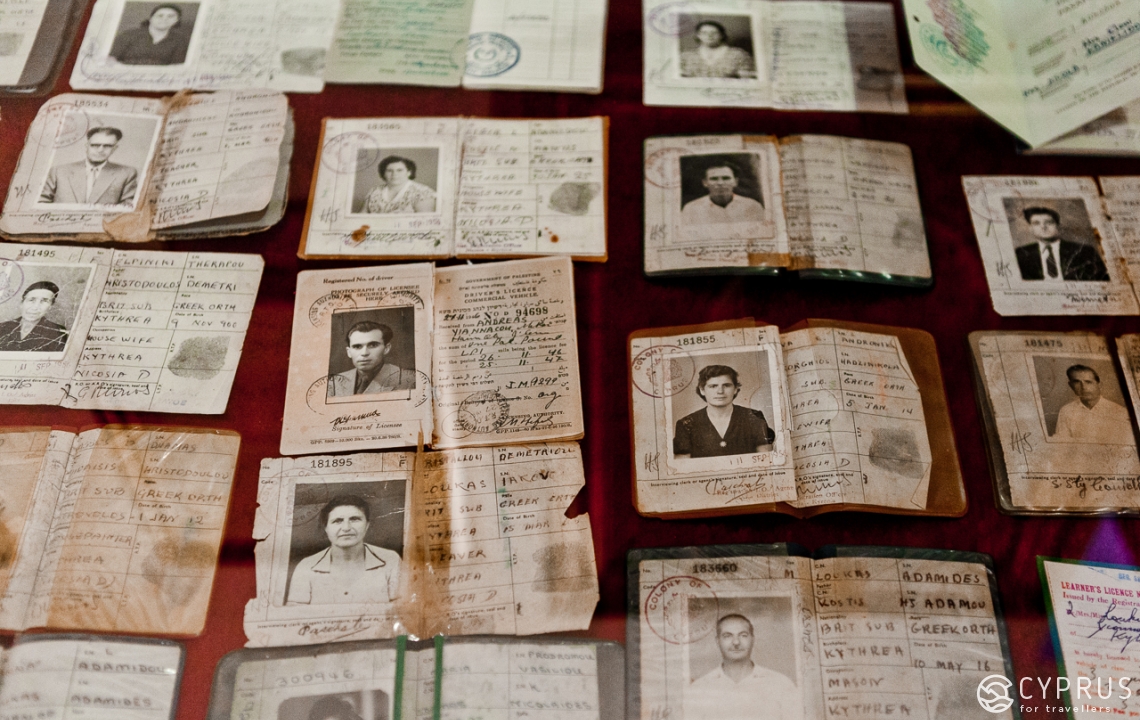

And so, the exhibition which we visited occupied several halls and gave an account of the region and the people of Kythrea. In ancient times, the kingdom of Chytroi was situated here, while in the recent past, the population had to endure the invasion of Turkish aggressors and were forced to abandon their homes and lands, escaping to Nicosia and its districts. It’s not surprising that the first hall is dedicated to refugees: documents, school tokens and badges, photographs of bygone years… and even keys to abandoned houses, where people had hoped to soon return. The exhibition isn’t without its “note” of English culture: mannequins are dressed in the military uniform of the British airport from those years. There are also echoes of the Second World War: personal identification documents and elements of military uniform from those Cypriots who fought in the war on the side of the British (in total, 30,000 troops were in the allied ranks of the anti-Hitler coalition: Turks, Greeks and Armenians). Incidentally, the mobilisation of troops on the island was announced in September 1939 by Governor W. Battershill.

Eleni recounts: “This exhibition was held thanks to the participation of many Kythrean natives. Can you see the old photo of an elderly lady? We didn’t know who she was and weren’t able to identify her. One day, one of the visitors stopped opposite and in a stupor said: “Why that’s my grandma!” You can imagine the emotions people experience when coming here!”

We then found ourselves in the hall of ancient artefacts from the Chytroi region, which has been famous since ancient times: The ruler — Chytros, was the son of Akamas (and the grandson of Theseus and Ariadne, according to legend), who founded the city-kingdom here. A mass of unique archaeological items has been preserved which confirm this kingdom’s significance in ancient times. Numerous excavations were carried out from 1962-1974, some of which are actually on display in several cases; craters and other samples of ancient ceramics and sculpting. In general, the exhibits here envelop a grandiose period: from the Chalcolithic age right up to the start of the Medieval era.

Eleni states: “After the occupation of the North by the Turks in 1974, we fear that over the past years, all the artefacts left in digs and in the course of unfinished investigations have been looted and probably exported en masse to be sold at international auctions”.

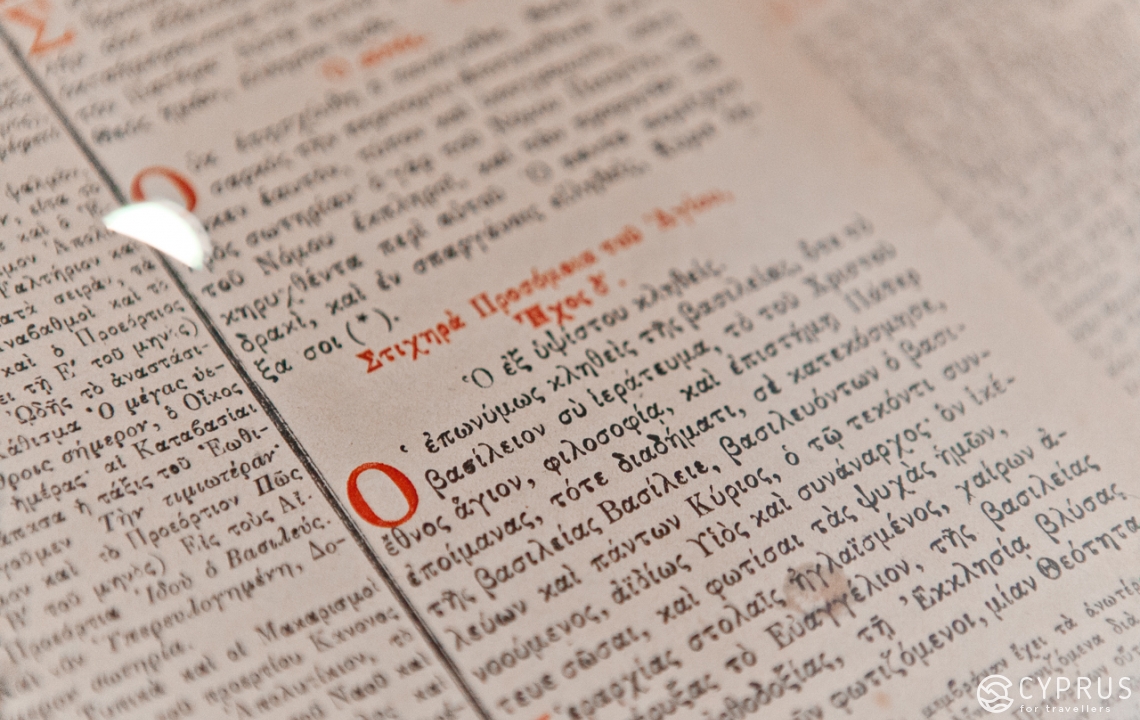

So, the next hall is dedicated to Medieval Byzantine art (icons) and other cult items removed from local places of worship for preservation. Here you can also see rare books, royal doors and carved chests.

The exhibits on display have originated from private collections, the collections of the Museum of Byzantine Art and the Folk Art Museum; some exhibits were also temporarily on display in several of Nicosia’s churches, which at one time received gifts from refugees in the form of sacred objects, removed from the abandoned temples of the once flourishing town.

Continuing the exhibition, we moved into the most spacious room, and the most interesting with regards to studying the everyday life of Kythrean residents: this life didn’t shy away from the luxury and fashion at its reach, which was primarily from the first half of the 20th century. There are many samples of traditional crafts (glass imagery, wood carvings etc) and handicrafts (embroidery, lacework) on stylish pieces of clothing, as well as refined local and imported (English) silver tableware, porcelain glass and various accessories. The “Barber’s Corner” is rather touching: there is a photo of Takis Sakaras — the barber himself, a man who could work miracles with beards and moustaches — lying in a small suitcase, along with his instruments — a small brush, sharp razors, scissors and combs.

Eleni, having noticed our interest, adds: “the Kythrean barber’s local “salon” was situated in a basement room of the municipality”.

The rest of the temporary exhibition halls feature the former chambers of archbishops, the reception hall and other rooms placed on permanent display as a memorial to the Palace.

A Permanent exhibition: in the Palace of Cypriot Archbishops

For this reason, having left the exhibition, we immediately found ourselves in a set of suites containing the gloomy chambers of the island’s higher clergy representatives: while passing further, we ascended (it can’t be said any differently) into the main reception hall: here, amongst other things, there were several archbishop thrones (two of them were gold plated, locally carved works, while the third was imported from the Napoleonic era, in an “ampere” style).

Eleni explains: “Meetings, conferences between Cypriot clergymen and receptions with foreign delegates would be held in this hall. Can you see the table with chairs? All of this furniture made a landmark in history: in the year 1950, behind this very table (with the assistance of the underground patriots' organisation EOKA) it was decided whether Cyprus would unify with Greece. A plebiscite was held (which, for justifiable reasons, was boycotted by the Turkish community) and 97.9% of the participating population voted for unification with Greece… but, of course, the British government of that time didn’t wish to hear the Cypriot majority’s declaration of intent. Interestingly, the collected signatures were represented by three lists: the first was passed to the Greek Parliament, the second to the British, while the third remained here, in the palace, “for Cyprus”. As such, behind this very table, the signatures for the “third list” were gathered. In addition, Archbishop Makarios III welcomed visitors to the residence here, right until 1960 when the new, neighbouring building, was erected. Note the fragments of a mural painting left on the walls (all of the walls in the palace rooms were covered with them). Nowadays, all this beauty is hidden behind a whitewash… it is intended to be uncovered in the future and restored to its former decorative appearance.

We also noted the carved wooden decorations on the walls (fragments), as well as portraits of Cypriot archbishops.

We were invited into the room of Archbishop Kiprianos (a national hero, famously executed by the Turks in 1821 and buried together with other martyred holy servants on Nicosia’s Faneromeni square).

Eleni continues: “… we also hold regular exhibitions in these rooms, For instance, a small exhibition recently took place dedicated to the 1922 Greek refugees from Asia Minor. We can see here things brought by settlers, as well as unique photos, — we decided to add this to the permanent exhibit, as with Kiprianos’ aid, it was in these walls specifically that the first higher education institution emerged in Cyprus: you can see items here reminiscent of its creation. The building opposite was later finished especially in order to house it”.

We pass to the end of this small room (which is, by the way, situated higher than the others, and in order to get here from the corridor, you need to climb several steps) where we can now look upon the pièce de résistance — the cloistered cell of Archbishop Kiprianos: on one of the walls resides a facsimile displaying all the deceased heroes of 1821, which has been compiled by researchers on one sheet of paper and placed under glass.

Having exited onto the second-floor wooden veranda, you have the opportunity to take a breath from the avalanche of emotions you have experienced, while looking at a small yet picturesque front garden and a square opening out behind it: history before your very eyes!

Through the branching of spacious corridors, also full of folk craft pieces (primarily wood carvings), we pass into a remote wing — a part dedicated to the era and activity of Makarios III. It contains his study, a library (now a book collection belonging to the SCS); a room of curious items (gifts from foreign guests and delegates, by and large from the “Eastern” collection of former President Clerides). There are a conference and seminar hall next to it, which also held other cultural events.

On Makarios’ desk lies a plaster sculpture of his head and a bronze mould of his hand. Patroklos Stavrou, a writer and close associate (1933-2014), with whom the archbishop shared his study, was responsible in particular for further providing the museum with its main exhibits concerning Makarios, including what was retrieved from the ashes of the scorched palace (during the attempted state coup).

Under the Archways of the Medieval Monastery

Now we descend into a courtyard surrounded by ancient buildings (the cathedral of Saint Joan, the building of the Archbishop Makarios III Cultural Foundation — a part of the archbishopric) and other constructions. We enter the first-floor main entrance. The cosy souvenir area (we were amazed by the unbelievably low prices for originals works of applied arts, filled with a wide range of taste and expertise) and the book stand (where, incidentally, you can find catalogues and yearly almanacks — a collection of scientific articles studying Society folklore, which began being issued in 1936) won’t affect your impression as you first enter. This is a monastery complex with an enfilade of stone halls lying under tall archways (the inner church is immediately evident once having entered). On the right side lie several, practically window-less cell rooms (where the monks once resided). Passing through the old lancet arch featuring the Annunciation (on the left — the Archangel Gabriel, on the right — a figure of the Virgin Mary; the gothic rosetta above, which crowns the archway, was stricken out by the Turks and naturally, disappeared without trace for a long time) you will also see several ancient icons, including a two-sided icon of Saint Foma, as well as several church items (including wooden carvings). As such, you find yourself in the next hall, which features ancient ceramic ware (pots and other utensils from the 19th- early 20th century) and a medieval stone carving: the lions on the Lusignan coat of arms.

Did you know: the large clay pots on display weren’t manufactured on a potter’s wheel, but incrementally pasted together: one layer would dry a little and another would be added to it. Judging by the number of “rings”, you could even count how many days it had taken the potter to complete the piece… sometimes up to 70.

“Find the lion” — a museum game for children and adults alike, and a test of your observation skills: employees might offer you the chance to play. You need to find and count all the images of lions present in some form or other within the exhibition. Here’s a hint: the “lions” can be anywhere, while the correct number is only known to museum employees (we now also know, but we won’t reveal anything).

The next and most spacious hall also features a collection from the Jewellery museum of Nicos Ioannou — a famous Cypriot jeweller and owner of several boutiques (the display cases are along the windows to the left). As Eleni told us, in past years the Cyprus Jewellery Museum was situated on Onasgarou street (the Old City of Nicosia), the Folk Art Museum later gave Mr Ioannou the offer to house the collection in its own walls. The collection contains works of Cypriot artisans from bygone years, as well as private jewellery sets and silver tableware, gifted to the Museum by several families of jewellers. The display cases feature church trays (from the churches of St. Andrew’s monastery in Karpathia in the part of Cyprus occupied by Turkey; they were transferred to the Museum in 1954) crafted by the people as a token of gratitude for the great assistance the Church provided with their affairs. In fact, a similar museum existed approximately 5 years ago in Lefkara (I remember I was lucky enough at that time to visit its permanent exhibition in one of the “Italian” houses neighbouring the town hall, the first floor of which was occupied by the contemporary jewellery salon of N. Ioannou). Later, as we learnt today, — the full collection of the museum’s former exhibition halls was transferred here specifically, to Archbishop Kiprianos square.

Eleni adds: “…each exhibit, as you can see, has its own history and “chronicle”, while this small room at the end of our exhibition was actually designed as a workshop for a gold and silver craftsmen: jewellers’ instruments and workbenches have been installed, as well as samples of gold with varying purities”.

Opposite the “jewellery” display cases, you can see two very unusual yet symbolic exhibits: fragments from the wall of Kafenio (a region of Nicosia). Two famous characters, close to the heart of any Greek or Cypriot, are pictured on the walls; they have been drawn in the naive manner of a self-taught village artist.

Eleni: “Adamantios Diamantis, a famous avant-garde artist (1900-1994) who permanently held the position of Museum director, took them from Geri especially for the Museum. One of them was the strongman Panaiotis Kutalyanos, a native to Greece with a Cypriot father. He toured all around the USA, Peru, the Balkan countries etc. To this day, rumour has it that his strength was so great, he could lift a steam engine! Naturally, the only thing this strong man feared, was his wife. Another character was a significant figure in Greek history and a hero of the 1821 Greek revolution — Athanasios Diakos. You see, this naive artist (he was a master of shadow theatre), with the means accessible to him, strived to transfer a human’s characteristic traits to the viewer: attention here was focused on his jet black hair and moustache, as well as… his unbelievably huge, strong chest — a sign of heroic nature and a symbol of resilience. He was executed in a terrible manner: the Turks essentially impaled him on a metal stake”.

At the very end of the hall, surrounded by samples of wooden carvings (decorated and carved jambs, cornices, chests etc), there are other samples of naive art: the work of And. Stilianou “Lapithos” (a locality in the occupied North, famous for its ceramics; the most famous master in Lapithos’ history was the potter Aristophanus). M. Kashalos’ picturesque work — “the Wedding” represents an alignment of numerous details from a village wedding ceremony, nowadays portraying a frightening impression of life’s severity and the strictness of its customs in the past.

Eleni says: “The artist, a shoemaker “by vocation”, doesn’t simply build a composition, but on the contrary, strives to insert as many domestic details as possible. On the bright side, today we have the opportunity to observe those past mutual relationships and the hierarchy accepted in society… Here is a bride and groom after their wedding: the young spouses (14-16 years old, which was often the case) bashfully touch one another with their little fingers. Or here — the scene of a bride being accepted into the family by her mother in law: the old woman blesses the young girl with a new family life; while the bride attempts to win her favour by symbolic means. It would seem that times and morals may change, but people and relationships stay the same.

We pass further from hall to hall (the monks’ former chambers), where clothes items from different regions (for instance, the widely popular traditional female dress “amalia”) and samples of all kinds of handmade wares and crafts are on display. Furniture items and familiar utensils from other Cypriot ethnographic collections are available for public interaction; here you can see dried bottle gourds, which served the potters of ancient times as prototypes for future products; these weren’t mundane items, but featured skilful carvings with images of mermaids, flowers and snakes.

The Moral of The Story: You cannot have a monastery without a secret passage…

Our guide, having finished her story and our excursion around the halls, suddenly stopped by a low-lying door, just the right height for the Rabbit from Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland”: it was literally at knee level. Eleni invited us to peer into the hall right behind the door. Puzzled, we knelt down and opened it a little: behind it there turned out to be a rather small room, but big enough to stand in at full height — a forge! There was an anvil, fur skins, a hammer and pincers — everything it seemed was fully in its place, as tradition would have it. We assumed that all the surprises for the day had finished, but we were wrong: Eleni, pointing to the depths of the tiny box room, said something which resulted in us being troubled for a long time afterwards: “and this is the entrance to an ancient tunnel. To this day, we still don’t know where it leads to, or what lies there”. We were promised that work would begin on researching it as soon as the Department of Antiquities gave the go ahead. When that will be, however, is yet unknown.

As we said our byes for the day to our amazing companion, Eleni Christou, we again stopped by one of the collection’s genuine masterpieces (in the Museum foyer): the doors to the Church of Saint Mamas (19th century), featuring a carved figure of a wooden owl, which particularly inspired the Nobel laureate and poet, George Seferis (1900-1971), whose poem “Cyprus Trivia” was dedicated to Adamantios Diamantis. The owl, which particularly appealed to the poet, is the outer part of the door’s bolt, “perched” upon the keyhole: if you pressed on it, the door leaf opened from the other side, allowing you to enter the building. Upon exit, the door would simply slam shut.

Address: Archbishop Kyprianos Square, Old City

Opening Hours: Tuesday- Friday: 9:30-16:00, Saturdays: 10:00-13:00

Closed on Mondays and Sundays

Entry: 2 Euro (Adults), 1 Euro (Students)

Telephone: +357 22432578

For more information, visit: www.cypriotstudies.org

Until next time!