Bread is life — a deep truth that has been ingrained in all of us from birth for millennia. It’s been officially posited that crop farming as a branch of agriculture appeared in Mesopotamia and the Levant over 9 thousand years ago. Humankind discovered and has been developing its wheat cultivation skills since then.

Bread is a staple food the world over. Ancient fertility cults in the agricultural practices of early civilizations were primarily aimed at encouraging a sufficient harvest of wheat in order to survive and then pass on the gift of life to the next generations ...

Read our article today to find out more about modern-day Cypriot baking: we’ll look at the latest technologies but also cast a loving eye over past traditions and, probably, even reveal some secrets ...

It seemed we’d been lucky enough to literally «learn it all»…

... after being invited to visit Mitsides, a company with an 85-year history. It is currently the leading bread and pasta producer in Cyprus and also works in technological research and development [1].

Baking traditions are one of Cyprus’ ancient treasures. This can easily be seen by perusing the assortment of local bakeries and pastry shops, visiting ancient mills (water, wind, etc.), and walking around the Museum of Bread in Limassol. Learn more by reading our culinary crash course and watching a video (in Cypriot Greek) here.

Whole villages, like Athienou and others, have long been hailed for the skills of their bakers with their recipes that are still followed today, and the efforts of their grain farmers who have cultivated the land for centuries and produced a tasty and nutritious wheat. Incidentally, the wheat grown on the island, like barley, one of Cyprus’ staple crops [2].

-

Wheat was one of the first crops to be grown on a large scale back in the early days of civilization; it is also one of the key factors behind the rise of urban communities. Archaeologists believe that the tradition of its cultivation and subsequent processing into edible cereals started out in the Middle East.

Historians believe it was discovered that flour can ground from wheat grains using stones around 9000 BC.

So we all know bread rolls don’t grow on the trees but they are such a familiar, every-day food. So, how did it all begin? It turns out we kind of take it for granted, don’t you think?

Wheat should be harvested when the ears of ripened grains start to weight down the stems bending them towards the ground. The harvested grains are separated from the stems and chaff. They are then husked, i.e. the outer casing of the seed is removed so they can be ground into flour.

There are a lot of wheat varieties all over the world. They can be classified according to growing season, colour, and content and quality of the protein. There are several classifications of wheat flour depending on what part of the seed is used and how dense its endosperm is (the tissue that provides nutrition for the seed embryo). In general, the harder the grain, the higher its protein content.

There are 3 main types of wheat (which we will discuss in this article):

- Wild Emmer (or Triticum turgidum) — has an oval-shaped grain with a powdery structure and long spikes on the ear. Its flour is high in protein (gluten) and is used for baking bread and cake bases, as well as fresh pasta.

- Durum (from the Latin: Triticum durum), is the variety traditionally grown in Cyprus and in a number of other regions of the world. It has the hardest grain of all varieties and is rich in gluten. It is considered to be the most ancient variety and was cultivated in the Neolithic Age. In addition to its high protein content, its gluten is inelastic, which makes this variety ideal for semolina and premium pasta.

- Common wheat (Latin: Triticum vulgare) — a soft, low-in-protein grain. These varieties are the most common worldwide.

It is believed that these varieties first grew in what is now modern-day Afghanistan. Its flour is lighter (because its starchy grains) and it is used to make cookies, breakfast cereals, crackers, etc.

All clear so far? Unfortunately, there’s a «but»:

Over the centuries, farmers and cultivators discovered that wheat can gradually change under the influence of changing environmental conditions. This was how the hard varieties were gradually transformed into soft ones.

That’s the hardest part out of the way, onto something simpler: flour production. It is made by crushing cereals such as wheat, rye, barley, corn, etc. It is the main ingredient in most types of bread and other baked goods across many cultures. It is the leading source of vegetable protein in human food and an excellent source of complex carbohydrates and dietary fibre. It is also rich in B vitamins, carbohydrates and elements and minerals the human body needs (phosphorus, calcium, iron, magnesium and potassium).

So, how do they produce flour and bread today in Cyprus? And what criteria are used to select certain wheat types for different products?

The wheat processing procedure starts off with preliminary testing. If samples pass all the tests, the grain is sorted and immediately sent for unloading.

The best wheat varieties are selected for each specific product. Mitsides is a market leader and uses the latest quality control technologies, which meet all modern standards. The company has built up a recognisable brand and sells 40% and 50% of pasta and flour respectively on the local market. What’s more, Mitsides are successfully breaking into the markets abroad and earning international recognition.

They have committed to retaining the knowledge of their forefathers and have a lot of respect for and wisdom to share about the former bread-baking traditions on the island.

At the Mitsides Group Plant

Our first visit to Mitsides took place in its old location in the Old Town, Nicosia, at: Nikiforos Fokas Avenue 34-38.

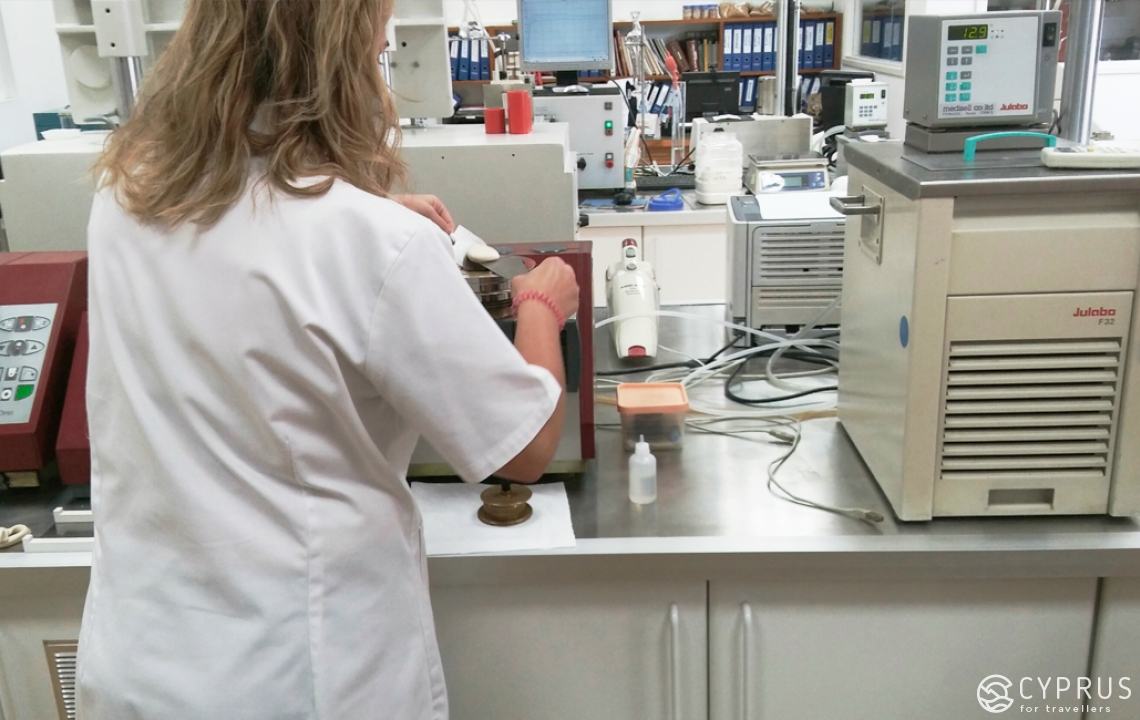

We visited the process control department in the old mill building. We were warmly welcomed upon arrival by the company’s process engineer.

We were told that the Quality Control Department oversees strict quality control across the entire process and at all stages of production: from selecting the raw materials to the distribution of the goods produced. Mitsides has the following food safety certificates: 22000: 2005 ISO (HACCP) and ISO 9001: 2008.

The laboratory is managed by a team of highly-qualified staff: a process engineer, chemist, and flour milling engineer.

The laboratory of 100 experiments

The samples of grain, flour and finished products undergo daily quality control tests employing up-to-date technology to ensure high quality standards for all their branded products. We were told that after being cleaned and washed in water, the wheat is also specially processed and thus can no longer be called a raw material.

What’s more, Mitsides recently built a fully-equipped bakery workshop next to the laboratory where each batch of flour produced can be tested for quality and «bakeability» in real, almost control conditions. This ensures all flour products are of a high quality.

We also learned a cute fact: the company’s specialists not only conduct hundreds of experiments every month but also occasionally try to bake something using the flours obtained in order to see what needs to be tweaked and improved: both in the recipe stage and the raw material selection phase.

Well, it seemed we’d come to the right place: we saw how everything was made and even got a chance to take measurements with the specialists during the experiment phase.

One of the specialist's fold us, «Before we send the main batch of wheat to be ground, and then send flour to market or to the production line, samples are brought here to be studied and checked for compliance with standards.

The wheat's consistency is checked in a wet state: we let the grain soak up as much moisture as possible.

Our goal is then to separate the bran from the grain itself. We have special equipment designed for this very purpose. Our most basic piece of kit is a farinograph (from farina meaning flour). It measures the degree of water absorption by grain, which is key information for bakeries — our main customers!

We also study how the flour behaves when mixed with water. It’s very simple: a quantity of water is measured out according to the recipe for obtaining dough and mixed with flour in a mixer. Regarding the expected results: the amount of gluten in the flour means it can be sorted and given a particular grade. After all, each variety suits a certain type of food while not being suitable for others!

Then, when the mixing stage is complete, the dough is squeezed through a narrow hole, which forces it into a kind of ribbon and its elasticity is checked, i.e. how strong it is. For example, this flour is «strong», the dough sample it produced is good and, as you can see, it stretches. However, there are some subtleties to look out for. If, for example, this flour is mixed for longer than 15 minutes, the gluten will be activated and work more actively resulting in a dough that simply will not be able to rise well.

We produce 3-4 kinds of wheat flour every day at our milling site. The staff collect it and put it in sacks with different markings and send it here. We test standard wheat and flour of the varieties mentioned about as well as others. If necessary, they are sent to us by our clients for study. For each type, we have our a tried and tested recipe: for making cookies, for pizza, etc.

What’s more, the quality of the harvest has an impact on the test samples. For example, this year the harvest was quite weak to be honest.

There are a lot of chemical processes that go into producing flour for the baking industry. Nowadays, our customers are very demanding: they produce a huge range of products so it’s vital that everyone gets the «right» recipe and the «right» flour for each product. What’s more, we have a lot of customers so we have a huge warehouse. Sometimes, lorries arrive 20 times a day.

Talking of varieties: there were once attempts to try and select varieties of wheat grown in Cyprus to obtain a more delicate taste and airy crust. This is the dilemma: we want to maintain traditions but have to take into account that tastes have changed a lot!

Here is another piece of kit — a stress resistance meter. We let the dough sample rise for 4-5 minutes, mould it onto a special piece of equipment and then stretch it to determine its level of «resistance» to being handled and kneaded.

Over here, we can do an express test of our dough and its properties. We take the first sample of flour, mix it with water for 28 minutes, then take 5 small pieces of dough and let them rise at 25C. After that, we slowly inflate it from the inside for 15 minutes to make the dough into a kind of ball. When it bursts, we can collect the data and record its properties.

If the flour is very expandable and increases in volume easily, it means it is good at taking on a certain shape. Sometimes we need a type of flour to be very elastic, because it means that the dough will return to its original shape easily. The type is only suitable for biscuits, not pies or cake».

Did you know?

1. What is the difference between flour for baking cakes and flour for making bread?

You need yeast to make bread dough, right? Therefore, the other ingredients for your dough should be «strong» (able to maintain the shape of the loaf or rolls produced), and have a high protein content. This isn’t the case for sweet baked goods. For example, if you want to bake a cake at home, you should use plain, soft, or self-raising flour that comes in red, brown, and blue packaging respectively. You should avoid strong (orange packaging) and others, which are to be used to bake rustic bread and other traditional recipes.

2. Why does flour come in different colours?

The travellers among us, or those who have participated in folk festivals in Cyprus at least once or even managed to experience local agrotourism, visiting farms and taking part in cooking traditional dishes, have probably noticed: flour seems to come in different colours in different countries or regions. Flour can vary in shade and tone from what you’re used to.

For example, traditional Cypriot bread, which mostly made for tourists or cultural holidays, is very dense and not very airy. Did you know that flour from domestic wheat differs from imported due to its rich yellow colour? The deeper and darker the shade of the flour, the higher its gluten content. Traditionally, Cypriot bread has a very high content.

3. These days, Cypriot flour is always a blend

Modern Cypriot bakeries, large and small, mainly use imported varieties (from Russia and European countries), and mix local Cypriot flour with these varieties. Despite being used for a long time in the local manufacture of baked goods, Cypriot flour doesn’t meet modern industry requirements.

For example, as we saw in the laboratory, it has quite a low elasticity, so it cannot produce an airy dough, which is necessary in many well-known and popular recipes. Of course, Cyprus wants to maintain traditions and ancient recipes but needs to mass produce products. Therefore they now only use blends in order to maintain consistency and appeal to the taste of modern buyers. Even the famous Athens bread is also baked using a blend of Cypriot and imported flour.

-

So, impressed with our newfound knowledge about the methods and technologies used to select and study the raw materials, we said goodbye to the laboratory ...

We were led directly to the Mitsides mill and production site near the village of Dhali, where its director and keen enthusiast and maintainer of family tradition and dynasty, Mr. Dinos Mitsides, was waiting for us (the company’s production site and warehouses are in the Dhali Industrial Zone at Tefkrou Anthia 16).

As you enter the office building and climb up the stairs, there are photographs that show the history and development of the flour industry in Cyprus. You can see the legacy in the faces of those who have worked for this one family business over the years.

We learned a lot from our tour with the director.

«Historically, the Mesaoria was the main area that Cypriot wheat was cultivated. Today, a significant part of it is in the occupied territory. Since 1974, some of our farmers have been forced to cultivate new areas under the fields after fleeing the area.

For example, one of Cyprus’ modern breadbaskets is the Paphos region as well as a hectare near Larnaca and the villages near the airport. We are unfortunately rather limited in terms of arable land.

On the other hand, as you already know, local wheat varieties don’t currently meet standards in full, so we use only blends in our production. Our blends only contain 10% Cypriot wheat, with the remaining 90% coming from abroad: France, Russia and Bulgaria.

Just like in the olden days, the weather conditions from year to year play a huge role: for example, about 3 years ago we had a great harvest — it was one of our most successful years. We harvested 20 thousand cubic tons of grain!

We don’t know what will happen in 2018, but our specialist are predicting a maximum of 3-4 thousand cubic tons. What a big difference!»

During our meeting, we were given pamphlets with catalogues and generously treated to a variety of pastries produced by the company.

We asked the director to tell us a little more about how Cyprus’ main flour milling, pasta and bakery production [3] got started. Here’s what we learned:

How Mitsides started…

«The story of how our family business got off the ground is a good one: my grandfather and his brother had previously worked as wood sellers. They transported wood on their own small boat,» continued Mr. Mitsides.

«One day in 1932, an event shook the family: their friends, who had their own mill, suddenly went bankrupt. Both brothers were their guarantors and during the trial conducted by the British authorities, they were told that as guarantors, they had to repay the bankruptcy debts. The brothers sold their boat to cover the debt, expenses and legal costs. However, they now owned the mills.

So, it turned out that they had a new path to follow despite everything that had occurred and the Mitsides brothers went into the flour industry. Their newly established business was a partnership called «Chrysostomos and Costas Mitsides» and it was clear it was in desperate need of serious renovation and a few injections of capital: the mills were old (in Old Nicosia). Flour had been ground there just as in ancient times using millstones [4].

They added a small pasta production (with a different name, in fact named after the former owner, Krinos), as well as an ice factory.

Back then, pasta was made like this: the prepared dough was shaped into spaghetti or other pasta shapes and hung on several hangers and carried outside to dry in the sun.

We paused this practice during the Second World War and only continued to manufacture Mitsides pasta in 1962. However, we then took a more technological approach and used imported machines from Italy.

As for the flour production industry, the company finally bought modern German machinery in 1955 that met the standards of the day and we were able to abandon the use of stone millstones.

Unfortunately, in September 1970, the plant was completely destroyed in a fire. The flour mill was rebuilt again on the same site, right where you were earlier: opposite the Famagusta Gate.

In 2001, our company bought another mill in Larnaca, which was the largest in the Cypriot market at that time. Our assets currently stand at: 2 flour mills, a pasta factory and foreign sites. For example, in Serbia, we have two mills at Mitsides Point D.o.o. as well as two pasta factories (Pasta Factory and Fresh Pasta Factory) and several bakeries.

Within Cyprus, we also supply a number of confectioners and bakeries with our flour and are the largest market player. Those 1kg packs you see on the shelves are only 5% of what we produce in total. I advise the enthusiastic cooks in your readership to buy our Farina (packaged in red). The flour we produce under this branding is a high quality product that will give your baked goods the edge — they’ll be light and airy!

The rest of what we produce (flour packaged in 25kg bags) goes to bakeries, confectionery factories and restaurants. We also export a great deal: 20% of our total product is exported with most going to Pizza Hut restaurants.

Mitsides has been the supplier to the pizza chain in the Middle East and the countries of the Arabian Gulf for 20 years now. Our company also has deals to export products to Bangladesh, Kuwait, Pakistan.

We are very proud of the many awards and prizes we’ve won. Take a look up on that shelf — there they are. The head office of Pizza Hut in Dallas gave us an award in a special ceremony!»

What do you think about discussing pasta, which is super-popular in Cyprus?

It is thought that the earliest recorded existence of pasta dates back to the 1st millennium BC (the Ancient Greek civilization). The Greeks used the word, Laganon, which meant «a wide, flat bread made from dough, cut into strips». They brought the recipe with them when they colonised the coastal areas of modern-day Italy in the 8th century BC. It’s thought that the Italian word «lasagna» that we all use today stems from «laganum» in Latin, which went on to naturally change over the centuries.

The same word is also mentioned in works by the Latin writers such as Cicero and Horace, as well as Marcus Gabius Apicius, the most famous gourmet of his time, who wrote of festivals and holidays that served Laganum in one of his first set of cookbooks called De re coqulinaria.

Mr. Mitsides continued: «In fact, the history of the pasta is really rather long and complicated — full of myths and contradictory information.

It’s not only traditional pastas recipes that use durum wheat but some modern ones too. If you use soft varieties to make pasta, the pasta will simply disintegrate when cooked and lose its shape and stick together».

…There’s no such thing as too many legends

Let’s settle down to read a few. As the director told us, there is an interesting story about how pasta spread throughout Europe [5].

Long, long ago, there was once an Italian sailor who sailed to China (as you know, pasta was also popular in ancient China and in Eastern Arabia), where he met and fell in love with a Chinese woman, the daughter of a bakery owner. He would visit her when he was on one of his voyages. One day they started kissing right next to the vat used to mix the dough in the bakery’s kitchen and the dough started to rapidly expand and rise.

The girl was terrified: if my father comes back to check on this dough and sees us together, he’ll kill us! The resourceful sailor, who legend has it, was called Emilio Spaghetti, grabbed a piece of the overflowing dough to stop the stern father from coming in to check. He ended up taking it with him to his ship. That’s how Italy got its first taste of the wonder-food, pasta, which then spread to many other countries.

Another, more famous legend has it that pasta was brought to Europe by Marco Polo. It is widely believed that he brought pasta to Italy on his return from the Far East in the 13th century. However, this idea has been debunked.

We’ll let you in on a little secret: whatever the case may be, the Cypriots love and hold the more romantic version dear!

We learned that the countries of the Southern Mediterranean turn out to be the best region for growing wheat for pasta. Even in Italy, for example, the best quality pasta is produced in the south.

Barley (the second most common grain crop in Cyprus) is never used in Mitsides products. After all, it was traditionally only used to feed livestock. However, in the past Cypriot bakers sometimes mixed it into the dough to bake cheaper bread.

These days though, we are often told about the benefits and nutritional quality barley offers and it is found in many breakfast cereals, snacks and breads. However, manufacturers around the world are clearly hiding the main reason for taking such a clear interesting barley: they don’t have our health in mind (despite the benefits barley with its microelements, vitamins, plant fibres, and proteins can bring) but are mainly in the pursuit of profit. They are selling a diet product simply as a way to reduce the cost of production!

Mr. Mitsides told us that almost 100% of the barley harvested in Cyprus is used for feed for farm animals ... because Cypriot households still hold animals, including donkeys.

About organic produce…

Mitsides told us about organic products on the market, which are popular with those who want to follow a healthy lifestyle.

«So, these days organic pasta is very popular. You’ve probably heard of it. As you can’t produce organic and non-organic flour and pasta on the same premises for a number of reasons, you need to have separate sites.

We imported Italian products that taste great and have superb qualities. Strangely, almost all of it simply did not sell in Cyprus. Why not, you ask? To be honest, we don’t even know the reason ourselves! (Laughs) I think it’s because the local consumer base wasn’t used to it... they were apprehensive about the product.

After all, lots of people have already heard about organic products and seen them in the shops being sold at prices much higher than usual. So why overpay when you can buy your regular product for cheaper? Though, there wasn’t a dramatic difference in prices of the products we were selling. Compare the price of bulgur wheat, for example: the usual variety sells at 1.40 euros, while the organic is marketed at 1.75 euros».

Nevertheless, we discovered that there are more than a thousand private farms that work to produce organic goods in Cyprus. This amounts to 46,980 hectares and 3.6% of the total volume of cultivated agricultural land.

We also learned that when manufacturing trahana (ground wheat — durum, soaked in milk alum / fermented milk) in the past, they first made a substance which they hung out, like pasta, on the branches of trees to dry. However, the smell of milk attracted a lot snakes. They crawled into the trees and climbed the trunk and branches to get to the trahana.

Protected fields

I also asked if chemicals were used to treat crops and protect fields from pests and bacteria. It turned out that another, more advanced technique was used: twice a year, the plants were treated with hot air using special equipment.

Yes, chemicals were used in the past. Now they use a more efficient and environmentally friendly method involving generators that produce hot air. Gradually the temperature is raised to 55-60 °C, which kills off the adult insects as well as all the larvae. All in all, the treatment takes 48 hours.

South – North

In light of the unresolved political and economic situation between the two Cypriot communities, Mitsides does not purchase wheat for flour and other agricultural products from Turkish Cypriot producers.

It turns out the opposite is true: a lot of people from the north come to the Republic of Cyprus because of the range offered by local producers and buyers. These days, they are mostly interested in ingredients (flour, cereals) and semi-finished products for confectionery and bakeries, some of which are imported from Belgium. For them, it is cheaper and easier to buy here than work with orders and purchases via Turkey (the only country that recognises the existence of the so-called Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus).

-

We thanked the management and employees of the company for telling us their history and giving us such a warm welcome. At the end of our visit, they took us to a large warehouse housing different types of their baked goods.

After our fascinating tour we started to wonder: what about small businesses and private mills working in the same industry... What are the differences (well, except for the size and capital, of course): where, when and how are old traditions preserved in the modern world and market. Is there a place for them at all? What exactly do small-scale farms produce today?

To find the answers to the questions that arose from our philosophical pondering, we headed to a small, private flour mill on a farm in the village of Kato Moni...

So we already knew that traditional Cypriot bread was made ONLY from durum wheat (from the latin for «hard»). European bread, like the loaves found in the majority of Cypriot bakeries these days, is made of white or cream-coloured soft varieties of flour while Cypriot durum is yellow.

We headed out of town, leaving the noise and hubbub of modern-day life and made our way up into the hills. It seemed that we’d done more than just escape the sun-dried fields but also ended up somewhere untouched by the passage of time — a quiet little village world where people live and work in the same way as their ancestors. A rarity in this day and age it has to be said!

The country roads led us to Kato Moni and we stopped at the house of a local farmer, who mills the traditional Cypriot wheat grown in the area.

The trip to the village mill or the real traditions as seen by our own two eyes

We were shown how the farmers in some Cypriot villages grind their wheat into flour at one of the private mills owned by Savvas Hadjigiorki Mills or in Greek, Μγλοι Χατζηγιωρκη Savvas Hadjigiorki, which happens to be one of the oldest still in operation in Cyprus. It is over 70 years old as it was founded in 1945.

The owners are an elderly couple that have a milling machine under a lean-to, which seems to have served them for decades. Inside this semi-building, there’s a curious shop — it's a kind of improvised local history museum with workshops and warehouses: everything here is reminiscent of the days of Archbishop Makarios III (there is a print of his ceremonial portrait hanging in the corner). There are also portraits of Cypriot freedom fighters, including Kyriakou Matsis, posters dedicated to the 40th anniversary of the EOKA and all this is surrounded by old forks, hoes and other farm tools, as well as the old household utensils found in any rural Cypriot home.

It is interesting to note that this display of old historical artefacts isn’t even considered a «museum» by the villagers: traditionally Cyprus home-makers hung all utensils used on a daily basis on the walls.

Why, you might ask? Basically, the economical and pragmatic rural farmers valued this useful and practical space — nothing would stand idle, lie about, and certainly wouldn’t be left half-built.

There’s also a small shop where for many years the owners have sold the fruits of their labour and the harvest they have collected and processed: traditional flour, wheat (grains), various other cereals, chickpeas, bulgur, green lentils, fragrant dried herbs and spices, etc.

That day, we were able to watch the same process we’d seen at Mitsides but in a more artisanal way compared to the industrial process in the factory.

The owner showed us the ropes: he sieved a few kilograms of pre-prepared brown wheat flour (that had been cleaned and filtered of impurities and had its surface layer removed) into a funnel that led into the «Seddo Dioso» branded machine. The grain moves along a hidden trench and ends up on a conveyor belt that moves it upward to then fall into the mill mechanism to be ground.

The roar of the motor, which causes the metal housing to vigorously vibrate sends the flour down into the removable bag attached below.

The air was suddenly filled with a thick floury fog...

We stepped closer to take a look and discovered that this real freshly-milled village flour was very different from what we normally buy in the supermarkets across Cyprus. It had a different density, strong, unique flavour and, of course, was the colour of deep ochre!

The flour was then packed in 25-kilogram packs made of thick paper with the family business’ label and stored right there in the shop.

You can read more about this village and its long history here.

We were lucky enough to witness this daily miracle...

What else can we add to what we’ve already told you? Here’s some official information...

The Minister of Agriculture of the Republic of Cyprus recently announced that the island now has financial support from the European Union to grow and cultivate certain varieties. This cooperation is linked to climate change. The prices of the wheat varieties grown, we were told, are to be annually submitted for discussion by the head of the Association of Wheat Producers in Cyprus and will be calculated based on forecasts of the future harvest.

The Republic of Cyprus is currently cooperating with various countries, including Serbia. The Cyprus-Serbia Business Association was founded in 2006 under the

Cyprus Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Chrysostomos Marangos Bakeries Ltd and the Mitsides Public Company LTD are members working in bread and flour production.

The Association works closely with the public and private sectors and aims to promote and strengthen trade between Cyprus and Serbia. The Embassy of Serbia in Cyprus, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Tourism of the Republic of Cyprus and other government and private institutions provide support. The Association invites individuals as well as legal entities of Cypriot or Serbian origin that make a tangible or even outstanding contributions to the local business community to become members.

To round up our story for today:

Finding the right flour is vital and is even considered the key to baking success among those who work hard to create culinary treats and top-quality baked goods.

You can check out the Mitsides website to find out more about where, when, how much and how wheat flour is used in Cypriot cuisine and find recipes at www.mitsidesgroup.com, or by stopping by our website for some inspiration and checking out the culinary section.

That’s all for now! Stay tuned for our latest articles and we wish you happy travels!

[1] In total, about 160 people are employed throughout Cyprus by Mitsides across their various departments and sites.

[2] The agricultural sector of Cyprus aims to implement further reforms and stimulate the cultivation of different crops by way of an efficient, environmentally friendly, and rational use of resources.

More information can be found here.

[3] By the way, that’s not all they do: alongside pasta and flour, the company also sells grains, makes pasta sauces and other food products, and sells raw materials to the baking and confectionery industry.

[4] The ancient principle of using a hand-made millstone to grind grain into flour and shelling cereals was used right up to the early twentieth century. They hand carved from two round stones of solid rock (quartz sandstone) and on average had a diameter of around 40 to 60 cm.

The oldest type are manual mills (mealing stones and pestle and mortars). They were followed millstones drawn by domestic animals such as donkeys or mules. They were widely used throughout Cyprus. There are museums of everyday life in many villages and many of them are hosued in former mills.

[5] The first full recipe for pasta can be found in the cookbook by Martino da Como (written in the 15th century). Later, there’s a description of the «correct way» of making pasta found in the works of Bartolomeo Sacchi, who was known as Platina. He was also the head of the Vatican Library. His method teaches us that «pasta should be prepared for as long as it takes to recite the Lord’s Prayer three times».

Pasta is also mentioned in the writings of the poet and writer Giovanni Boccaccio (written in the 14th century). In one of the stories from his most famous collection of 100 novellas, The Decameron, he describes a wonderful, far-off place where people live on a mountain of grated parmesan that looms over the landscape. It turns out, they don’t really have anything to do except make and cook pasta all day ... which is pretty funny don’t you think?